‘He won’t leave me alone.’ She tried to leave the man she met at 13. Then she went missing.

When Angie González vanished from the small town of Barranquitas earlier this year, her mother began imagining Puerto Rico’s steep, verdant mountains.

Elba Santos flew from Connecticut, where she has lived since Hurricane María, to search for the 29-year-old nurse and mother of three in the Cordillera Central, the sierra that fractures the island in half from east to west.

For days, she drove through the winding roads from morning until night, stopping and shouting her first born’s name into the wild abyss below.

“Angie, please, if you are there, speak!” she cried. “I am looking for you, it’s mamita. Angie Noemi!”

It wasn’t like her daughter to leave without telling someone where she was going. And the timing of her disappearance was alarming. She’d just broken up with the father of her children, the man she’d been with for 16 years and who kept a close eye on her every move.

“I don’t want anyone to stop me,” she told her mom before going missing. “I don’t want anyone to call me in the morning to ask what I am up to, where I am, why am I taking so long. I want to have my own life.”

In recent years, Puerto Rico has been pummeled by hurricanes and earthquakes, leaving many homeless or living in unsafe housing while also struggling to make ends meet. For women experiencing abuse, leaving became even harder. Then came the pandemic. A strict quarantine kept women stuck indoors, with fewer opportunities to ask for help in a region where a reckoning over abuse against women has barely begun.

The official figures suggest women in Puerto Rico may have been safer during the lockdown. Domestic violence incidents reported by police decreased in 2020. Incidents between March, April, and May—when the strictest measures were in place — went down about 10% from 2019.

But experts, shelter operators, and women’s advocates say a different story was taking place behind closed doors. Calls to more discrete domestic abuse hotlines went up. The Observatory for Gender Equity, a coalition of academics and women’s rights groups considered a leading authority in tracking gender-based violence on the island, recorded a substantial uptick in femicides, or gender-related killings, during the first months of lockdown.

The Puerto Rico Police Department did not have comparable month-to-month statistics available. However, a Miami Herald analysis of data from the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics, a government agency, shows killings of women slightly increased between March and May of 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

In late January, Gov. Pedro Pierluisi declared a state of emergency over gender-based violence as one of his first acts in office. The goal: To dramatically reduce the number of women killed violently each year.

“The femicides we had last year, each and every one of them, is regrettable,” Pierluisi said in an interview with the Miami Herald. “We should put a stop to it. Gender violence in general... should be stuff of the past.”

As she searched through Puerto Rico’s humid forests, Santos remembered one of the last conversations she’d had with her daughter in a string of audio messages on WhatsApp. González had tried leaving the relationship before, but Roberto Rodríguez always beckoned her back. This time was different, she said. She’d get out once and for all— even if she had to call the police to kick him out.

“It is the only way to make him disappear from my life,” she said. “He won’t leave me alone.”

Early red flags after meeting at 13

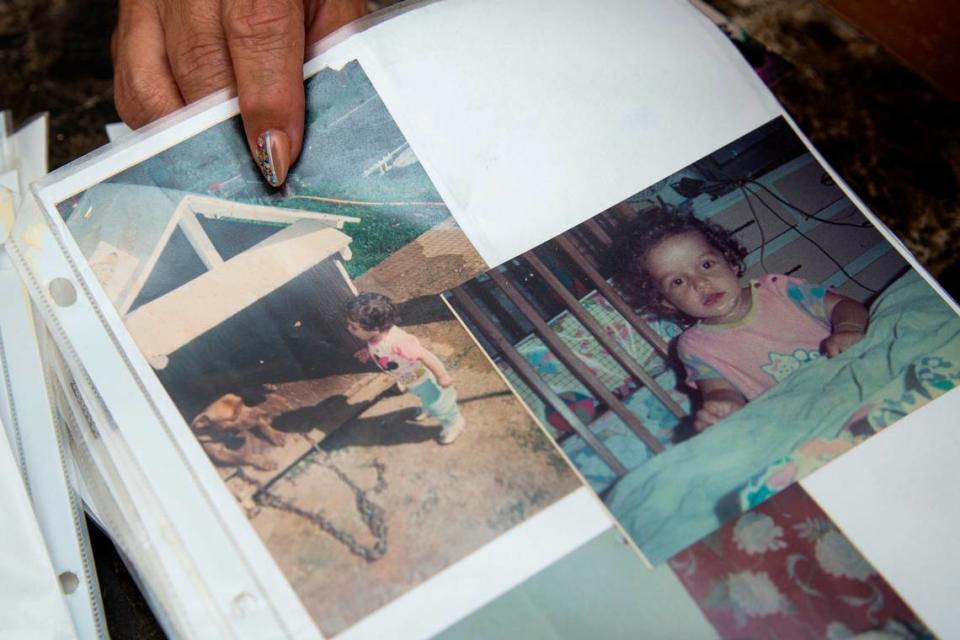

González came into the world fighting for her life. She was diagnosed with respiratory failure at birth and spent 13 days hospitalized. Her lungs eventually began to function properly, but doctors warned of possible brain damage.

Eight months later, she began to walk. Weeks later, she spoke. Within her first year, she was singing Puerto Rican classics like “En Mi Viejo San Juan.”

She grew up surrounded by a big family in Barranquitas, a small town nestled in the mountains. A hard-working student, she was elected class treasurer in the ninth grade. That’s when she met Rodríguez, who had a younger brother in her grade. She was 13. He was six years older.

“I didn’t like the relationship,” Santos said. “I didn’t like it at all.”

Her father forbade them from seeing each other but the two snuck around in secret. González’s grades took a nosedive. Thinking it was impossible to keep the two apart, her parents imposed new rules: He could only visit her at their home. But months after turning 15, González got pregnant.

Incensed, Santos went to the local police station to file a complaint against Rodríguez for having sex with a minor. Officers told her there was nothing they could do because Puerto Rico’s age of consent was 14, she said. In fact, it had increased to 16 three years before.

“They said, ‘If she had been fourteen, then yes, but she is already fifteen,” she recalled.

But when she brought up pursuing charges, relatives discouraged her, saying it wouldn’t change anything and would damage her relationship with her daughter. González’s parents turned their focus to keeping her in school, but Rodríguez insisted that she drop out. Santos managed to enroll her daughter in a vocational school. Rodríguez joined her, saying he wanted to become an electrician.

“That’s when I noticed that he did not want to leave her alone anywhere,” she said.

As the years went by, Santos’ fear grew. Her daughter became a nurse and found work at a hospital, but said Rodríguez forced her to quit. The young family, then with two daughters, got evicted from a rental home and ended up living in a car. González left him briefly, moving back in with her parents, but eventually took him back.

In private, she confided to her mother that Rodríguez had threatened to kill her, himself, and the girls. It was a stark contrast to the family man he painted himself to be in public, the one who showered his mother-in-law with love and praise.

The children also slipped details of their daily life.

“Abuela, daddy arrived yesterday and broke everything,” she recalled her eldest grandchild once telling her. “He broke my chair. He broke the DVD. He broke a bunch of things. Mami grabbed us and we hid in the bathroom.”

On another occasion, the girl said her dad yelled to their mother, “What if I slap you again like I did that one time?”

González’s uncle approached her about filing for a restraining order.

“It’s a piece of paper that won’t protect me at all,” she told him. “And I know that when I denounce him he is going to do the impossible to kill me and can kill the girls.”

Then came Hurricane María. Dirty stormwater flooded the young family’s home. In December 2019, daily earthquakes began rattling southwest Puerto Rico. The couple, now with three daughters, was living in her parents’ home. Though it wasn’t damaged from the quakes, it constantly shook.

Despite her troubles, González was “ecstatic for life” and in her few moments of respite, took her daughters out on outings around the island, her mother said.

“A girl who gave everything for everyone,” Santos said.

Lockdown hides trail of violence

In mid-March 2020, the island went into one of the strictest lockdowns in the United States. People were only allowed to leave home for essential tasks. Most businesses were shuttered and a curfew put in place. Women’s groups worried the measures would put those in situations of domestic abuse at even greater risk.

“Aggressors can use the lockdown situation like a tool of power and to exert control,” anti-violence coalition Coordinadora Paz Para La Mujer and over 30 organizations wrote then-Gov. Wanda Vázquez.

They asked for domestic violence shelters to be classified as essential services. Other local groups also raised the alarm. Kilómetro Cero, a human rights organization, along with 26 other groups, sent two letters to the Department of Public Safety asking police for a new way for women living in quarantine with abusive partners to file complaints. The Red de Albergues de Puerto Rico, a network of domestic violence shelters, asked officials to create a space for those who are COVID-19 positive.

All their letters went unanswered, said the heads of the organizations.

The governor did enact some policies to address gender violence. She had declared shelters an essential service by April and signed an executive order ordering all government agencies to prioritize services that offered women “prevention, protection, and safety” later in October.

But women’s advocates called the response slow and haphazard, not unlike what they’d seen after recent natural disasters. Following Hurricane Maria, hotlines used to report domestic violence and sexual assault were unreliable for weeks. Refugees International found that domestic violence police officers were deployed at blacked out roads to control traffic.

Femicides committed by intimate partners rose after the catastrophic storm, according to a 2019 study from Kilómetro Cero and Proyecto Matria, another rights group. The study—the most comprehensive on women’s killings in Puerto Rico to date—found that one woman is killed on the island every seven days.

The daily earthquakes that began rattling southwest Puerto Rico in 2019 further compounded the stress and devastation many families were experiencing.

The coronavirus and restrictions to curb its spread have created “a double pandemic,” said Vilmarie Rivera, director of the Hogar Nueva Mujer, a domestic violence shelter.

With the pandemic, calls for help rose from about eight to as many as 40 a day, she said. Women asked for childcare, emotional support and food. One year later, the group still receives around 30 inquiries a day from women looking for assistance.

The number of women identified as victims of domestic violence and assisted by the Women’s Advocate Office, an independent public agency that advances women’s rights on the island, rose considerably, from 64 in January to 127 by March.

The Observatory for Gender Equity has recorded 76 femicides in Puerto Rico from January 2020 to April 2021. They also registered an 83% increase in femicides in the first three months of the pandemic. The organization uses United Nations protocols to track femicides, incorporating figures from a broader range of crimes than those used by police; for example, the deaths of trans women, said analyst Débora Upegui-Hernández.

During the summer, the island ended the lockdown and made curfew later as it began to reopen the economy—a period during which overall femicides decreased. But as the economy opened, the number of femicides that were not tied to relationships increased, the analyst said.

Official police figures report 46 deaths of women and girls classified as homicides in 2020, up slightly from 42 the previous year. Those deaths include a range of causes in which few details are provided. One category, domestic violence, showed a decrease from 2019 to 2020. A 2019 Proyecto Matria and Kilómetro Cero study found that Puerto Rican police annually underreported femicides by as much as 27% compared to their findings.

Sgt. Axel Valencia, the police department’s press director, declined to address the discrepancy in detail, stating that, “The only statistics based on official data are those of the Puerto Rico Police.”

‘She was very afraid to leave’

González never stopped working at the nursing home during the pandemic, despite her own medical issues. She had been diagnosed with skin and breast cancer at 25 and also suffered from fibromyalgia.

“She could be very ill, but she worked,” said Karla Rodríguez, 31, González’s close friend. “She truly loved her patients.”

Roberto Rodríguez had already been in charge of watching the kids while she was at work before the pandemic. Now, the girls were at home around the clock trying to keep up with their learning without an internet connection. After shifts, González would collect class assignments at school and return them to teachers after her daughters completed them.

“She had no one who could help her at the time,” Karla Rodríguez said. “The pandemic, in that sense, made it harder.”

The two met a decade earlier. González never admitted that she was experiencing abuse. But Karla Rodríguez, who said she herself had been in an abusive relationship, picked up on signs. Her spouse called her constantly. And he didn’t like that she’d lost weight.

“That made him more controlling,” she said, recalling how he criticized her running clothes. “She looked very pretty and everyone was telling her so.”

Karla Rodríguez encouraged her to leave the relationship, but she was resistant: “She was very afraid to leave. But Angie didn’t show it often. No matter how bad things were.”

Earlier this year, though, González decided she’d had enough.

‘With a smile I say goodbye to the past,” she wrote in a Facebook post, hinting at major changes in her life. “I open the door to embark on a new path, always holding hands with God.”

Santos, recalling one of their last conversations, said her daughter was relieved.

“When she left him, she told me, ‘I feel so light. Like I took off 200 pounds off my shoulders,’” she said. “And I told her, ‘Angie, be careful, please be careful.’”

‘Maybe she wanted a breather’

Despite the efforts of advocates, women in abusive relationships found their options steadily narrowing as the pandemic paralyzed life in Puerto Rico.

Angela Jiménez, a legal advocate for domestic and sexual violence survivors who runs a virtual women’s empowerment group, said COVID-19 restrictions allowed abusers to isolate women.

“He cannot allow other human beings, family, friends, to reach the victim, because they will notice physical blows, emotional injuries, behavioral changes,” she said. “And then imagine, if we add to that the state telling you, ‘Look, victim, you now have to follow my instructions.’”

The Herald interviewed 13 of Jiménez’s clients, all domestic violence victims and survivors, and most said the pandemic had complicated their experience in some way. Over half said abusive partners had used the pandemic to exert control or threaten them.

Mental health providers limited in-person appointments or offered virtual appointments only, which for women living in close quarters with a violent partner, was not an option. Leaving home temporarily or escaping altogether required complicated planning. Court hearings went virtual and restraining orders can be requested online. But notifying aggressors of a protection order can take weeks longer, Jiménez said.

The virus has also complicated Puerto Rican Police Department’s operations— a force of about 12,000 agents accused in 2012 by the ACLU of “systematically” failing to police and investigate violence against women.

During the pandemic, police have been in charge of enforcing COVID-19 regulations. At least seven officers have died after falling ill with the virus, which has sickened hundreds of agents. At one point last year, there were over 1,000 members of the force in quarantine, said Valencia, the police’s press director.

Several police stations and divisions have also been temporarily shuttered as COVID-19 cases crop up in the force. In October, Puerto Rico’s 911 hotline was suspended for nearly 10 hours after call center employees tested positive for the coronavirus.

“Because someone got COVID, they have to close down the entire station,” Jiménez said. “When you call, they arrive two hours later. It affects when the victim goes to the police, and the police doesn’t want to transport anyone because of COVID, so they send the victim alone to court.”

Valencia said that “at no moment had service been interrupted” in any location temporarily shuttered because of COVID-19 infections.

As of April 5, there had been 16 femicides on the island in 2021, according to the Observatory for Gender Equity — on track to keep pace with last year’s figures.

Pierluisi’s emergency declaration includes measures like adding teeth to restraining orders by instructing officers to follow up with those who file for them. The governor is proposing about $6 million from local coffers and allocated an additional $2 million in federal money to finance public efforts against gender violence.

Activist groups in Puerto Rico are celebrating the governor’s decision, while also vowing to keep close tabs on how it is implemented.

“It seems that we are finally going to be able to address the issue of violence against women with the three parties that should always have been actively involved—government, organizations, and society,” said Amarilis Pagán, executive director of Proyecto Matria.

In January, when her daughter went missing, Santos went to the police to say that she thought Rodríguez knew what happened. In audio messages she shared with police, she said, he spoke about González in the past tense after she went missing and accused her of being a liar.

“My daughter would have never in her life left her three daughters,” Santos told an officer.

“No, but your daughter is young,’” she said he replied. “Maybe she wanted a breather.”

Cross along a mountain road

As Santos finished a long day of scouring the overgrown, humid forests, her cell phone lit up with a text message from her daughter’s 10-year-old child.

“Abuela, they took daddy prisoner,” she wrote.

Family members congregated outside of the police station in Barranquitas. An hour later, the police officer called from the neighboring town of Coamo.

“He said, ‘I need you to come here right now and at once to start preparing the funeral arrangements,’” recounted Santos, who had put the call on speaker so all the relatives present could hear. “My phone flew eight feet up. I started screaming, screaming, screaming. I couldn’t breathe.”

Roberto Rodríguez had confessed to officers that he had killed the mother of his children, officers later said. González was found dead at the base of a 30-foot precipice, alongside a desolate rural highway, not far from where her mother had searched.

“I would have found her,” she said, pinching her fingers. “I was this close to finding her.”

By the time Santos had arrived, an hour later, she said the officer, the same one who said her daughter had probably run away, had left the scene. She was not allowed to see her daughter, who had already been identified by a cousin.

“I got so angry,” Santos said. “I said, ‘You know why the police officer left? Because he’s ashamed. He said my daughter needed a breather.’”

In response to questions from the Herald about the handling of González’s case, Valencia said the current police commissioner, Antonio López, is working to expedite investigations, protect victims and hold officers accountable, creating a crimes against women unit within the force.

“The Puerto Rican police has dedicated its resources to support this fight,” he said.

Roberto Rodriguez’s family did not respond to a request for comment. He remains behind bars and is being represented by a lawyer from a free legal clinic, Julio Torres, who said he was waiting for more information through the discovery process to “have a clearer vision of what happened” before commenting.

It has now been almost three months since González was killed. Santos is still Barranquitas, taking care of her grandchildren. The three girls still live in the blue house at the bottom of a hill that they shared with their mother, father, and grandfather. The family’s cats and chickens roam the road framed by feathery eucalyptus trees. A 10-month-old, black Great Dane puppy that González named Grandote and gifted her daughters spends his days watching the sheep and other animals.

At the spot where González was found, her family erected a pink cross. At the center is an illustration of her, smiling in blue scrubs, white wings sprouting from her back. The colorful memorial is covered in plastic purple orchids, pale daisies, lilac roses, and golden sunflowers, her favorite.

Santos hopes the emergency declaration will empower women to seek help and laments that her own daughter suffered in silence. After her death, Santos learned of an organization offering help for domestic violence victims less than 15 miles from where González was living.

“Many times we told her, ‘We can help you. You have to get out of this,’” she said. “But she said she couldn’t because he was going to kill her. He was going to kill her.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies