We independently evaluate the products we review. When you buy via links on our site, we may receive compensation. Read more about how we vet products and deals.

Why Hugh Grant Deserves All the Awards for 'Florence Foster Jenkins'

By Carrie Rickey

All the way back in 1994, Hugh Grant took home a Golden Globe for Best Actor — Musical or Comedy for his performance as the befuddled bachelor in Four Weddings and a Funeral. As it happens, that was the last major award Grant would win in his career so far. Because his filmography favors comedy, he isn’t the kind of actor ordinarily collecting trophies this time of year. That’s a shame, because some of Grant’s best work — including Weddings, 1996’s Sense and Sensibility, 2002’s About a Boy, and 2016’s Florence Foster Jenkins — is edged with a ruefulness and angst that only he can supply.

Happily, Grant is in contention again this year at the Globes: He’s nominated for Best Actor — Musical or Comedy for Jenkins. The Golden Globes (airing Sunday, Jan. 8, on NBC) recognize that the difference between a drama and a comedy performance is, in the words of director Nancy Meyers, the difference between hitting the bull and hitting the bull’s-eye. Other actors could have played fellow nominee Casey Affleck’s role in the acclaimed drama . But who else expresses self-love and self-loathing like Grant does as the kept husband of Meryl Streep’s terrible soprano? He deserves the Globe, an Oscar nomination, and the recognition — finally — that he is unique and irreplaceable among modern actors.

Related: Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant on How They Would Handle an Untalented Co-star

It took Grant a long time to distinguish himself from the other bright young Brits in the 1980s. His movie debut in Privileged (1982), as a high-born debauchee at Oxford, suggested that he was a nob. In subsequent roles — Maurice (1987), The Lair of the White Worm (1988) and Rowing with the Wind (1988) — he played so many young lords, I figured him for a born aristocrat. I was surprised to learn that he actually came from a middle-class background: his father was in the carpet business and his mother was a schoolteacher, and Grant went to Oxford on a scholarship.

Most movie fans agree that Hugh Grant became “Hugh Grant” in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994). Director Mike Newell’s ensemble film (written by Richard Curtis) prominently featured Grant as a walking contradiction: a reticent, stammering singleton who multiple women wanted to couple with. (Many Grant films have his female co-stars taking the initiative, saving his character rather than the other way around.)

For me though, “Hugh Grant” first revealed himself as early as 1991, in the costume drama Impromptu. Grant played the reticent and fragile Frédéric Chopin, who is stalked by Judy Davis’s aggressive and sturdy George Sand. She wears men’s trousers and waistcoats. He speaks with a Polish accent. When she reveals herself in his boudoir, his nostrils flare and sarcasm radiates from his every orifice. “Rumor has it that you are a woman, and so I must ask you to leave my private chambers,” he commands. Watch the scene below:

Until Impromptu, I regarded Grant more or less as a hair actor, a male Veronica Lake who tossed that forelocked “Eton flop” for effect. Yet for the first time in Impromptu, I heard his unusual phrasing, marveling how he treated words like elastic, stretching and snapping them for comic effect.

Grant’s body language, as exhibited in a string of Richard Curtis ensemble comedies — Four Weddings followed by Notting Hill (1999) and Love, Actually (2003) — is likewise eccentric. He is the opposite of hard-bodied hero, a slack-limbed gentleman with a hint of dowager’s hump and an absence of muscle tone. The body English says, “No heavy lifting.” The spoken English, however, lightens the spirits.

Related: Hugh Grant Was ‘a Little Bitter’ When He Didn’t Get Nomination for ‘About a Boy’

“They say acting is based upon retrieving past emotions,” Grant observed in a 2003 Premiere magazine interview, adding, “but I don’t have any emotions to speak of.” Rather than emoting, he prefers “behaving.” For him behaving “is how you think you should be, against what you’re really feeling.” Essentially, he rejects the method-y soul-plumbing of actors such as Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro, and Denzel Washington. Grant is less interested in revealing what lies beneath than he is in sweating behind the masks he wears to conceal what lies beneath.

Back then, Grant specialized in hugely engaging portraits of fellows trying, and failing, to hide who they really are: Charlie, his Four Weddings character, not daring to love for fear his feelings won’t be reciprocated; William Thacker in Notting Hill, besotted with an American actress and afraid she’s out of his league; his prime minister in Love, Actually, unable to hide his lust for the tea girl.

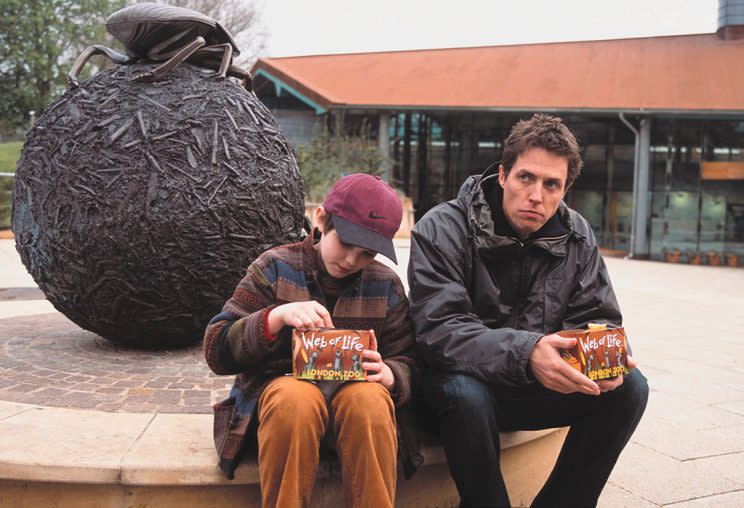

Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) is an important transitional role in the Grant canon in which he added the callous, caddish, and unavailable to his many masks. He followed this with Paul and Chris Weitz’s About a Boy (2002) and possibly his most complex performance to date as Will — the rich, self-regarding man-boy who belatedly matures when he takes on a fatherless kid.

Grant’s best work was during his 40s, for writer/director Marc Lawrence, opposite Sandra Bullock in Two Weeks Notice (2002) and Drew Barrymore in Music and Lyrics (2007). In both films, he is a suave fraud until something about the woman gives him courage to lower the mask and express sincerity. These movies play with the tension of what the Grant character thinks he wants — namely, a pliant partner — and what he really wants, which is an equal.

Now 56, Grant has spent most of the past decade in semi-retirement, poking up from his burrow like a groundhog to play various roles in Cloud Atlas (2012) and the failed Hollywood screenwriter in Lawrence’s The Rewrite (2014).

He declined to reprise the role of Daniel Cleaver in 2016’s Bridget Jones’s Baby, instead signing on to play the real-life St. Clair Bayfield, common-law spouse of the deluded title character in Stephen Frears’s Florence Foster Jenkins. Bayfield, a failed Shakespearean actor, tenderly assures Florence (Meryl Streep) that she is a coloratura soprano when in fact her squawk is like that of a dying hawk. Their marriage is chaste, and his affair with a younger woman causes him much shame.

Here they are — all the notes Grant has played over his career — beautifully arranged in one performance: self-hatred, tenderness, true love, deceit, and thwarted dreams. Grant’s Bayfield so profoundly connected with his screen persona — and perhaps Grant himself? — that I laughed and wept simultaneously. To watch Bayfield confess, “Once the tyranny of ambition has been thrown off, one can start to live,” is to witness Grant retrieving his supposedly nonexistent emotions. There he is, feeling and behaving at the same time.

Watch Hugh Grant and Meryl Streep talk about what they would do with an untalented costar:

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies