Why Britain really can't afford to cut civil servants right now

A letter leaked to the BBC has revealed that the UK government aims to cut up to 91,000 civil service jobs over the next three years to save money. The letter, sent to civil servants by Simon Case, the cabinet secretary, sets out the aim of reducing staffing levels back to where they were in 2016. Pay and recruitment freezes are also on the table.

This is a bad idea because of a relatively little-noticed development in UK politics which has occurred over the past quarter of a century – the deterioration in the quality and effectiveness of the British government. We know that this has happened thanks to data collected by the World Bank, which regularly publishes something called the worldwide governance indicators.

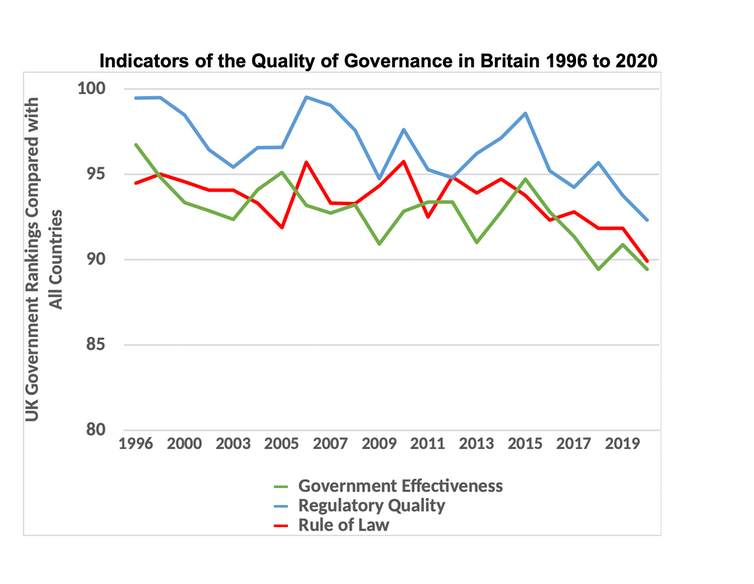

Quality of Governance in Britain – 1996 to 2020

The chart shows the rankings of Britain in comparison with other countries on three indicators: “government effectiveness”, “regulatory quality” and the “rule of law”. There are other measures in the dataset linked to political participation and freedom of speech, but these are the closest to measuring government performance.

The data, which has been gathered since 1996, summarises the views of a large number of experts, businesses and citizens about the quality of governance in their countries.

The government effectiveness category looks at what they think about the quality of the public service in their nation. That includes whether they see civil servants as independent or subject to too much political pressure. Regulatory quality is defined as the extent to which they think the government sets sound policies and regulations that enable the private sector to thrive.

The rule of law category looks at confidence in, and adherence to, “the rules of society” – including property rights, the police and the courts and perceptions of crime and violence.

Year-to-year changes in the indicators are not that large so the data needs to be examined over a long period of time. When looked at over a quarter of a century they reveal a lot about the governance of contemporary Britain. The indicators have all deteriorated over time. Britain has lost ground in comparison with the rest of the world.

Cutting jobs on the proposed scale would only make sense if one could argue that more means worse when it comes to employing civil servants. It is worth remembering that the civil service contains many low-paid workers who have direct contact with the public. They deliver benefits, provide security, work on planning applications and a host of other activities which make public services actually work. A reduction in staff on this scale is bound to damage the delivery of these vital public services, and accelerate the trends seen in the figure.

In 1996 Britain scored 97 out of a possible 100 in the government effectiveness scale but by 2020 it scored 89. In these data a high score means an effective government, with Switzerland at the top with a score of 99 in 2020, so Britain fell in comparison with other countries. It also fell in the scores for the quality of regulation from 99 in 1996 to 92 in 2020. When it came to the rule of law, Britain dropped from 95 to 90. Clearly, Britain is a lot better off in relation to governance than many other countries but the trends are nonetheless downwards.

Trouble ahead

This issue has been overlooked because it is a slow development in the background of contemporary politics, but it could reach a tipping point in which a combination of redundancies, hiring freezes and low pay creates a crisis for civil service recruitment and retention.

There are many factors which contribute to explaining Britain’s slide in the rankings, including the growing number of democracies in the early part of the 21st century (which has since been reversed). Poverty has also been reduced globally in this period and improvements in governance have been made in other countries, often assisted by international organisations. But the quality of the civil service which delivers policies is key in Britain’s current position.

According to Office for National Statistics, wage increases in the private sector were higher in 2021 than in the public sector as the economy started to recover from the pandemic. So the civil service appears to be facing bigger wage cuts in real terms at a time of growing inflation than the private sector. This is an additional disincentive to work in the public sector. In these circumstances the ability of governments to deliver on their promises is likely to be severely restricted. We are unlikely to get the best people serving the public in these circumstances.

The civil service is there to deliver government policies. But anyone who looks at the World Bank data is bound to question if the plans to make drastic cuts and reduce real wages in the service are a harbinger of blunders ahead. In their book The Blunders of our Governments, political scientists Tony King and Ivor Crewe describe how when the civil service is understaffed and underfunded, mistakes are made that ruin lives and bring down governments – from school funding to pensions to tax.

A mass cut to the civil service can result in wasted resources and poor delivery. If this turns out to be the case at a time when people are in need and finances are already stretched, then it is not a winning campaign strategy in a future general election.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Paul Whiteley receives funding from the British Academy and the Economic and Social Research Council

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies