Ways of Seeing at 50: how John Berger’s radical TV series changed our view of art

It was an unlikely choice for BBC Two to schedule against Match of the Day. But Berger’s series and book now forms the bedrock of how we interpret art and advertising

On 2 January 1972, the Sunday Times ran a short preview for a new documentary. “If you are in the least interested in art,” it began, “have your set tuned and be ready to have your eyes opened by John Berger in the first of a stunning new series.” Ways of Seeing was broadcast on BBC Two at the unpromising hour of 10.05pm on a Saturday night, the same time as Match of the Day. It had a modest audience and few reviews, and yet the anonymous critic was right. This idiosyncratic documentary, made on a shoestring budget, has been snapping eyes open for half a century.

Ways of Seeing has inspired generations of writers, artists and curators, spawning academic conferences and tribute programmes. According to the novelist Ali Smith, who watched it as a child, “even its title set me on a road where I knew there wasn’t just seeing, there were … ways of it”. It reached a new tranche of readers last year by way of the American model Emily Ratajkowski, who opened her memoir My Body with Berger’s quote: “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure.”

Related: Revisited: Emily Ratajkowski’s body – and what she wants to make of it

From the very first scene, in which Berger takes a knife to a Botticelli, it was clear that Ways of Seeing was an assault on thoughtless reverence. He used the European tradition of oil painting as a way of investigating political ideology, unearthing damning evidence of an entrenched and exploitative system in the lovely works of Caravaggio and Leonardo da Vinci. One of the reasons the series is so lastingly influential is that Berger empowers the viewer, transforming them from passive consumer of high culture to detective, stalking venerated artefacts in search of the master key to patriarchal capitalism.

These paintings, he told his audience, might look beautiful or eternal, but they were actually produced for the wealthy and well born, to celebrate and solemnise their status. A landscape was not innocent, and nor was a lobster, let alone a nude of Venus. All were commodities. It was their ownership that was being exalted, and not their intrinsic existence. As for the dry-as-dust interpretations in museums, these were designed to mystify the ordinary viewer, lest they grasp the sleight of hand that had been performed.

Berger wanted to break those chains, and to do so he performed an enchantment of his own. By 1972, Berger was a well-known, often controversial art critic, novelist and broadcaster, then in his mid-40s. For minutes at a time, he stands alone against a blue screen, talking urgently and persuasively into the camera. With his curly hair and chainmail shirt, he looks like a cross between Patrick Swayze and Jim Henson’s StoryTeller, the charisma of his preaching style sitting a little uneasily with the trenchant message of demystification.

The counterpoint is a parade of images constructed by the director Mike Dibb, which build a perhaps more subtle argument. The camera ticks between famous paintings (filmed after hours in the National Gallery) and images of real life, discovering often startling parallels. In the episode on the nude, it jumps from pinups and street footage of actual women to classical beauties by Titian, Ingres and Cranach, demonstrating how women are trained to become the passive object of the male gaze. It was this argument that Ratajkowski found so compelling, although not everyone at the time appreciated the politicised argument. Clive James wrote to the Listener, complaining about “Mr Berger’s attempt to redeem the western artistic tradition for Women’s Liberation”.

Berger himself later explained that he was drawing on the pre-existing work of feminists, although he could certainly have made this clearer. In the second half of the nudes episode a group of five women politely discuss their reactions to his film. None are formally introduced, although their names are given in the credits. Most were deeply involved in the nascent second-wave feminist movement. One was Eva Figes, whose 1970 book Patriarchal Attitudes is an undoubted precedent, while the articulate woman in glasses is Jane Kenrick, one of five who had just been on trial for protesting against the 1970 Miss World contest. An academic and activist for workers’ rights, she died in 1988 at the age of 42. Her work should not be forgotten.

Ways of Seeing carried electrifying new ideas into the mainstream

Other inspirations are more carefully attributed. The first episode is a reworking of Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, which had only recently been translated into English. What Ways of Seeing really did was act as a vessel for carrying these electrifying new ideas into the mainstream. It is inevitably described as influential, but perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it arrived right on time, conveying a new attitude or approach to culture that would soon be dispersed globally, in post-colonial, queer and feminist studies, in Marxist readings of Jane Eyre, in media studies classes, and art school reading lists.

Related: John Berger: ‘If I’m a storyteller it’s because I listen’

The same cannot be said for how it was made. Ways of Seeing represents a zenith of creative freedom at the BBC, only glimpsed now in the work of Adam Curtis, which likewise combines a seemingly radical message with an oddly didactic narrator. Berger might have been the face of the series, as well as the better-known partner, but the process of making the series was unusually collaborative. It was one of Dibb’s early outings as a director, and interference from above was nonexistent.

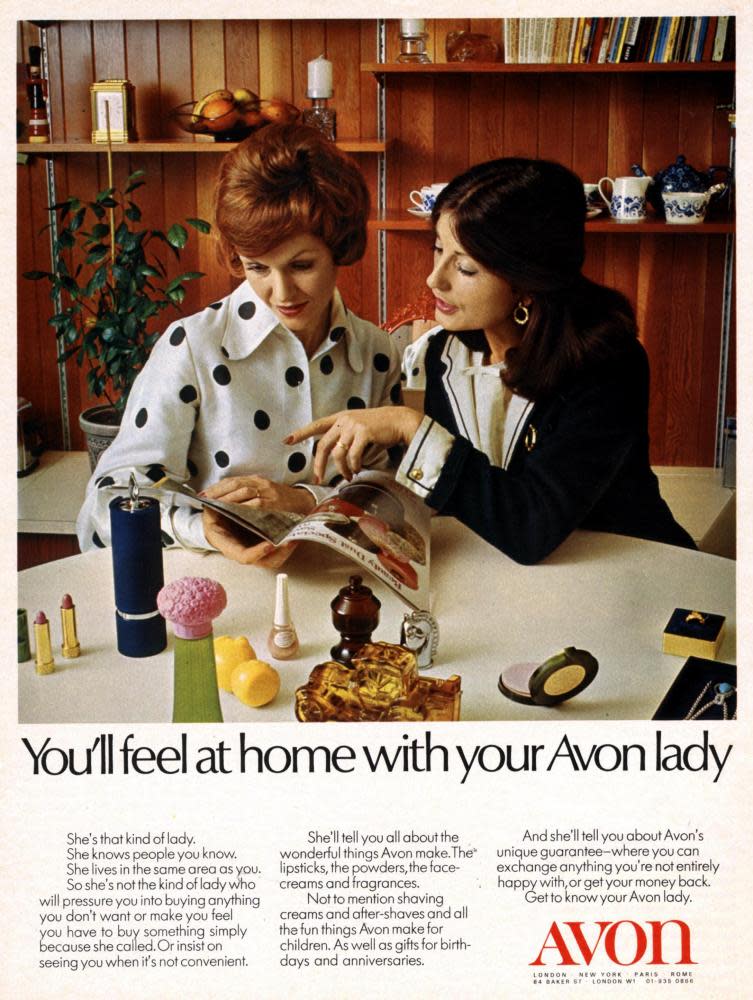

Berger had already abandoned England for a farm in the Alps, and draft scripts were posted back and forth for months. The subject for the final episode was not decided until well into the shoot, when Berger became fascinated with adverts during a journey by tube. This risky, on-the-hoof way of working, with its sense of experiment and fresh discovery, is what gives each episode its fizzing energy. The BBC’s electronic music pioneer Delia Derbyshire provided the ambiguous, open-ended soundtrack, enchanting Dibb with her habit of taking snuff as they worked.

But how did Ways of Seeing actually get seen? Broadcast in the pre-VCR, pre-digital age, the programme itself was swiftly inaccessible. It was repeated once in 1973, after winning a Bafta, but was not screened again until 30 July 1994. Unless you had resorted to that new technology the video recorder, as some prescient teachers did, it was the companion book that gave Ways of Seeing its longevity. Lifetime sales in the UK alone currently stand at 1.5m, making it one of the most widely read books on art ever published.

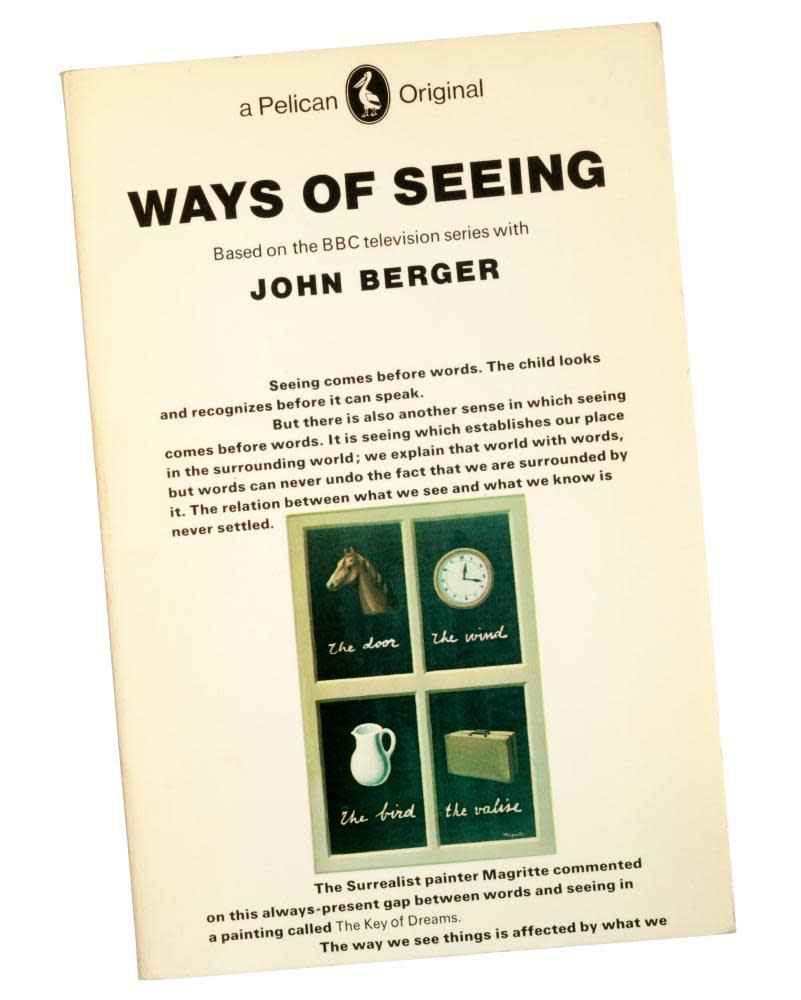

The first edition cost 60p. “We wanted it to be the cheapest art book ever made,” Dibb says. “We tried to do everything an art book didn’t do.” Although it’s often treated as a purely Berger production, it was also a collaboration, this time with a team of five. The graphic designer Richard Hollis was responsible for the book’s distinctive appearance, including putting the first six and a half sentences on the cover, alongside a painting by Magritte. The text itself, printed in eye-bending bold type, was a smoothed and tightened version of the film’s script.

Both versions represent the echt Berger style: at once poetic and didactic, fluid and rigid. Sternly, he points out the wicked ideologies locked into paint, the grotesque display of capitalism, profit, property in Gainsborough’s Mr and Mrs Andrews and Holbein’s The Ambassadors. Swooningly, he shows how the light falls in a Vermeer. Sometimes it is as if two people are talking, and in fact Berger was at a crossroads in his own work. As Ways of Seeing carried theory into the world, he moved away from it, consecrating himself to an artist’s take on politics and not a political take on art.

Part of what makes watching it so compelling now is Berger’s fascinated immersion in the culture of images itself. Take a single shot from episode two. Against a closeup of dresses in shining pink and sea-foam green, we hear his dreaming voice say: “The faces of the women in so many European paintings are like the faces of swimmers in seas of silk and satin.” No other critic had that kind of loving, estranging vision, the capacity to see the grid of forces in which we are entrapped while still conveying the ravishing, time-stopping power of paint.

If its style of analysis has become commonplace, Ways of Seeing retains a capacity to stun new viewers with its revelations, although these days the wealthy are more likely to invest their money in NFTs than Rembrandts. The most relevant episode for our own digital era is the last, on the imagery of advertising. Berger reveals a dreamworld that we all move through continuously, a visual bombardment designed to conjure deep feelings of inadequacy and desire, the long seduction by capitalism upon its hapless subjects.

This spell has only grown more powerful in the intervening decades. These days we inhabit a universe of disembodied images, constructed by mysterious forces we can’t quite glimpse or understand. Berger identified that process of mystification and knew it as the pickpocket’s device. To break it begins with understanding what you see, and realising that seeing is an active choice. Art is not separate. It is part of how reality is built – or for that matter made anew.

Olivia Laing’s latest book is Everybody: A Book About Freedom.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies