‘Why was there no safety?’ Couple seeks change after son died in scaffolding collapse

On the morning after New Year’s Day, Charlotte bricklayer Osman Reyes was on the seventh floor of an apartment building under construction when he heard the sound of crashing metal.

He raced down the stairs and outside, where he saw what he prefers not to describe. His stepson and two other construction workers were lying on the ground amidst boards and rubble.

Jose Bonilla Canaca, just 26 years old, had been helping lay brick on the building’s exterior alongside Gilberto Monico Fernández and Jesus “Chuy” Olivares. When scaffolding they stood on collapsed, they plummeted 70 feet to their deaths.

“It’s an empty space,” Osman said of the loss nine weeks after Jose’s death. “We try to overcome it. But we can’t.”

Why the scaffolding on the uptown Charlotte apartment building gave way remains unclear. The state Division of Occupational Safety and Health is still investigating.

While they wait for an explanation, Jose’s family is calling for stronger efforts to keep construction workers safe. Regulators and company managers failed to take steps that might have protected the workers, they say.

“I want there to be more safety so this will never happen again to Latino families,” Jose’s mother, Iris Bonilla, said through an interpreter at her east Charlotte home. “Because their parents, mothers, sons – they’re waiting for them to come back home.”

None of the three victims were wearing safety harnesses when they died, family members said. When working at heights, construction workers sometimes wear harnesses that are tied to the building — a precaution that prevents them from falling long distances.

But federal rules generally don’t require such safety harnesses when workers are standing on scaffolds that are surrounded by guardrails — the type that collapsed on Jan. 2.

They should be required, Osman said. “They need to implement a law for people to use these kinds of harnesses in those places,” he told The Charlotte Observer.

What went wrong?

The site of the tragedy — a rising 16-story apartment complex on East Morehead Street — is one of more than 200 commercial and multifamily construction projects underway in Mecklenburg County. The builder is Hanover Company, a Houston-based general contractor. Jose worked for Friends Masonry Construction, a Charlotte-based subcontractor.

Osman said he was concerned about the safety of scaffolding on the East Morehead Street construction site before the three men died because it appeared to be unstable. He approached an employee with Old North State Masonry, the company that erected the scaffolding, to ask about that, he said. He was told it had been put up properly.

Based on investigations into previous scaffolding collapses, workplace safety inspectors may be examining whether scaffolding at the Charlotte site was erected properly and whether it was overloaded. Following a 2015 scaffolding collapse in downtown Raleigh that killed three men, investigators found that a Durham-based company had not properly tied the scaffolding to the building and had loaded it with too much weight.

Getting to the bottom of what went wrong in Charlotte will require investigators to win the cooperation of workers who were at the job site. Officials with the Charlotte-Metrolina Labor Council earlier this month asked the state to apply a federal policy that temporarily protects undocumented workers so all who witnessed the collapse can safely talk to inspectors.

Many workers at the East Morehead Street construction site were undocumented immigrants who have not returned to work since the tragedy, the labor council said in a letter to state labor officials. Ashley Hawkins, the labor council’s president, said she and her colleagues have talked to several workers who said they witnessed the scaffolding collapse but were instructed not to share what they saw.

Reached by phone earlier this month, one Friends Masonry Construction owner, Alejandro Sanchez, said none of his workers were instructed to remain silent about the accident. “They can talk to whoever they want to,” he said through an interpreter.

Deaths rise, inspections fall

In North Carolina, at least 16 people have died in scaffolding-related incidents over the past decade, OSHA records show.

“I’d like to never see an accident like that happen again,” said Osman, who noted that no one involved with the state investigation has talked to him about the collapse. “I’d like to see the authorities responsible for construction sites implement more security measures for the workers.”

Osman’s concerns come at a time when the number of workplace safety and health inspections in fast-growing North Carolina have dropped by more than half over the past decade. Deaths on job sites rose sharply during that period, the Observer found. OSHA officials conducted fewer than 2,000 inspections last fiscal year — just one inspection for every 172 employers.

“OSHA has failed in this area,” Osman said.

Osman has worked in construction in Charlotte for 16 years. On the rare instances when he has seen OSHA officials show up at work sites, he said, they have checked whether workers were wearing protective gear such as hard hats, safety glasses and steel-toed boots.

“But they don’t check the scaffolds,” he said. “We’d love to see an improvement in that.”

State labor department spokeswoman Erin Wilson says workplace safety inspectors do inspect scaffolding on the job sites they visit. In fiscal years 2021 and 2022, they issued 500 citations for scaffolding violations, she said.

When she awakes each morning, Jose’s mother said the first thing she thinks about is her son.

If there had been more inspections and safety precautions on her son’s work site, she asks, would he still be alive today?

“All these big companies need to focus on the safety of their employees,” she said.

Are lawsuits ahead?

Questions about who’s responsible for the tragedy will likely play out in the court system before long.

The families of both Jose and Jesus Olivares have hired lawyers. Vernon Sumwalt, a Charlotte lawyer representing Olivares’ family, said he expects to file a wrongful death lawsuit. While it’s too soon to say exactly what happened on Jan 2, Sumwalt said this much is clear:

“These things don’t happen by accident,” he said. “These things could have been prevented.”

Camille Payton, a Charlotte lawyer representing Jose’s family, said she’s not yet sure whether the family will sue. But she said she’s concerned that Hispanic workers are dying on job sites at higher rates than others. Hispanic people make up about 27% of workers on North Carolina construction sites, but more than 40% of those dying on the job, federal data show.

“We want them to have access to the same protections our laws provide to everyone else,” she said.

Payton’s law firm has notified Old North State Masonry and Hydro-Mobile, the company that designed and manufactured the scaffolding, that it is representing the family.

No one from those companies responded to requests for interviews. Sanchez, one of the Friends Masonry Construction owners, said he didn’t want to discuss the accident because it is still under investigation.

Raleigh attorney David Fothergill represents Hanover Company, the general contractor for the apartment building project. The company “shares its compassion and sympathy with those involved in this unfortunate incident,” he wrote in an email. But he declined to comment further.

From youth to death

In 1999, when Jose was 2, he and his family came to Charlotte from Honduras. Much of their home country had been devastated by Hurricane Mitch, and Iris and her late husband were hoping for a more stable place to raise their son.

As Jose got older, he made a happy life for himself in Charlotte and began working in construction about three and a half years ago, family members say.

Jose had been working at a different Friends Masonry job site. But on Jan. 2, he wasn’t needed there. Not wanting to lose a day’s pay, he asked a supervisor if he could move to one of the company’s other construction sites, family members said.

Early that morning, he was sent to the site where his stepfather was working, the apartment building under construction on East Morehead Street. He and his stepdad had never before worked on such a tall building, his parents said.

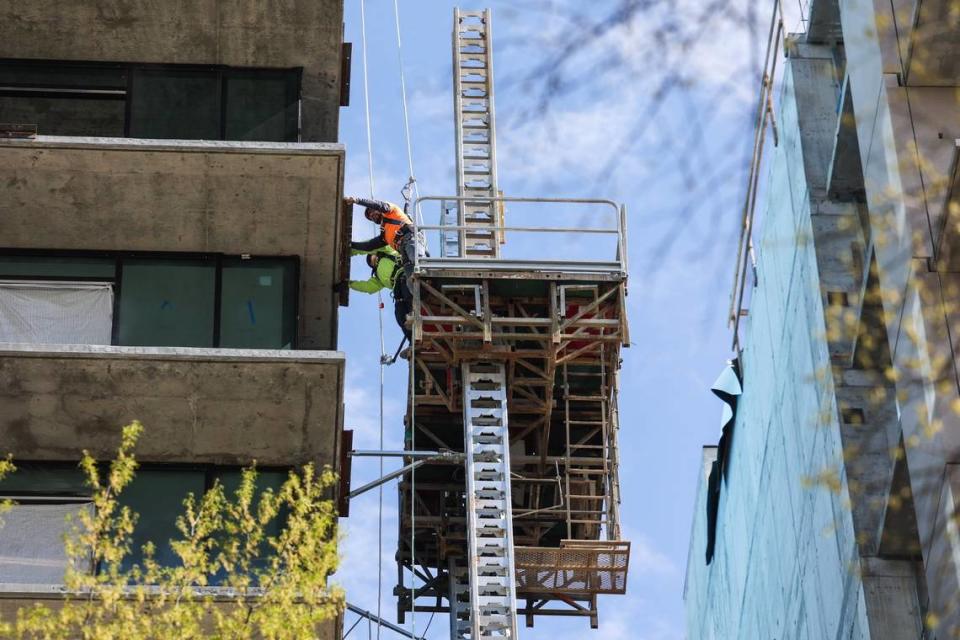

With five other men, Jose climbed onto the platform of a “mast climber scaffold,” a motorized device used to move people and supplies up and down the facades of tall buildings. Jose’s job was to pass bricks and other material to bricklayers.

Around 9 a.m, the scaffolding gave way, according to the police report. Three workers on the platform were able to jump onto balconies, Jose’s family members said. But Jose and the other two workers weren’t so fortunate.

A nearby crane operator called 911 to report what he saw: After the scaffolding fell, people were lying motionless on the ground.

“I see three bodies laying down there,” he said. “I hope they’re not dead.”

Asked about what happened that morning, Osman looked toward the floor, his facial expression somber. “I don’t like to touch that,” he said.

Jose’s mother described what her husband told her. After racing down the seven flights of stairs and seeing his stepson’s body, Osman wanted to go to his side, his wife said. But a police officer told him he couldn’t.

Soon afterward, Iris said, an officer took him aside to break the news. “I’m sorry, Osman, your son has passed away.”

Clinging to memories

At the one-story ranch home that Iris shares with Osman, little hangs on the avocado-green walls of the living room. But two large photographs command attention. One shows Jose with his arm draped around his sister, Amy, at her 17th birthday party last year. Another shows Jose bespectacled, head tilted and looking content as he sat in a boat and held the first fish he’d ever caught – a foot-long bass.

Sitting on a couch beneath the birthday photograph, Iris lifted her eyeglasses to brush away tears as she reminisced about her son.

Jose lost his father to a heart attack nine years after arriving in the U.S., she said. Until Iris married Osman in 2010, she was Jose’s sole parent. Despite his grief over losing this father, he grew into a loving, happy man, his family said.

At 6 p.m., almost every evening, he’d call his mom to ask how she was doing and to tell her he loved her, she said.

He loved playing soccer, skateboarding with friends, and fishing in Lake Norman and Lake Wylie. After taking selfies with the fish he caught, he would always throw them back in the water.

Jose’s uncle, Jorge Bonilla, said he was an easy-going guy who loved making people laugh with silly jokes.

“Always joking,” the uncle said. “I used to make fun of him: ‘Here comes the comedian!’ ”

Jose didn’t plan to work in construction forever. His dream was to become a chef.

At the home he shared with a friend in east Charlotte, he loved preparing Italian, Greek and Mexican food, his uncle said.

One of his signature dishes: stuffed chicken, a bird cooked with rice, potatoes and ground beef.

Two days before he died, Jose spoke with his mother on the phone for two hours, she said. He talked about his goals for the new year and his plan to study so that he could become a chef.

“I never thought it would be the last call,” she said.

‘A pain in my heart’

These days, Iris is so haunted by what happened that she often finds it hard to sleep.

“Every day, there is a pain in my heart,” she said. “ … Because I will never hear his voice again.”

Osman said he was so traumatized that he did not return to work for two months after the tragedy. He has sought counseling.

“I’m not myself,” he said.

Jorge, Jose’s uncle, is also in construction. He owns a small maintenance company, which employs two workers to do repairs, renovations, painting, plumbing and electrical work on homes.

Today, he said, the tragedy still leaves him feeling “paranoid about things” on his job sites. He takes extra care to ensure his workers are safe, he said.

“If a small company like mine can do all these things, why can’t a big company do the same?” he asked.

La Noticia and Observer staff writers Gordon Rago and Gavin Off contributed to this story.

Esta historia se puede leer en español en La Noticia.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies