Why You Shouldn’t Be So Quick to Judge Rappers for Their Bling

It’s no secret that rappers have a long-running love affair with jewelry. More than a fashion statement, artists’ bling is a flex, a status symbol, a token of brotherhood, and most importantly, a screaming message of success.

While gold chains and expensive watches have been common accessories for hip-hop artists ever since they burst onto the scene in the late 1970s, rappers’ jewelry game has risen to new heights with diamond-encrusted grills, iced-out Rolexes and Pateks, blinding rings, and of course, the all-important chain.

But beyond the frenzy around the eye-watering price tags, or the dog-whistle criticism over rappers blowing wads of cash on diamond-encrusted jewelry, the conversation ends there. (Save Lil Uzi Vert’s decision to have a $24 million pink diamond embedded into his forehead, of course.)

For director Karam Gill, there was much more to be said about the relationship between rappers and jewelry. “No one has ever taken time to think about anything deeper beyond the fact that people are wearing million-dollar chains showing up to the grocery store,” Gill told The Daily Beast ahead of the premiere of his new YouTube Originals docuseries Ice Cold at the Tribeca Film Festival on Sunday.

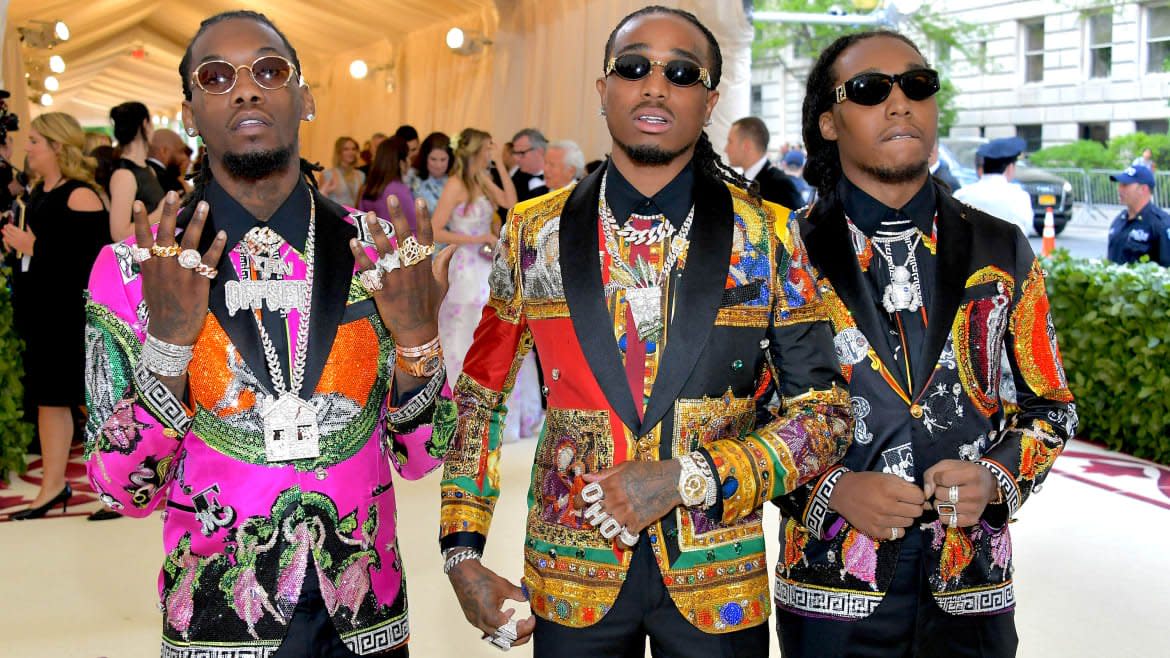

The four-part film was executive produced by Atlanta rap trio Migos and will premiere on YouTube July 8. It boasts interviews with some of the rap industry’s biggest names, including Migos, A$AP Ferg, JT and Yung Miami from City Girls, Lil Yachty, French Montana, J Balvin, Lil Baby, and Quality Control record label founders Kevin “Coach K” Lee and Pierre “Pee” Thomas.

Rick James’ Intense Rivalry With Prince Nearly Came to Blows

“I was really interested in this particular entry point to hip-hop and jewelry, because it’s been around so much and everyone sees it,” Gill explained. “I wanted to explore beyond the prices, beyond the style, and what does it mean beyond just jewelry.”

Gill is making a name for himself by diving into the world of hip-hop and exploring how these stories and themes play out in a cultural context. Earlier this year, Gill’s Showtime docuseries on the rainbow-haired rapper 6ix9ine, Supervillain: The Making of Tekashi 6ix9ine, made news when he flat-out said he thought the 25-year-old rapper was “truly a horrible human being.”

Gill said he had no interest in making a film solely about 6ix9ine but wanted to expose the rapper for who he is and, at the same time, analyze the public’s fascination with a Joker-esque character and what that says about society.

He takes the same approach with Ice Cold. Instead of drooling over the artists’ flashy drip Gill pulls back the curtain to reveal what lies at the heart of the relationship.

It all stems from the concept of the American Dream—the idea that through hard work and determination, anything is achievable in the United States. However, the American Dream is hard to attain for those who have an entire system stacked against them.

For Black communities who’ve suffered through centuries of oppression, unfair housing, and banking and hiring practices, it was a laughable notion that by working just a little bit harder, Black people could achieve the same success as their white peers.

The birth of rap coincided with a Wall Street boom that emphasized wealth and luxury—juxtaposed with the crack epidemic of the early 1980s that was crippling Black communities.

At the time, there were few examples of successful Black businessmen; rather, the men who were feared and respected in Black communities were the drug dealers and the pimps, who donned flashy gold chains, watches, and rings.

So, rappers began to emulate these signs of wealth and power that they’d seen from men who they perceived to be successes. “The rappers wanted to be drug dealers, the drug dealers wanted to be rappers,” Brooklyn-born rapper Talib Kweli recalled in the film.

Yet, while it’s perfectly fine for Elizabeth Taylor to amass a dazzling collection of gems, it’s somehow looked down upon when a Black person does the same.

“I’m fascinated by the concept of the American Dream,” Gill said. “You know, as a person of color, that concept to me is so fascinating. I think the American Dream is not a one-size-fits-all. I think that the same way people spend six figures on a country-club membership yearly, or might have a wine collection that’s in the millions, what is the difference between that and buying a chain? It’s just a different rendition of what your American Dream is.”

“In Indian cultures, people save their whole lives to blow a million dollars in one night for a wedding,” he explained. “If you look at country club culture in the South, people will spend millions over the course of a decade, blowing money. But when rappers buy jewelry, it’s frowned upon. I don’t understand why that is. I think it speaks to a lot of bias that we have as a society.”

Rappers fantasize about designing their next chain. In Ice Cold, J Balvin shared a story about how fascinating he found the process of picking out gemstones and working with a jeweler on the design of his piece. Throughout the docuseries, rappers show off their drip, rattling off the prices and recalling when they got each shimmering item.

Chains also represent a brotherhood of sorts, with record labels bestowing custom-made pendants to new artists—akin to a king knighting a loyal servant. They are sometimes gifted to outsiders, such as when Jay Z signed off giving Naomi Campbell, Robert De Niro, Victoria Beckham, and model Karolina Kurkova the coveted Roc-A-Fella chain.

There are, of course, obvious downsides to rappers’ obsession with having the swaggiest bling: it makes them prime targets for armed robbery.

It’s also become an expectation that artists fork over hundreds of thousands of dollars for appearance’s sake. City Girls duo Yung Miami and JT admitted they wouldn’t bother giving the time of day to any man who wasn’t wearing some serious hardware. “If you don’t got no jewelry on, you look broke,” they laughed in the film.

Gucci Mane performs onstage during the BET Hip Hop Awards 2018 at Fillmore Miami Beach on October 6, 2018, in Miami Beach, Florida.

Plus, spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on flashy, custom-made pieces isn’t exactly a smart investment. Celeb-favorite jeweler Johnny Dang explained how he can’t resell anything unless it’s melted down, the gold and diamonds repurposed into something new.

A year after Lil Yachty gleefully displayed his eye-opening collection, complete with an iced-out “Yachty Simpson” pendant, he barely wanted to touch his jewelry. “I don’t buy jewelry no more,” he said. “It’s shit that doesn’t matter in the real world.”

“It’s fucking rocks, technically. From the ground, rocks, a mineral. I don’t really care anymore,” he added, saying he was starting to drift away from the “materialistic stuff.”

Lil Yachty confessed that when he was wearing all his chains, it was beginning to feel like he was a caricature of himself. “I have two lives,” he said. “My personal life and rap life. I’m not a rapper right now, I’m Miles. So, I can’t fake and put this shit on because I really don’t want to. I only put it on when I’m in rapper mode, it’s like a costume. I don’t really give a fuck now. It’s cool to look at, I guess. I don’t like putting it on, it’s too much.”

But overall, Gill said he believes there’s nothing wrong with hip-hop’s jewelry fixation. “I think that it requires context to understand,” he concluded. “It should be treated, ultimately, like any extravagant material purchase that our society has accepted.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies