Here’s why trial of officer who shot Atatiana Jefferson should stay in Tarrant County

Aaron Dean and his lawyers have every right to be concerned about the venue for his upcoming murder trial in the shooting of Atatiana Jefferson.

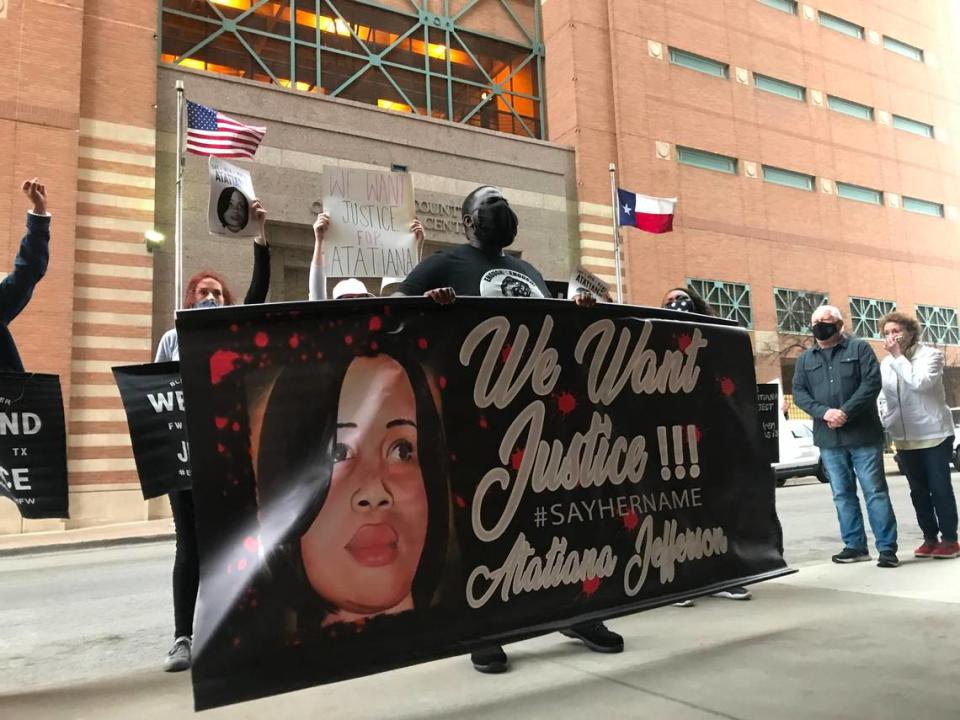

The case drew international attention from the moment Dean, now a former Fort Worth police officer, shot Jefferson in October 2019. The facts of the case have been repeated again and again since, over the long delays caused by the pandemic and the ongoing debate about police use of force against Black people.

But Tarrant County is a big, diverse place, full of plenty of fair-minded potential jurors. Dean’s request for a change of venue for his trial, set to begin Jan. 10, is understandable but unnecessary. It’s important that the trial be here, that Tarrant County residents deliver justice in the case.

Heavy news coverage does not necessarily mean a biased jury pool. Even those already exposed to some of the facts of the case may not have formed opinions. And while this may come as a surprise to those diving deep enough into the news to read this editorial, many people are oblivious to the back and forth of the daily news.

Most are no doubt aware of the shooting. The circumstances were shocking, with Jefferson, 28, shot in her own home by an officer dispatched because of a neighbor’s concern that her door was open late at night. But those following the case closely are a tiny portion of Tarrant County’s 2.1 million residents.

For recent precedent, look no further than Dallas County, where a judge denied a similar request from former Dallas officer Amber Guyger. Her legal team argued that pervasive news coverage made a fair hearing impossible.

The jury convicted Guyger, who shot Botham Jean in his apartment in 2018 after mistakenly thinking she was in her own home. But there have been no indications of tainted deliberations or bias. An appeals court has already upheld the murder conviction.

The same jury sentenced Guyger to 10 years in prison, much less than prosecutors sought. Clearly, the jurors were capable of some leniency.

In Dean’s case, it’s important that the jury reflect the community, and that’s sometimes a problem when high-profile trials are moved from large cities and counties to smaller ones. Tarrant County has an ample pool to produce a fair, diverse jury.

It will be the job of the court and lawyers on each side to weed out bias. After all, it’s not just media coverage that’s at issue. Plenty of potential jurors will have strong opinions about police, for and against, and the verdict in Dean’s case shouldn’t be determined by such predetermined feelings.

Of course, it’s paramount that Dean, who could face life in prison, get a fair trial with an impartial jury. In recent months, emotional reactions to high-profile cases, especially those around the explosive issues of race, have reminded us of the importance of upholding the principles of our legal system. Defendants who aren’t favored by public opinion deserve legal protections, too, and may need them most of all.

Citizens also deserve to know that the system worked even if the outcome wasn’t necessarily what they wanted.

So, Judge David Hagerman should give full consideration to Dean’s motion and the arguments set forth by his attorneys in a hearing scheduled for Dec. 13. (Among the evidence cited by the Dean team, we should note, are numerous Star-Telegram stories.)

But Hagerman should move expeditiously, too. This trial has waited long enough. Jefferson’s family and the entire city need resolution to this tragedy.

And it should be the product of a jury of Dean’s peers in Tarrant County.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies