Why you should care about today's official plan vote

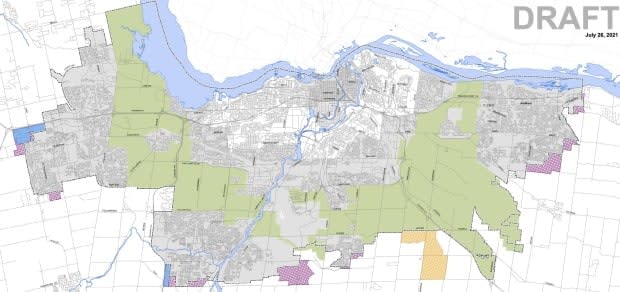

If you haven't gone through the maps in the City of Ottawa's draft new official plan, looking at areas shaded in purple and roads in thick and thin lines, perhaps you should.

They'll give you a glimpse of areas expected to be redeveloped in the future, so you'll be less surprised when several multi-storey buildings you never imagined in your neighbourhood get building permits.

The official plan being voted on at today's city council meeting will set out how Ottawa grows for the next 25 years. It's not an update — this city-building document has been written from scratch for the first time in a generation, and it aims to aggressively build up existing areas, especially those closer to downtown, to keep from spreading farther out.

More than two years of intense staff work and committee debate have led us here. The city set an overarching goal: to make Ottawa the most livable mid-size city in North America by creating neighbourhoods where residents are a 15-minute walk from groceries, schools and transit.

The plan has been tweaked a couple of times, including through dozens of motions at committee last week. More changes could be made at council.

Some dedicated residents have followed every twist and turn of these past two years and offered their own detailed suggestions.

Angela Keller-Herzog, a member of what she called a "loose-knit alliance" of groups known as the People's Official Plan, summed up their feelings this week. After all this time and work, she said the City of Ottawa's new official plan "falls short of meeting its own ambition" — and their expectations.

Fears of fast change and lost trees

Much comes down to intensification — building more units in a compact space — and how to do it.

Environmentally minded residents support compact living. They want fewer people driving, and would like to end urban sprawl altogether. Their ideal would see smaller-scale buildings where families can live in a large apartment and people can grow old in their neighbourhoods.

But what's found in the maps and documents about Ottawa's future has scared them.

Residents from the City View neighbourhood west of Merivale Road, for instance, spoke up during the three-day committee meeting, which ran nearly 30 hours and heard from 96 well-informed public delegations.

They see dots on the map for bus rapid transit stations all along Baseline Road, where nothing like that currently exists. The area is slated for taller buildings, but residents say that shouldn't come before transit upgrades have a construction date.

Such development along corridors could leave Ottawa looking more like a city of "urban canyons" instead of "urban villages," said Paul Johanis, a member of the Greenspace Alliance of Canada's Capital who has closely watched the official plan unfold.

And with all this construction, possibly the biggest concern for many residents is losing trees.

The city has set a target of 40 per cent tree canopy citywide, but that doesn't ensure a neighbourhood has shade, they say. Only last week did community advocates get traction for sub-targets for tree canopy — something to be dealt with over the next two years.

Future conflicts

City staff say change will be gradual and incremental, but many delegations have doubts. They pointed to language in the new official plan they expect developers could exploit.

The Greater Ottawa Home Builders' Association, on the other hand, finds the official plan lacking for a different reason. It argues the city has set its intensification sights too high, and won't have enough housing supply for the growing population.

That could harm home buyers, some said, and city policies could drive house prices even further out of reach.

At committee, Claridge Homes executive Neil Malhotra predicted conflicts among communities and developers will continue. He suggested how to avoid them: give each area an intensification target and let them figure out how to absorb new residents.

The People's Official Plan members agree. Planning needs to happen at the neighbourhood level, they say, and every area needs to take on population, not just older areas already under pressure like Westboro.

"We cannot plan at 30,000 feet and expect communities and developers not to end up in conflict," said Carolyn Mackenzie, a planner and member of the Glebe Community Association.

"We can't leave all this loose language in the official plan and expect us not to end up in an ongoing conflict."

Tewin risks

Given all the focus on intensification as the counterbalance to expanding suburbia, the future Tewin community "sticks out like a sore thumb," as one public delegation put it this month.

Today's vote could cement a controversial decision from last winter, when council expanded the urban boundary to include 445 hectares in the rural southeast in the name of reconciliation and economic development for the Algonquins of Ontario (AOO).

You'll find Tewin on yet another map, shown in orange on lands mostly owned by the AOO and its developer partner Taggart Group. Their vision is to create a new sustainable community for thousands of people based on "Algonquin place making."

Many Algonquin leaders still strongly object to the AOO and their plans, however. Savanna McGregor, the acting grand chief of the Algonquin Anishinabe Nation Tribal Council, wrote the mayor and all councillors yesterday, telling them to take Tewin off the table.

She said they had not been properly consulted, and Tewin "could be a very costly mistake on many fronts."

A new suburb will require water, sewers, roads, transit, community centres and garbage collection, far from existing infrastructure.

City staff have begun writing a memorandum of understanding so Taggart and the AOO pay for certain infrastructure, but the People's Official Plan wants an independent analysis of the liability the city could face — and say council can't just turn the negotiation over to staff today if infrastructure could end up costing billions of dollars.

"This one risk stands out above all the others," said Keller-Herzog.

Councillors Riley Brockington and Rawlson King agree there is simply too little information of both the costs and the climate change impacts of growing that direction, and plan to table a motion to do as the Algonquin chiefs have asked and remove Tewin. They would re-insert lands in South March for future expansion.

It's been a long road already, and today won't be the end of it. The provincial minister for municipalities, Steve Clark, has to give the final OK on the new official plan.

Then comes a giant, detailed zoning exercise, and councillors already plan to turn to it — tomorrow.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies