How tracking ethnicity and occupation data is helping fight COVID-19

The knock on Sanjay Chada's door was unexpected.

It was a woman from Indus Community Services, a non-profit that serves the large South Asian population of Peel Region, located just west of Toronto. She wanted to know if anyone over 18 had not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine.

Chada said his 29-year-old son, Akash, was the only one.

"She took my phone number and left," said Chada. "After an hour, we got a call with a vaccine appointment for him.

"It took me three weeks to get my shot after I made an appointment. He got his in three days."

Brampton, Ont., where Chada's family lives, was one of the hardest hit by COVID-19 in Canada. But it's also been ground zero for massive campaigns to get people vaccinated against and educated about the disease.

Indus, along with other community groups, has been able to play a crucial role because Peel's regional government has been radically transparent with its COVID-19 data, disclosing details about outbreak locations, making public the race of people who test positive and providing caseload maps broken down to sub-neighbourhood levels.

"It showed us early on that the South Asian community in Peel was being disproportionately impacted by the disease," said Indus CEO Gurpreet Malhotra.

In most of the country, this would be impossible because such detailed information is either not collected or not made public.

Flying blind

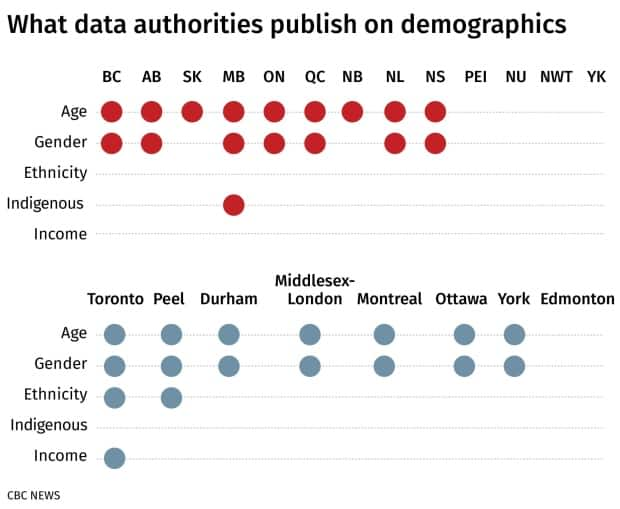

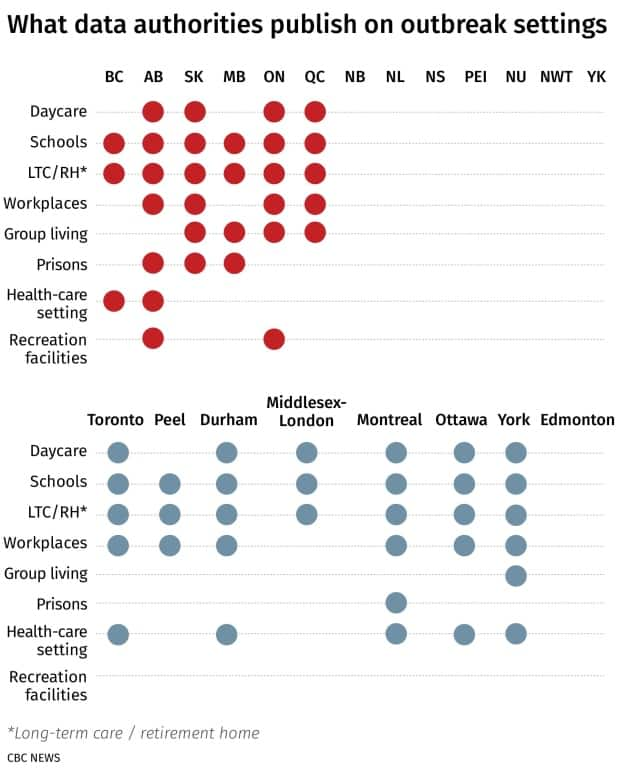

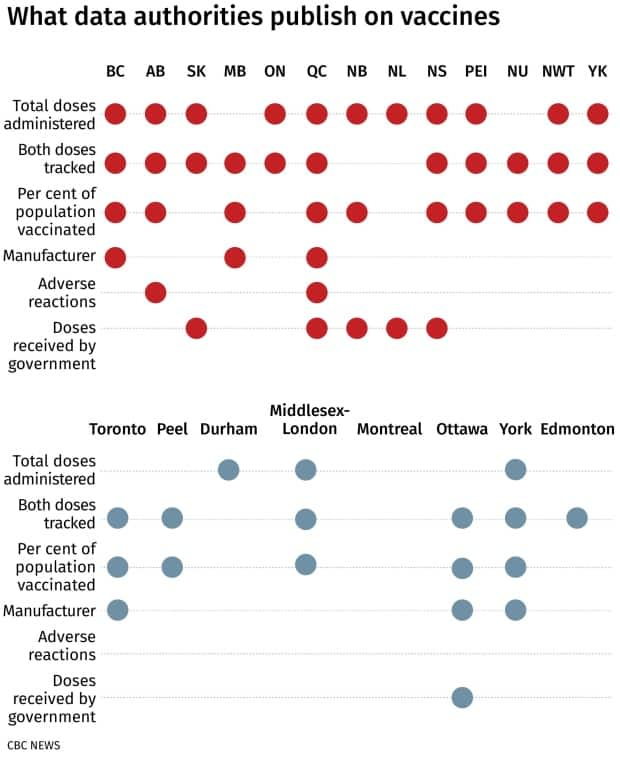

CBC News compared COVID-19 data published by every province and region. Only a handful publish data on race, income, occupation and neighbourhood-specific breakdowns of infections and vaccinations — information that health officials and community leaders say helps them intervene quickly in hotspots.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) requests this data from the provinces, but spokesperson Anna Madison said it is selectively and inconsistently reported, with only half of provinces sending data on race and occupation.

She declined to say which provinces do not report this information.

If there are future waves of COVID-19, or other new health crises, most parts of the country will be flying blind, putting racialized Canadians and those in frontline occupations at risk, say researchers and community leaders interviewed by CBC News.

"South of the border, they've got data on income, race, occupation, which shows disparities. In the U.K., they've got data on race, income and occupation, which shows disparities," said Dr. Kwame McKenzie, CEO of the Wellesley Institute, an urban health think-tank in Toronto.

"In Canada, we're not collecting. So something's going wrong."

How data helped avert a crisis

In many ways, Peel Region was set up for a crisis — but also for a solution.

One-third of its 1.5 million residents are of South Asian descent, and many households are either multi-family or multi-generational. Two nearby colleges, Sheridan and Humber, host a large number of international students, many of whom rent spare rooms in local homes, sometimes several to a space.

A disproportionate burden

Peel is also home to huge Amazon fulfilment centres, a Canada Post sorting facility, Toronto Pearson International Airport and essential industrial facilities that have set up next to the airport — all places where many of these students work part time.

"A lot of these students … can't sit at home. They're not getting money from back home. They don't have the benefit of taking two weeks off work if they get sick," Chada said.

All ideal conditions for a virus that spreads through prolonged close contact.

But being large and densely populated also gives Peel resources.

Its health unit is led by Dr. Lawrence Loh, who has been praised for taking on Amazon and ordering the shutdown of workplaces despite furious resistance. He also has a large team of epidemiologists well versed in data analytics.

"We recognized very early on that sharing data, particularly around things like occupation, could actually help develop a clear picture of how the pandemic is unfolding in our community and also allow us to identify areas that may require attention," said Loh.

A recently published map showing vaccination rates by postal code is helping the region be more strategic in its vaccine rollout, he added.

"So that's why we have pop-up clinics in these locations," he said. "That's why we have community agencies and partnerships. To actually get in there."

It was this data that allowed Indus to lobby the Ontario government, receiving $750,000 as part of the province's High Priority Communities Strategy. The group mounted a media campaign in several Indian languages, including Hindi and Punjabi. They hired people to knock on doors, help with vaccine appointments and dispel myths about vaccines among those hesitant. They rallied community leaders to talk to people at community halls and houses of worship.

They also provided transportation and hotel rooms for infected people who needed to isolate. They provided Indian-style meals for seniors, not offered by the local Meals on Wheels. They bought personal protective equipment (PPE) that could be worn with a turban and beard by Sikh men.

And they were able to give some relief money to people who had to stop working and fell behind on rent.

Publishing detailed COVID-19 data doesn't guarantee public health interventions will be effective, or that outbreaks will be controlled quickly.

But in Peel's case, it may have prevented a precarious situation from becoming far worse.

"Imagine if we hadn't named Amazon as a problem, if we didn't have pop-up clinics in hesitant communities," said Malhotra. "This got more people vaccinated, [provided] more information so they could make informed choices."

Less data in B.C.

Several provinces over, in Metro Vancouver, the picture looks very different.

Dr. Birinder Narang is part of a group of South Asian doctors that spent months asking the B.C. government to release neighbourhood-level infection rates.

"We had been seeing for a while this disproportionate rise in cases in areas that are predominantly South Asian," he said. But because the province didn't release data beyond the municipality level, it was impossible to know for sure.

Like other provinces, British Columbia does not collect ethnicity data on COVID-19 infections or immunizations. The best Narang could hope for was community-level data that could be cross-referenced with five-year-old census data on ethnicity.

It took B.C. more than a year to release even localized information — and it only did so after a data leak proved the provincial government was collecting it. It showed significantly higher rates of COVID-19 in the Metro Vancouver neighbourhoods home to the highest proportions of South Asians and recent immigrants.

Had the province released this data sooner, Narang said the response from public health and local community groups would likely have looked a lot more like Peel's.

"Outreach and targeted messaging within the media — culturally specific, culturally relevant messaging — and much more targeted vaccination in hotspot communities much earlier in the campaign."

Privacy, stigmatization concerns

The most common reasons health officials gave for not releasing such information were privacy concerns and the potential of stigmatization for affected communities.

The Manitoba government released a report on the ethnic breakdown of COVID-19 cases in its province, but does not provide that data by geographical area or as part of daily releases.

"Manitoba's population is much smaller than that of larger jurisdictions, and some of the Prairie clichés of everyone knowing each other have some truth to it," the press secretary to the province's health ministry said in an email.

"Throughout the pandemic, we have preached the need to avoid stigmatization, as it is an ally of the virus."

In Manitoba, this is particularly true with respect to Indigenous communities. Both the federal and Manitoba governments provide data on infection and immunization rates among Indigenous people, but it isn't community specific.

In some parts of the country, notably B.C., Indigenous leaders have had to fight to get timely information about infections in nearby areas, again due to concerns around privacy and stigma.

Peel's top doctor argues that data can, in fact, counter stigma. Early in the pandemic, when Peel had high case rates, there was widespread assumption that the region's population wasn't following public health directives.

"We were able to come out and say, it's not that people aren't following the regulations, it's in fact the fact that these people are working in jobs that cannot be done from home," Loh said.

"It's not the data itself that leads to the stigma and discrimination, but it is the inability to understand the full story behind the numbers."

McKenzie noted that when data was publicly released in Toronto last year showing COVID-19 rates were nine times higher in the Black population versus the white population, a focused public health response dropped that figure to just under double within a few months.

But elsewhere in the country, he said, the lack of data is putting vulnerable populations further at risk, which has implications for future disease outbreaks.

"Personally, I believe it should be illegal to not collect data. You should have to prove that in Canada, when you're setting up public services — especially vital public services in a pandemic — that you are setting them up in an equitable way."

About this story

CBC News looked at every COVID-19 data website published by provincial and regional health authorities, and made an inventory of the types of information that were disclosed. For each category of COVID-19 data (for example, cases, deaths, hospitalizations, vaccines), we noted the specific variables available (for example, cumulative numbers, new daily numbers, rates, whether cases are lab-confirmed or epidemiologically linked).

The full inventory is available here, updated as of June 10. Authorities may have since changed their websites.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies