New York Penn Station was plagued with problems before COVID-19. Is the pandemic the time to fix them?

NEW YORK — New York Penn Station didn’t need a pandemic to make it the least desirable transit hub for hundreds of thousands of people every day.

It deteriorated to that level decades ago, but this underground midtown Manhattan portal sits there, a shell of its former flawed-but-bustling pre-pandemic self. For some, it is the critical factor about whether to return to work as the region struggles to reopen while staving off a relentless virus.

Not-too-distant memories still haunt riders of tortured daily commutes enduring unsafe, stampeding crowds, regular uncertainty about making their train because of it and whether there would be delays or cancellations. Nobody is in a hurry to resume that slog.

The 110-year-old landmark, once a glorious welcome for workforces from all over the region, now shields a dizzying subterranean maze in the basement of Madison Square Garden where concourses connect three commuter railroads and six subway lines.

Once inside, the most physically fit will win out as wading through crowds is inevitable, running is customary, and options for people with disabilities are maddeningly minimal.

It was a cringeworthy experience before the coronavirus. Those feelings are amplified now as small, confined spaces are feeding grounds for this deadly contagion.

The pandemic, which has decreased the station’s foot traffic by 80%, could prove to be another excuse for prolonged neglect of North America’s busiest transportation hub.

Or, as some advocates argue, it could be an opportunity to take advantage of the lull and use this moment in history — as other major cities have before — to transform this derelict pit into a visionary hub that could stand the test of time, and perhaps the next pandemic.

After decades-long attempts to remake Penn Station, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said in May that now is the time to “accelerate the Penn Station project when ridership is low and when we need the jobs.”

The wheels were already in motion before the coronavirus struck the region.

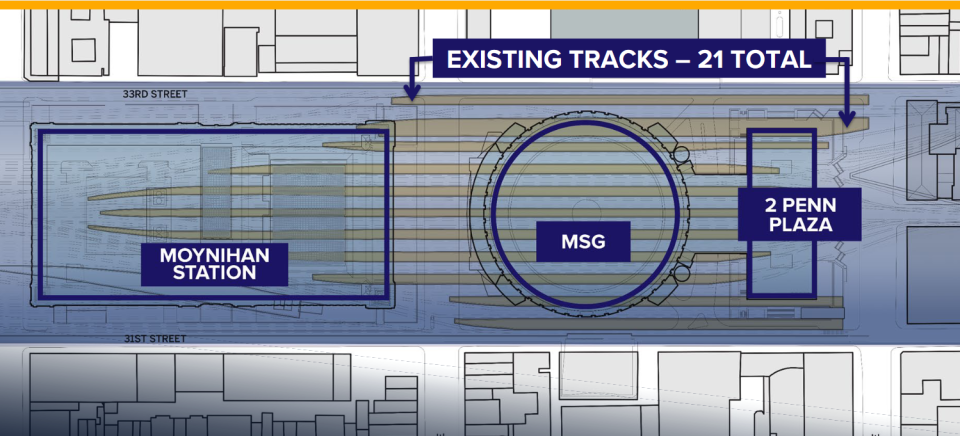

Before the end of the year, the nearby Moynihan Train Hall is expected to open and relieve congestion at Penn, offering additional access points to Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road trains. Cuomo also announced his plans in January for the Empire Station Complex that would expand the station’s underground rail network with eight additional tracks, create multiple new entrances and corridors and rehabilitate the existing Penn Station.

But customers, advocates and some transit experts say Cuomo's vision is more about commerce than commuters, and skirts Penn's most pressing problems.

They say Cuomo’s efforts fall short of fixing the chronic issues plaguing the station, do little to address new problems presented by the coronavirus, and favor business and real estate interests over those of rail improvements and the commuter experience by continuing to bury them under commercial square footage.

Greater attention, some said, should be given to moving Madison Square Garden, which comes with its own set of complications but could literally lift a tremendous burden off the constricted terminal.

“The transit use, the capacity uses are going to get larger, and this dance between the pillars of a sports arena and a train station just does not make any sense,” said Samuel Turvey, chairman of ReThink NYC, a coalition that developed its own plan for a new Penn Station.

“Frankly, our leadership needs to go back to the drawing board and think more, because they’re going to wake up 10 years after building this and people are going to be just as irritated and angry at what’s happened,"he said. "It's not going to work or be great. It’s going to continue to be awful.”

Meanwhile, the more than century-old Hudson River tunnels that connect to the station have begun to see more frequent failures, increasing the risk of a debilitating shutdown as efforts to fund repairs and build two new tunnels stall in Washington, D.C.

Now, however, could be the pivotal moment needed to change the future course for a station in need of transformation, according to those who say plans in the works fall well short of meeting the needs of the city’s busiest portal.

PENN STATION: STAMPEDES, SHOVING, SPRINTING

“Claustrophobic.”

“Disaster-waiting-to-happen.”

“Chaos.”

When pre-pandemic commuters were asked to sum up Penn Station in a word, those were the common answers. Now, they are the feelings and fears that weigh heavily into a choice they'll have to make sooner or later about returning to their Hudson River commutes.

Some former commuters who have stayed home for the last eight months are starting to wonder what the scene has been like recently at Penn Station.

Allison Blinder-Schneider asked commuting peers in a Facebook group about what awaited her on the NJ Transit Northeast Corridor line into New York City as she prepared to go back to the office.

“How is social distancing? Mask usage? Cleanliness, etc.?” she wrote July 29.

Trish Cisney, who also travels from Princeton Junction, responded that she noticed ridership was starting to pick up, but it’s been relatively smooth.

“I see everybody using their masks, people space out far enough on the train so we are not all sitting on top of each other,” Cisney responded.

The experience so many remember — and are now trying to avoid — is when thousands of riders would pack the waiting areas daily, wading through the masses to get to their gates during rush hour. Once there — if they made it before their train left — a small set of stairs or a single-file escalator funneled riders, like cattle into a pen, to the narrow boarding platforms in the dark depths of the station.

Add in routine delays or cancellations, and a pulsating crowd would quickly swell to suffocating dimensions in the waiting areas.

For some, the pre-coronavirus experience at Penn Station is enough to keep them from returning for the foreseeable future, especially now that many companies have accommodated work-from-home adjustments and have not planned reopening of city offices for some time while others contemplate shuttering them entirely.

Lindsey Stone said the station is one of the biggest reasons she is trying to get licensed in New Jersey to avoid New York Penn at all costs.

“I’ve been a real estate agent in NYC for 10 years and I’m terrified of commuting on the NJ Transit trains,” Stone said on Facebook. “I’m working to get licensed in NJ ASAP as I don’t feel comfortable running through Penn Station daily.”

People interviewed before the coronavirus told “Hunger Games”-like tales of launching into sprints when their gate number flashed on the screens, missing family time because of delayed, canceled or way-too-packed trains, and watching adults become physical to get to their destination.

Last winter, one man, who said he is originally from Yonkers and fled to catch his train before giving his name, described how the day before, he and another man had to blaze a path for a woman with a stroller.

“We literally had to hold people back so she could pick up the stroller with another person and walk down the steps,” he said, adding that if she had attempted to get down to the platform via elevator at that time, “it would be impossible … you have to go up and around, but she would never make the train.”

Then there is the safety factor.

Sixteen people were injured three years ago when a stampede formed in the station as people attempted to flee when police used a Taser on an unruly individual and those nearby thought they heard gunshots.

And while dangerous stampedes are still an anomaly at Penn Station, running through the station happens frequently.

At Penn Station, there’s no guarantee what track each scheduled train will arrive on each day, which is atypical for major train stations. This leads to a flash mob among commuters, especially during rush hour, when the track number appears on screens and hordes rush to the gate, sometimes at a full sprint because trains often depart minutes from the announcement.

“Riding the rails in Japan, for example, you know what your track number is going to be months, if not years, ahead of time, essentially,” said Brian Fritsch, who has studied and advocated for Penn Station renovations for the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit research group.

Penn's problem is partly because it’s a complicated system in which NJ Transit, Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road are operating at once, and even a minor delay on a train’s journey will change where it ends up in the terminal, said Jason Abrams, an Amtrak spokesman.

“We need to be able to identify in real time, as the trains are coming in, what track it's going to be on from our operation standpoint,” Abrams said. “Our dispatchers and our operations team, they monitor the tracks from everything from, you know, as far south as even Newark, monitoring all the trains that are going in and out of the station in real time on this incredibly complex system on the great, big video monitor board.”

Also, people can’t get on and off the train at the same time because of the small, limited platforms, stairs and escalators, which means gate numbers can't be flashed until the platform is cleared.

NJ Transit CEO and President Kevin Corbett is quick to point out that “we lost significant clout” almost three decades ago when the new off-site Penn Station command center opened. NJ Transit opted not to, or couldn’t, help pay for it, said Corbett, who took the helm at NJ Transit in 2018.

Corbett wants back in that room so NJ Transit will have a say in prioritizing trains coming through the tunnels and have the most up-to-date information about delays like station power outages.

BURSTING AT THE SEAMS

Today's Penn Station is a second-generation version that was built in the 1960s when its namesake railroad company was sliding into bankruptcy.

Strapped for cash, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the air rights above the station to businessman Irving Felt, who built the new Madison Square Garden there.

The original Penn that opened over 100 years ago was lauded as a hallowed space of civic-minded, elevating architecture and groundbreaking engineering feats before being torn down and partially buried in the nearby Meadowlands swamp in New Jersey.

When Penn Station shined

The tall, arched ceilings and open layout allowed sunlight to stream in from the rafters all the way down to track level. Its airy, almost celestial feel stands in stark contrast to the maze of low-ceiling, low-lit corridors that riders navigate through now.

The 1960s-era replacement terminal was designed for 200,000 daily train commuters.

By 1990, there were 215,000 riders coming in from Long Island Rail Road alone.

Pre-coronavirus numbers from this year had the station’s average daily foot traffic at 650,000, more than the number of people who go through the region’s three major airports combined on any given day.

NJ Transit experienced 226% growth since 1990, with nearly 200,000 weekday passengers coming through the station.

By comparison, LIRR had 225,000 daily passengers, and Amtrak, which owns the station and tunnels, had 22,000. Both have increased around 14% during those three decades.

Another 168,000 people travel through the station via six subway lines connected to the terminal.

Despite that substantial growth, the station hasn't grown one square foot.

In response to NJ Transit’s escalating ridership, Penn Station’s southeast corner was renovated in the early 2000s to remove some concession businesses to make way for ticket booths, a customer service area and the waiting concourse near gates to the tracks mostly used by New Jersey-bound trains. In 2009, the NJ Transit entrance at 31st Street and Seventh Avenue opened.

Over time, this southeast-area redesign became a victim of its own success.

It continues to be the primary hub for NJ Transit commuters, which Penn Station employees said leaves other gate entrances and waiting areas in the station underused — namely those on the Eighth Avenue side, which sees less foot traffic than Seventh Avenue.

Other smaller projects underway now in Penn Station include:

NJ Transit and Amtrak invested $7.2 million this year to renovate the “fishbowl” ticketed waiting area that includes new seating, tables and outlets.

Design work is underway to dismantle the display area in the NJ Transit pit to add more waiting space and bathrooms. The single escalator that leads to Tracks 7/8 in the NJ Transit concourse is also expected to be made into a stairwell to improve up-and-down flow.

The MTA is building a new entrance at 33rd Street and Seventh Avenue, where mostly Long Island Rail Road commuters convene.

Other renovations include a redesigned concourse that has higher ceilings, a wider waiting corridor, and more escalators and stairwells.

HOW TO FIX AN OVERCROWDED STATION

In addition to the small projects, there are a dizzying number of larger, but piecemeal plans to fix Penn and alleviate crowding. Some are still on drawing boards, some are in the works and one is nearing completion.

Moynihan coming to life

The furthest-along project is the long-awaited renovation of the Farley Post Office, which was built in 1913 across from Penn Station on Eighth Avenue. It is set to reopen before the end of the year and will be known as the Moynihan Train Hall.

The post office building, reminiscent of the original Penn Station because they were designed by the same firm, McKim, Mead & White, has platforms and access to most of the tracks in Penn. In its heyday, some trains that stopped at Penn had mail cars on the end that could be emptied at Farley while passengers deboarded at the terminal.

Ideas to bring the mostly defunct Farley building back to life have existed since 1993, but political obstacles slowed the process.

In 2017, a public-private partnership emerged between the Empire State Development Corp., the public agency leading the project, and a joint venture of private firms Vornado Realty Trust and Related Companies. Additional funds from Amtrak, the MTA, the state of New York and federal grants are helping to pay for the $1.6 billion overhaul to restore its natural-light ceilings and create a 225,000-square-foot concourse with high-end concession options and a wrap-around balcony.

Moynihan will primarily serve Amtrak and some Long Island Rail Road trains. With 40 additional escalators and stairs to platforms, this is estimated to relieve Penn Station’s traffic by about 20% and give NJ Transit more space to spread out in the original station, with access to more gates to tracks at Penn.

Some LIRR trains will also begin going to Grand Central Terminal in 2022 as part of the separate East Side Access program, but as early as 2024, some Metro-North trains are expected to end trips at Penn Station. Both commuter rail organizations are operated by the MTA.

Getting the Moynihan project off the ground is a "transformational" first step in improving the Penn Station experience, said MTA Chief Development Officer Janno Lieber.

“Spreading passenger loading out is a significant improvement from an operational standpoint, because you don't have to wait as long for trains to board. Also, from a safety standpoint, you've got a ton more [stairs and escalators] to get people on and off the platform," Lieber said.

After repeated requests to visit Moynihan and observe the renovation, the USA TODAY Network was told by the Empire State Development Corp. that it would not be possible because it could disrupt construction. Multiple local leaders, including Cuomo, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio and City Council Speaker Corey Johnson, were not made available for interviews to speak on the record for this story and did not respond to requests for comment.

While Moynihan’s opening will relieve some of the congestion in Penn Station, it does little to improve the commutes of NJ Transit riders. Its limitations are in part because Tracks 1 to 4, the ones used almost exclusively by NJ Transit, don’t stretch underneath to Moynihan.

More extensive Penn Station relief plans were in the works more than a decade ago that would have given NJ Transit access to Moynihan by extending Tracks 1 to 4 and lengthening boarding corridors in Moynihan and another in Penn Station.

These ideas existed in 2004 as part of early plans for the Access to the Region’s Core project. ARC was the precursor plan to Gateway to build new tunnels into Penn Station, but it was killed in 2010 by then-Gov. Chris Christie, who said it would put an unfair burden on New Jersey taxpayers and diverted the funds for state projects.

Plan to overhaul Penn Station

Ideas for more extensive renovations at Penn Station are being developed now by FXCollaborative Architects and WSP USA.

The New York-based firms were awarded the $9.5 million contract in January. It will be split by Amtrak, NJ Transit and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the agency managing the project. A public unveiling of those plans is expected “within the next few months,” an MTA spokesman said in October.

A public information request submitted to the MTA in January regarding the RFP and contract awarded to FXCollaborative has not yet been fulfilled.

NJ Transit hired FXCollaborative Architects separately in May to design a new concourse in Penn Station that would provide more access points to Tracks 1 to 6, which will be included in the master plan for Penn's renovation.

The plans will include ways to integrate the entire complex — including Moynihan and the Penn South expansion project below 31st Street — and ideas to improve passenger circulation, retail, visibility, safety and the overall experience. The details of how to accomplish this are not yet known.

Empire Station - Penn South expansion plan

Separately, Cuomo's Empire Station plan to expand Penn Station is in the draft phase. The proposed projects include condemning at least a block of buildings to add eight new tracks to the south of the current station, an underground corridor connecting the Herald Square subway lines and PATH trains to Penn Station, new subway entrances at nearby stations that connect to Penn, and an improved pedestrian plaza space around the station.

About 20 million square feet of space would be built for commercial, office, retail, hotel and parking garages in high-rise buildings constructed on eight sites along 31st, 32nd and 33rd streets on either side of Eighth and Seventh avenues. The revenue generated from these developments would fund improvements to Penn Station.

The southward expansion of Penn Station could be constructed by 2028, according to the report’s authors, FXCollaborative, the architecture firm hired by the MTA and Cuomo to lead this project. The full project, which was not given a price tag in the proposal, could be completed by 2038.

Lieber said the work at Moynihan, the new entrance at 33rd Street, Cuomo's Penn South expansion and the master plan are "interconnected, and they're kind of a step-by-step, how do we dramatically improve" the Penn Station experience.

‘LIPSTICK ON A PIG’

While concerned citizens, experts and commuters are happy to see the plight of Penn Station finally get renewed focus, the seemingly disparate plans don’t fully address the station’s problems, they said.

Fritsch, who has studied and advocated for Penn Station renovations for the Regional Plan Association, said that until major questions and concerns are addressed, the organization could not support the expansion project.

“In short, what does the public get in terms of public space and transit improvement from this proposal?” Fritsch said. “It’s hard to support a massive up-zoning complete with such a large influx of new people without understanding what the public benefits are going to be, knowing that Penn Station is such a difficult place for a variety of reasons already.”

Basic math suggests that Moynihan’s opening and Cuomo’s Penn South expansion would not relieve Penn Station’s foot traffic enough to meet its designed goal of 200,000, falling short by an estimated 145,000.

Though this calculation doesn’t take into account how the master plan renovation for the terminal would increase its capacity, it’s hard to imagine how these proposals would adequately relieve the preexisting congestion and account for future growth, experts say.

As for whether the proposals meet the capacity needs, Fritsch said: “The overall master plan for the station will hopefully kind of explain how they see people moving quickly and efficiently on or off their train to wherever they need to go. I think it’s still a little up in the air whether or not they’re able to figure something out that makes logical sense.”

Felicia Park-Rogers, of the Tri-State Transportation Campaign advocacy group, said the Empire Station plan was a good start but it's unclear how all the different planning pieces would fit together.

“One of the most impactful aspects of the pandemic is how it may change work, commuting and office patterns long into the future," Park-Rogers said. "This plan should reflect an emerging and changed reality without veering into costly and risky overdevelopment."

She said future proposals should address:

What evidence is there for increasing 20 million square feet of commercial office?

How does this support the expansion of platforms in Penn Station?

Can we know this without the master plan being in place?

Do the stairway improvements include any improvements in accessibility in the disabled or those with physical limitations with additional elevators and escalators?

Len Resto, president of the New Jersey Association of Railroad Passengers, said the Empire Station proposal falls short of improving the operational function of a train station, which should prioritize the commuter experience.

“Riders are willing to deal with the unpleasing aesthetics if only their trains ran on time, left from predictable track assignments and were clean. The escalator and stair enhancements proposed by the draft scope of work strike us as lipstick on a pig and continues the underground dysfunction that happens daily,” Resto said.

“It is distressing that the ESDC apparently sees this project as a commercial enterprise rather than as a significant part of the whole, including its most important component — transit.”

Fritsch said the 20 million square feet of commercial, office and retail space is warranted as long as it is “done the right way.” Plus, he added, much of the funding plan hinges on a model that relies on successful real estate to help pay for transit improvements. That private revenue would likely be essential, as the pandemic has aggravated states’ budget woes.

“There is a desire from firms to even now be right on the transit hub and have employees have an easy commute to and from work in the New York City region,” Fritsch said, noting that Facebook inked a lease in August for 730,000 square feet of office space in Moynihan. “Since most of the office space wouldn’t be coming online until 2038 … I think that’s a reasonable timeline” for the neighborhood’s real estate market to bounce back, he added.

WHAT DO WE DO WITH MADISON SQUARE GARDEN?

Among Penn's critics are those who have designed their own version of a reimagined New York Penn Station, ideas that would require major urban surgery: moving Madison Square Garden.

The 18,000-seat home of the New York Knicks and Rangers, which also hosts concerts and other events each year, was built on top of the train station in 1963. The location is ideal for shuttling thousands of fans and event-goers to an arena, but it physically restrains the function of a train station.

That's why the original Penn didn't include a hotel atop it when it opened on Nov. 27, 1910, Jill Jonnes said in her book "Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and Its Tunnels." Architect Charles McKim and his team said it wouldn’t work for his blueprint of the station that featured high ceilings and a skylit terminal.

Pennsylvania Railroad company executives also realized how detrimental large support columns would be for terminal space and future efficiency.

That logic faded in the decades that followed — when the concept of "air rights" emerged — and the idea was resurrected.

When Madison Square Garden moved for the fourth time in its history to the space above the newly reconstructed Penn Station in 1968, along with it came 260 support columns that go down to the platform level of the station, contributing to the inflexible, cramped boarding space.

Moving the arena, some say, would allow for a true resurrection of a great, civic-minded transportation hub.

Vishaan Chakrabarti, an architect and founder of the firm Practice for Architecture and Urbanism, said there are reasons and incentives for the Garden to move.

Among the reasons are that the loading dock now can’t accommodate unloading 18-wheeler trailers, so when concerts or events set up it’s more expensive and requires forklifts. Also, the arena has already moved four times.

“It's in both parties' interest to do it, because the Garden should have a great facility, right in the neighborhood, attached to mass transit, and the government should want a great station to tie to the capacity,” Chakrabarti said.

Chakrabarti proposed a design, which was featured in The New York Times in 2016, that would salvage the skeleton of MSG as part of a Penn Station gutting and reconstruction. His plan, which he estimates would cost around $1.5 billion, would strip the sides of MSG’s round structure to create a glassed-in pavilion, excavate the cavernous, 10-foot-ceiling concourses to allow sunlight to stream down to the track level, and remove the MSG support columns to make more space on the platforms for waiting, escalators and elevators.

“There's a new station hiding in plain sight,” he said. “You can recycle the existing foundation, the superstructure and the roof at the station, carve out all of the internal guts of the arena and leave the shell, peel off the skin, put a new skin on it that I show in my drawings as glass.”

The idea improves safety, Chakrabarti said, because his proposal includes a 150-foot ceiling that better ventilates the space if there is a fire — or perhaps an airborne virus — and expands travelers' line of vision. Now, he said, "it’s hard to find that exit sign. The architecture should tell you where to go."

Another plan — proposed by ReThinkNYC, a think tank with members including architects and transportation experts — would rebuild the original Penn Station, and it has three locations in mind to relocate MSG, though each comes with its own set of complications.

They are: Herald Square, the current site of the Port Authority Bus Terminal, or south of the terminal at Dyer Avenue and 38th Street.

The new station ReThink’s planners envision would be an almost exact replica of the original, which would restore the open-air space, natural sunlight to the station and a grandiose landmark that would restore pride to the city’s busiest hub, they said.

“There’s going to be a premium on healthier public spaces, healthier approaches to public transit — and the antithesis of that would be the present platforms at Penn Station,” said Turvey, ReThink’s chairman. “If we’re going to restore faith in New York City as a place to live and work, we have to get this right.”

But the functionality of the station would improve, they say, only if the whole network of trains between New Jersey and New York worked differently.

The group proposes eliminating some of Penn Station’s 21 tracks — a counterintuitive move for a station with capacity issues. But Jim Venturi, ReThink’s founder and principal designer, said this would dramatically improve station circulation, an idea contingent on its becoming a through-station so trains don't end there.

Taking out several tracks would make room to increase platforms so people could wait there for trains, which they can’t currently do, and would provide more space to construct additional stairs, escalators and elevators so people could board and disembark from trains at the same time, also not currently possible.

A through-station means trains would not terminate at Penn Station anymore. Instead, they would continue in the same direction to another station, rather than going in the reverse — more inefficient — direction, as many trains do now.

Allowing trains to continue through Penn Station avoids the wait time associated with trains crossing paths with others trying to get into or out of tunnels.

This eliminates the need for the Penn South expansion plan, Venturi said, and the money could fund through-running improvements to new stations in boroughs where businesses might be attracted to move if the transit options were there.

“You're really expanding the economic core of the city. Everything isn't so Manhattan-centric,” Turvey said. “Instead of making all the land in Manhattan valuable and more valuable and more valuable, and fewer and fewer people being able to live, work and enjoy, you all of a sudden make relevant many other places.”

However, Penn Station is already a partial through-station, because some NJ Transit trains continue without passengers during the day to sit in a rail yard in Sunnyside, Queens, LIRR trains continue past the station into the Hudson rail yard, and Amtrak trains continue north to Boston.

The MTA's Lieber said the rail agency is studying how to make the Penn South expansion a through-station system.

"You have different railroads that have different unions operating them, and different mechanical systems and different dispatching systems and a whole lot of very complicated different stuff," Lieber said. "No matter how much you focus on through-running, you know you need more tracks either way, and that's what this proposal is focused on.”

But ultimately, a resurrection of the original Penn Station, or recycling Madison Square Garden to breathe new life into the existing architecture, is contingent on a private company with a behemoth structure finding a new space in Manhattan.

The Madison Square Garden Co. has not publicly said it has any interest in moving, particularly since it completed a $1 billion renovation seven years ago. Abrams, the Amtrak spokesman, said the rail organization has not recently talked to MSG management or CEO James Dolan about relocating the arena.

A spokesman for The Madison Square Garden Co. wrote in an email: “We continue to partner with and support the Governor’s goal for a redeveloped Penn Station.”

The Garden’s owners were granted a 10-year operating permit extension by the New York City Council in 2013 that will expire in summer 2023 — an issue not addressed by any state or city official contacted, or attempted to be contacted, for this story. But Cuomo said in his January address announcing the Penn South expansion plans that moving the arena was not on the table.

“It's problematic to move Madison Square Garden. It's big, it's expensive, you have to find a place to put it; it's not that easy,” the New York governor said.

Cuomo said in January that he was in talks with MSG about acquiring the Hulu Theater attached to the Garden on the Eighth Avenue side of the arena to make way for a new, glass-paned entrance to Penn, but no updates have yet been provided on those discussions.

Richard Wilson Cameron, a ReThink board member and architectural lead, thinks moving Madison Square Garden to Herald Square could restore some of the arena’s original elements.

The key to selling it to the Dolans, he said, is it would “have to be more glamorous” than the current space.

“What was cool about the original Madison Square Garden is it had this whole roof garden — which is why it was called Madison Square Garden — and you could create a roof garden here on Herald Square with views of the Empire State Building, downtown, the river, and you could have a tower terminating 33rd Street,” Cameron said. “I just think there are astonishing architectural and urban opportunities out of this particular site.”

Fritsch, of the Regional Plan Association, said moving MSG should be considered in the plans being developed now.

“We would love to see the possibility of moving MSG being on the table as an alternative plan that is explored as part of this study,” Fritsch said. “I think it’s difficult to do it as it’s scoped now, but we think it’s a viable alternative that should get the same examination that is studied by ESD.”

DON'T FORGET GATEWAY

Power failures at Penn Station during rush hours remind the region and the riding public that the clock is ticking on the 110-year-old tunnels feeding trains into the station. Without extensive repairs to these Hudson River corridors ravaged by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, a tunnel may have to be shut down in the coming years to begin a years-long effort of repairs.

Absent substantial planning and river-crossing alternatives, this could be catastrophic for the region’s economy, which some estimate contributes 20% of the country’s GDP, and has already been hit hard by the pandemic.

A taste of this plausible reality hit in February when power issues debilitated evening commutes and left riders in a state of confusion and chaos at Penn Station for hours. The shutdown drove many to other Hudson crossing options that became overcrowded, and some customers were stranded on en-route trains, where there was one minor medical emergency reported.

In his address propping up the Penn South expansion plans, Cuomo said he was not waiting for the federal government “to decide they want to help New York or they want to fund Gateway.”

He continued: “We have to make our own future, and that is what we are going to do.”

Critics pushed back, arguing that the success of Penn Station and Cuomo’s expansion plans are contingent on fully functioning and ultimately expanded tunnels.

The Gateway program, $30 billion worth of projects including building two new Hudson River tunnels, rehabilitating the old ones, repairing several aging bridges and expanding Penn Station’s tracks, is largely in a holding pattern in Washington. The $11.6 billion tunnel projects portion has stalled as a deadline for the feds to complete the environmental review process passed more than two years ago, and applications requesting federal funding have collected dust.

While some say these are Trump-imposed delay tactics, his administration maintains that the projects are not yet eligible for forward movement.

New Jersey, New York, Amtrak and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey are prepared to pay for more than half of the project, but they are at the whim of the federal government and its dollars to move forward. A Biden presidency, however, could get the project moving.

In May, Amtrak chairman Tony Coscia said, "Amtrak, several years ago, began a very aggressive program of state of good repairs in order to try to minimize the amount of outages.”

But, he added, "It had been our company’s expectation that we would be building the Hudson River tunnel by now.”

Meanwhile, a revised financial plan submitted to the Federal Transit Administration in August estimated that costs of the tunnel elements of the project increased by $275 million in the last year alone.

'A SOCIETY THAT BUILT GREAT THINGS’

Easy to pass when rushing through Penn Station are rectangular mosaics that adorn the walls near the escalators at NJ Transit’s entrance at 31st Street and Seventh Avenue.

The artwork is a window into the past, depicting the original Penn Station. Its arching steel frames, open floor plan, Roman columns, glass ceilings and carriage entryway are historical reminders of a terminal unrecognizable for present-day commuters.

It’s a reminder of the decorum and majesty that once presided over a train station that now represents the antithesis of that.

“We were a society that built great things, and we said, ‘You know, there’s going to be massive disruption,’ and people put up with that, and we said, ‘We’re going to have dignity in our lives,’ ” architect Chakrabarti said in 2017 during an audience Q&A at the Museum of the City of New York.

But that has faded to an extent, he said, wondering what if the original Penn Station's creators didn't take people's commuting dignity into consideration when constructing that historic terminal.

"Let’s build the tunnels, let’s build the tracks but to hell with the station. Right? I mean, when did we get to a world where we have to make choices like that?" Chakrabarti asked. “This is because — and I know; I’ve worked in government — everyone is fighting over bread crumbs, and that’s what creates that mentality.”

In a more recent conversation, Chakrabarti, now the dean of the College of Environmental Design at the University of California Berkeley, continued this train of thought, saying today there needs to be more imagination when it comes to public spaces.

“These places are symbols of how much we care about ourselves,” he said. “We used to build these things because they were signifiers of what we felt our civic world should look like, our place in society — so I’m not willing to give up on that.”

The question that remains is how — or whether — Penn Station will return to greatness for its bustling commuter dwellers or simply those who want to stand in awe of an urban wonder in the middle of New York City.

Colleen Wilson covers the Port Authority and NJ Transit for NorthJersey.com. Email: cwilson2@gannettnj.com Twitter: @colleenallreds

The team behind this investigation

REPORTING AND ANALYSIS: Colleen Wilson and Peter D. Kramer

EDITING: Frank Scandale

PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO: Seth Harrison

NARRATION: Ryan Ross

MULTIMEDIA EDITOR: Carrie Yale

DIGITAL PRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT: Kyle Omphroy, Také Uda and Spencer Holladay

SOCIAL MEDIA, ENGAGEMENT AND PROMOTION: Candace Mitchell and Courtney Marabella

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: NY Penn Station: Is the COVID pandemic the time to fix its problems?

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies