'We're not leaving': How Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy and Black press pushed to integrate MLB during 1930s and 1940s

In February for Black History Month, USA TODAY Sports is publishing the series "28 Black Stories in 28 Days." We examine the issues, challenges and opportunities Black athletes and sports officials continue to face after the nation’s reckoning on race following the murder of George Floyd in 2020. This is the third installment of the series.

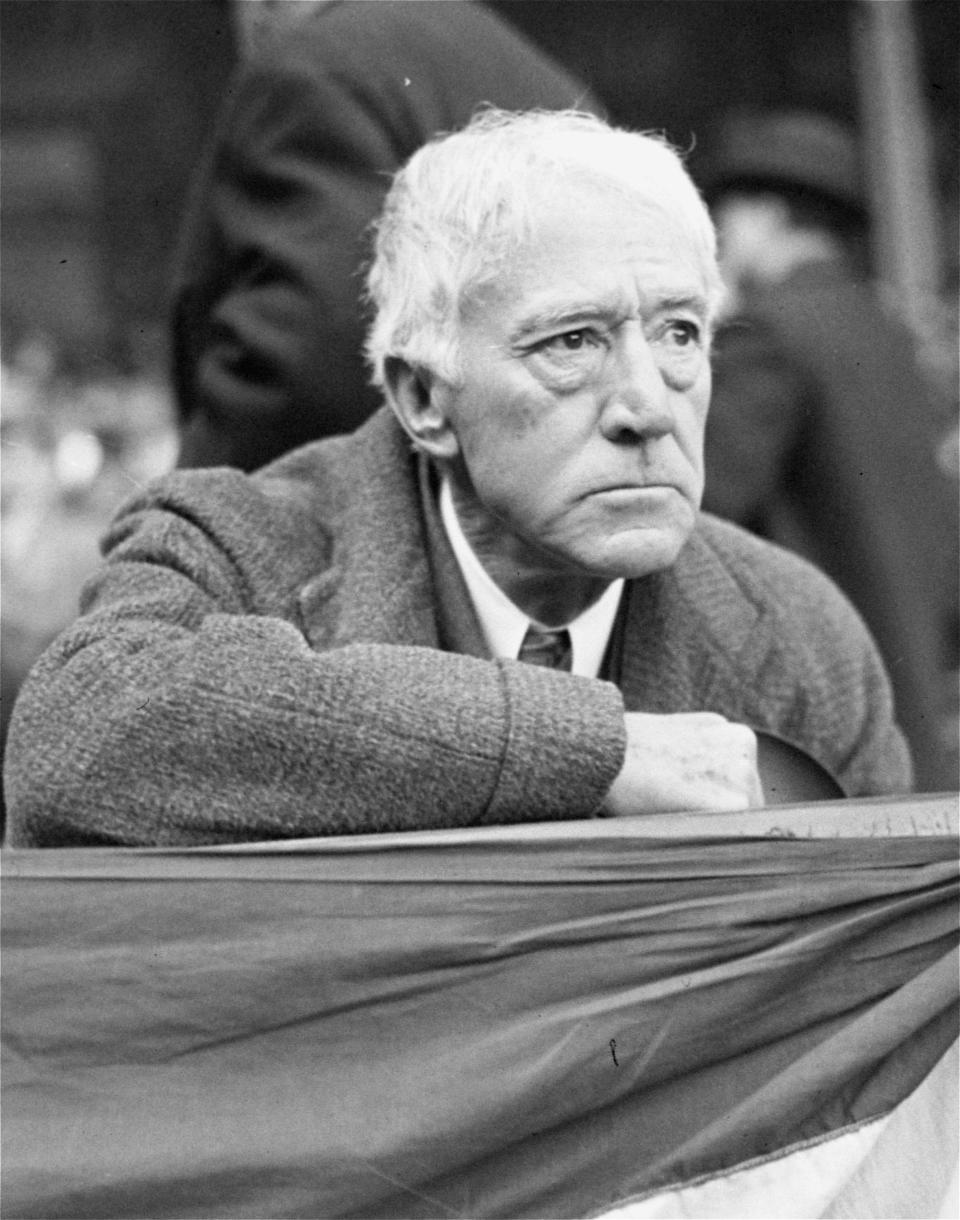

Gathered in Room O at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis called to order the Major League Baseball owners meeting on the morning of Dec. 3, 1943.

Baseball's commissioner had agreed to grant an audience to representatives of the country's Black press to make their case for integrating the sport.

Their presentation was the culmination of months of efforts led by Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro-American, but Lacy "wasn't even allowed in the room during the meeting" Chris Lamb, author of the 2012 book, "Conspiracy of Silence: Sportswriters and the Long Campaign to Desegregate Baseball" told USA TODAY Sports.

Instead, to Lacy's chagrin, Paul Robeson, a former athlete turned bass-baritone singer and actor who also was famous for visiting the Soviet Union, was there at the commissioner's invitation.

"I think it was one of those classic episodes of trying to find a way to divide and conquer," Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, told USA TODAY Sports. "You get these two Black folks who have, I guess, alternative opinions about things, to try to justify your position."

Lobbying for integration at MLB owners meeting

Landis opened the meeting by explaining Robeson's presence, while reiterating his long-stated stance on the so-called "Gentlemen's Agreement" that had excluded Blacks from "organized baseball" since the 1880s.

"I brought him (Robeson) here on my own invitation ... because this man has sense, and this man has not been fooled by the propaganda that there is an agreement in this crowd of men to bar Negros from baseball," Landis said, according to the minutes of the meeting. "So far as I know, and from all I have learned in 23 years, there is no such agreement."

STAY UP-TO-DATE: Subscribe to our Sports newsletter now!

With that, Landis opened the floor, first to Robeson, a former All-America football player at Rutgers who had also played football professionally, to speak in support of integration.

"Robeson was one of the best known Blacks in America but he was also – if he wasn't a Communist, he had Communist sympathies – and Landis wanted to paint the effort to integrate baseball as a Communist front because that would certainly be one way to kill it," said Lamb, chair of journalism and public relations at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis.

"It just pissed the hell out of Sam Lacy because Sam had worked really hard as far as setting up this meeting."

Lacy, Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier, Fay Young of the Chicago Defender and Joe Bostic of the People's Voice, were among the Black sports writers who had been vigorously advocating for baseball integration for years.

Their efforts through columns, letters and the setting up of tryouts for Black players eventually helped bring down baseball's color barrier in 1947.

"I think Wendell Smith No. 1 and Sam Lacy No. 2," Lamb said when asked to rank which members of the Black press were most instrumental. "Wendell Smith was dogged, and he was pretty emotional. He was a good reporter. He wasn't quite the writer that Sam Lacy was. And Sam Lacy was more like a lawyer. He would just sort of pick apart the arguments (against integration).

"Sam Lacy is confrontational in the same way that Wendell Smith is, basically where white owners would tap Black sports writers on the head ... and send them on their way, Smith and Lacy would say, 'We're not leaving.' "

Early efforts by the Black press

As early as the mid-1920s, Young, often referred to as the "Dean of Negro sports writers," was calling out baseball's color barrier, writing that the ban was "silly ... and should be removed."

Pittsburgh Courier sports editor Chester Washington, who in 1933 conducted a four-month "Big League Symposium" to gauge the opinions of people in baseball toward integration, sent a telegram to Pittsburgh Pirates manager Pie Traynor in 1937 lobbying him to sign players for Pittsburgh's Negro league teams:

KNOW YOUR CLUB NEEDS PLAYERS STOP HAVE ANSWERS TO YOUR PRAYERS RIGHT IN HERE IN PITTSBURGH STOP JOSH GIBSON CATCHER BUCK LEONARD FIRST BASEMAN AND RAY BROWN PITCHERS (sic) OF HOMESTEAD GRAYS AND SATCHELL (sic) PAIGE PITCHER AND COOL PAPA BELL OUTFIELDER OF PITTSBURGH CRAWFORDS ALL AVAILABLE AT REASONABLE FIGURES STOP WOULD MAKE PIRATES FORMIDALBE PENNANT CONTENDERS

When Smith joined the Courier in 1938, his first column criticized Black fans for supporting MLB teams instead of Negro league clubs.

"With our noses high and our hands in our pockets, squeezing the same dollar that we hand out to the white players, we walk past their (Negro league) ball parks and go to the major league games," he wrote in a May 14, 1938 column. "Nuts – that's what we are. Just plain nuts!"

The next year, Smith wrote a series of articles entitled "What Big Leaguers Think of Negro Baseball Players," in which he talked to 40 players and eight managers at the Schenley Hotel, near the Pirates' Forbes Field.

"Smith interviews about 50 white players," Lamb said, "and most of them say, 'No, we don't have a problem with it (integration) at all.' "

The role of the Communist Daily Worker

Although it was not part of the Black press, Communist newspaper the Daily Worker, also played a crucial role. Spearheaded by sports writer Lester Rodney, the Daily Worker began its campaign to integrate baseball in 1936.

Rodney's columns penetrated white America – in a way in a way those by Smith and Lacy could not – rallying labor unions and progressive politicians to the cause while increasing pressure on Landis and the baseball establishment.

"I think it was in many ways certainly just as important, perhaps even more important because what the Daily Worker's position created – Lester Rodney had kind of created this dialogue that was just kind of reverberating through the white community," Kendrick said. "Because when you go back and look at it, it wasn't Black fans protesting against Major League Baseball, it was white fans protesting that baseball needed to change its hiring practices."

In 1941, Rodney started sending telegrams to major league teams owners asking them to give tryouts to Black players.

According to his Society for American Baseball Research biography, Rodney said the only positive response he received came from Pirates owner William Benswanger, who agreed to arrange a tryout the following spring for Roy Campanella, Dave Barnhill and Sammy Hughes.

"Then Benswanger came under intense pressure" Rodney said for an article in "The National Pastime" in 1999, "and he backed out as gracefully as he could."

In 1942, Lester quoted Leo Durocher as saying he would sign a Black player if he were allowed to, prompting Landis to summon the Brooklyn Dodgers manager to Chicago.

After their meeting, Landis said Durocher had denied saying Black players were barred from the majors, and said he had told Durocher "that there was no rule, formal or informal, or any understanding, unwritten, subterranean or sub-anything" against signing Black players.

"A manager," Landis said, "can have one or 25 Negroes if he cares to."

Kenesaw Mountain Landis' complicity in segregation

Ahead of the 1943 owners meeting, the Black press, members of the U.S. Congress and organizations such as the United Furniture Workers, Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), the National Urban League and the NAACP peppered Landis with correspondence urging baseball to consider integration.

At that meeting, the delegation of John Stengstacke, president of the Negro Newspaper Publishers Association; Ira Lewis, publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier; and Howard Murphy, secretary of the NNPA made its presentation.

Sengstacke framed the issue of integration squarely within the context of America's ongoing fight for democracy in World War II, saying the "practice of exclusion against some players because of their color helps spread the 'master race' theory among Americans on a mass basis" and that "the forces of hate, at home and abroad, are hard at work."

Lewis pointed to the participation of Black athletes in college sports, as well as in professional boxing, basketball and football. But when the publisher of the Courier referenced Landis' earlier statement about "no written law barring Negro players," Landis immediately interrupted to accuse Lewis of misquoting him.

"I went beyond that," Landis said. "I say there is no written rule; there never has been. There is no verbal rule; there never has been. There is no haymow rule or subterranean rule or understanding, express or implied, between leagues or between any two clubs of any league."

And after Murphy outlined four specific actions to integrate baseball, Landis turned to the owners.

"Has anybody any questions?"

The silence was deafening.

Landis further showed his true feelings by appearing to castigate Smith, although not by name.

"It has been a very complete presentation of the question," Landis told Sengstacke, "although your colleague, this Pittsburgh Courier fellow, can't get it out of his hide," eliciting laughter from the owners.

"It was going to be a fixed poker game," Lamb said. "He (Landis) was a pretty shrewd guy. He was a rotten SOB and his fingerprints are all over the segregation of baseball. So, what he did, it looked like the newspaper editors were going to have their say, but he told the owners ‘Don’t ask any questions. Let’s listen to them and let’s get them out of the room as quickly as we can, so it appears that we’re taking this issue seriously, but we’re really not.' "

Major league teams allow tryouts

Although the meeting with Landis and the owners did not lead to any progress, it did not stop Black writers from continuing their campaigns for integration.

Those efforts only increased after Landis, the man the Black press disdainfully called "the Great White Father", died at age 78 of a coronary thrombosis on Nov. 25, 1944.

The following year saw a spate of tryouts for Black players – some more legitimate than others.

In April 1945, Bostic showed up at the Dodgers' training camp in Bear Mountain, New York, with Negro league players Terris McDuffie and Dave "Showboat" Thomas to demand a tryout. Although Dodgers president Branch Rickey did not appreciate being pressured to do it, he granted the players a tryout on April 7.

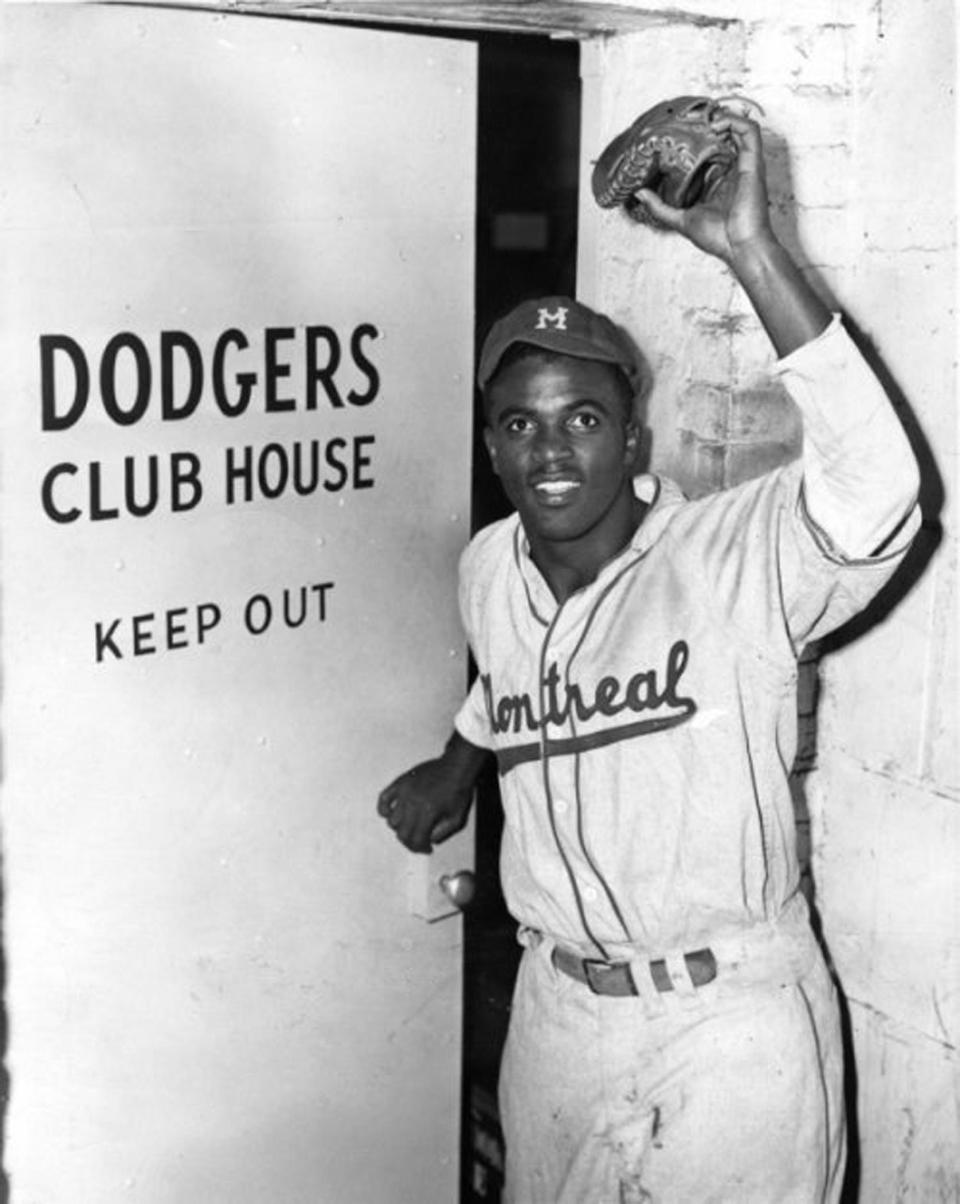

Under pressure from Smith and Isadore Muchnick, a white Boston city councilman, the Red Sox granted Negro leaguers Jackie Robinson, Sam Jethroe and Marvin Williams a tryout on April 16 after putting the trio off for almost a week.

"Everything like that (tryouts) creates publicity," Lamb said. "And as long as there are reporters who write about it, then it gets the word out and people that are reading it are saying, ‘Oh, yeah, I wonder why there weren’t any (Black players in the majors). They begin questioning and the word sort of gets out, so at the very least, these attempts were good at publicizing it. And if you’re trying to bring change on a significant level, you need publicity."

On May 7, Rickey announced plans to form the United States Negro Baseball League with six Black teams, including his own Brooklyn Brown Dodgers team. In attendance for the announcement, Smith was skeptical.

Turned out Rickey's new league was a ruse so he could easily scout Black players. He pulled aside Smith and asked him to recommend a Black player capable of playing in the majors. Smith recommended Robinson.

Partnership between Branch Rickey, Wendell Smith

Elected to replace Landis as commissioner on April 24, 1945, "Happy" Chandler officially took office a week after Rickey signed Robinson to a contract on Oct. 23, 1945.

The following year, a then-secret 25-page report submitted to MLB owners by a special committee in August 1946 defended baseball's color barrier and argued against integrating MLB.

Chandler chose not to intervene in Rickey's plan for elevating Robinson to the majors.

"The same power that Landis installed for himself when he was ruling over the (1919) Black Sox scandal, which basically gave him autonomy to overturn the owners' vote, would become the same thing that ultimately bites Major League Baseball in the emphasis of trying to keep Blacks out of Major League Baseball when Chandler becomes the new commissioner," Kendrick said. "He basically used the same power to overturn the owners' vote and allowed Jackie to play."

Once Robinson joined the Dodgers' Triple-A farm team, the Montreal Royals, for spring training in 1946, Wendell once again played an integral role, serving as Robinson's mentor and travel agent in 1946 and 1947 – while being paid by Rickey.

"He’s on the (Dodgers') payroll," Lamb said. "I’m not sure what the code of ethics with journalism would think of that, but he got – Rickey as cheap as he was – matched Wendell Smith’s salary during spring training in 1946. He became Robinson’s ghost writer and conscience and father confessor and all these things."

Robinson debuted with the Dodgers on April 15, 1947, becoming the first African American player in the majors since Moses "Fleetwood" Walker in 1884, and MLB integration would eventually spell the demise of the Negro leagues.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: How Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, Black press pushed to integrate baseball

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies