Unpacking the wild twists, excessive vomit in 'Triangle of Sadness': 'Maybe it was too much'

Spoiler alert: The following interview addresses plot twists and details of "Triangle of Sadness," including the ending.

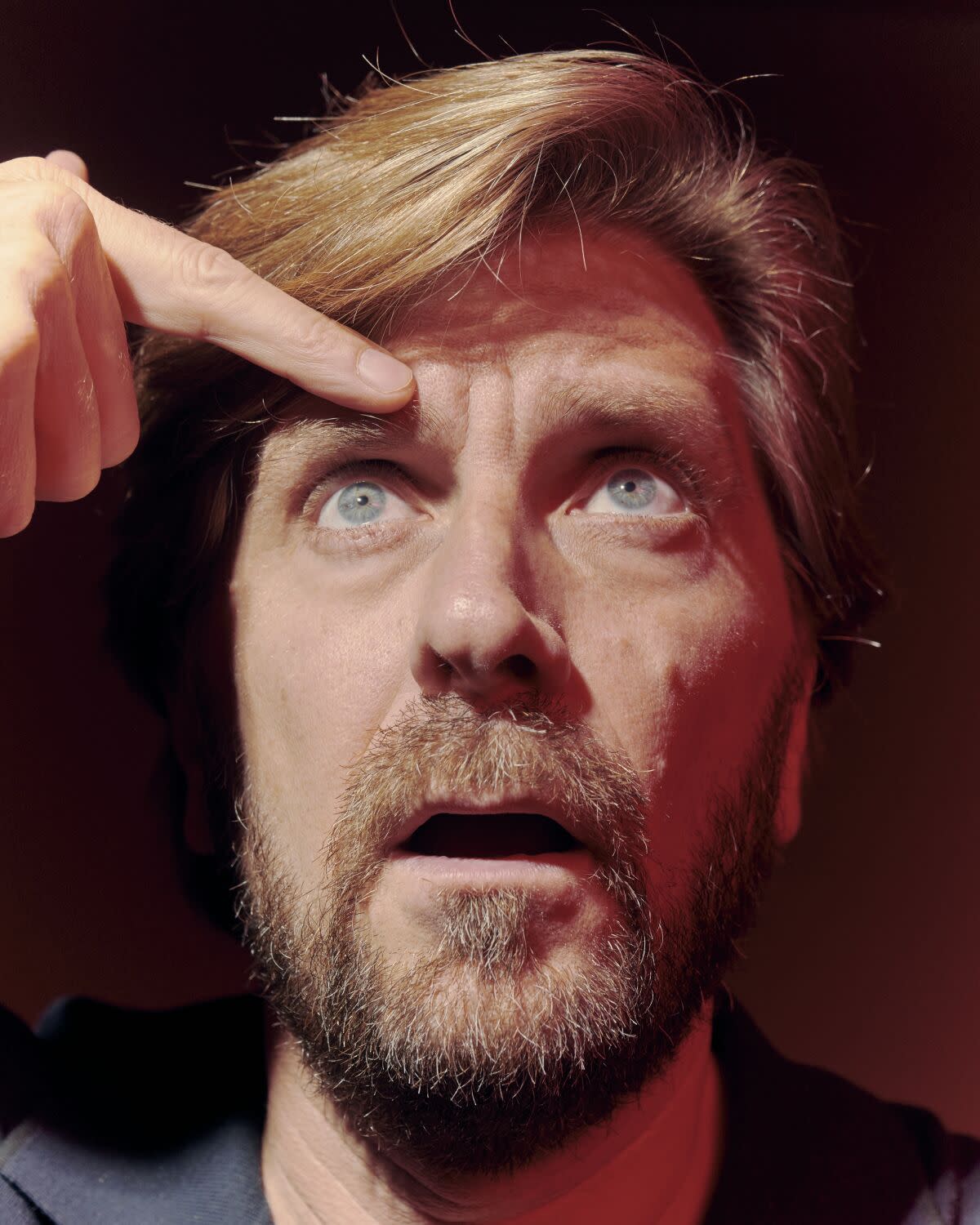

When Swedish filmmaker Ruben Östlund won the top prize at this year’s Cannes Film Festival for “Triangle of Sadness,” it put him in the rarefied class of two-time Palme d’Or winners. The prestigious group also includes Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Haneke, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, Emir Kusturica, Shohei Imamura, Bille August, Alf Sjöberg and Ken Loach.

But none of those titans of international cinema ever won for a film with an outrageously extended sequence of passengers aboard a luxury yacht violently vomiting and soiling themselves during a storm at sea. Östlund, 48, prides himself on upending the traditions of upscale art cinema, creating biting social satires in his previous films, “Force Majeure” and the Palme d'Or-winning “The Square,” with surgical precision. Taken together, they compose an informal trilogy on privilege and contemporary male anxiety. But besides being trenchant examinations of modern life, his movies are also very fun.

In “Triangle of Sadness” — the title refers to the area at the top of the nose and between the eyebrows, often fixed with Botox — male model Carl (Harris Dickinson), insecure about the financial success of his model/influencer girlfriend, Yaya (Charlbi Dean), accompanies her aboard a luxury yacht with a drunken Marxist captain (Woody Harrelson). When a violent storm causes all the guests to become extremely seasick and the ship itself to crash, a group of survivors land on a seemingly deserted island. That's where Abigail (Dolly de Leon), a cleaning woman from the ship, suddenly assumes an increasingly tyrannical leadership position thanks to her practical skills, such as knowing how to start a fire.

Following the film's Cannes success, unexpected tragedy struck in August when the South African-born Dean died at age 32 in New York City from a sudden illness. Östlund addressed paying tribute to Dean as he sat for an interview at the recent Toronto International Film Festival in the kind of luxury hotel restaurant his movies might very well upbraid.

I can’t even imagine how difficult it must be to promote the film following the death of Charlbi Dean. The timing of that must have come as such a shock.

I was in contact with her a few days before, and all of us, the ensemble, were planning to go together to Toronto and to the different premieres. And basically I was woken up by a text ... first you didn't believe it was a hundred-percent true, and it took many hours before I could confirm [it was]. Of course then the most sad thing is Charlbi was a great colleague. She was a team player, she was lifting up everybody around her, and you could really feel that on set. She was looking forward so much for the premiere of the film in the States or in Canada. And we had a great time in Cannes. It was like a feeling of this was her time, and maybe a new direction of her career.

It's always a tragedy when someone is young and dies, it came very sudden and it's going to feel a little empty when she's not there next to us. For me, it's important to go into this work in the same way I would have done if she was next to me, because it's also a way for me to pay tribute to her, to her work and to her legacy. But I definitely think that the people in the cast felt it was a little bit hard to talk about the film.

And as a way to start talking about the movie, can you discuss the structure? What made you want to have the three distinct sections to the movie — opening with Carl and Yaya, moving onto the yacht and then on the island?

I knew from the beginning that I wanted the film to be about beauty as a currency. This came out of discussions I had with my wife, she's a fashion photographer, and she had told me so many interesting stories about how the models often come from very different parts of society. All of a sudden they are pushed up in society, and they get used to a certain kind of lifestyle and go on these trips everywhere. But the career is very, very short, so what should they do afterwards? Should they go back to being a car mechanic, like the inspiration for the character of Carl — that model worked as a car mechanic, and all of a sudden he became one of the best-paid models in the world. There's something absurd with this, to rely on your beauty as currency.

That was the starting point of the idea [and then the models] go to a luxury yacht, where many of these people maybe don't have access to that world if it wasn't because of their currency. And then go to the third part of the desert island, where we take away all the previous hierarchies and we start from the bottom and know-how becomes the most important thing.

I thought that the deserted island was a great way of commenting on our times, where very few of us actually have the basic skill of how to survive [and] are so used to a certain kind of lifestyle. What happens when we take that away?

With the yacht sequence in particular, was it important that it not be so easy to reduce the film to just “rich people are awful?” Did you want it to be somehow more complicated?

Yes, definitely. But I think one thing when it comes to my films, I'm kind of mean to all of the characters. I'm not nicer to the poor than I am to the rich, I'm kind of mean to everyone. And for me, I think the reason is because I'm interested in when we are failing and when we are not succeeding in being good humans. I'm not so interested in when we succeed. I'm interested in failing as sociology — we are not pointing our fingers on the individual, we're actually pointing fingers on the context, the set-up that can create our behavior.

For me, it would be completely not interesting to show a good person succeeding in being good. We already have all these stories doing that. I want to add something ... and I want to corner the characters. That is maybe better than saying being mean or harsh. I want to corner them and put them up to deal with dilemmas: "You have two options, none of them are easy. How do you deal with it?"

I heard something interesting when I did the research of the yachts. They had a problem with the jacuzzi that they had in the master bedroom, because very often the man that stayed in the master bedroom wanted to fill up the jacuzzi with champagne. So they filled it up with champagne every time they were asked for this, but it happened quite often. They had enough when one of the passengers wanted to fill it up with champagne and goldfish. They're like, "Maybe we have to move the jacuzzi from the master bedroom." I thought it was fantastic.

They look at it from a behavioristic point of view. It just creates bad things with these passengers. They're so used to asking for whatever they want. And we are not allowed to say no, so maybe we should move the master jacuzzi.

I have to ask about the vomiting sequence, when everyone on the yacht becomes graphically sick. Obviously, the extremity of it is part of the point, but how did you decide on the right amount of too much?

From the beginning, I decided that I wanted to push it very far, so the audience would feel, “Please save them. They have had enough.” It's very hard to know how far you have pushed it because you get so used to the material yourself. So when I was sitting and editing it, I said, “This is nothing,” because I've watched it a hundred times. And then when we had the first screening of the film, I realized, “Oh s—, maybe I overdid it.” Maybe I should have been a little bit more careful. Maybe it should have been a little bit less. Maybe it was too much in the end. I apologized to the audience. But it was too late to recut the film.

It's about the dynamic of the whole film, of course. I love to push my scenes. There's so many movies that I watch where you have a great experience when you watch the film, but then after that I don't really remember it. For me, I really want to leave a mark. I want people to know, “Oh my God, this is pushing it further than I could expect.” The first version of the film was 3 hours and 45 minutes, basically with the same scenes, so the scenes were much, much longer. And then I slowly sculpt it down ... but the throw-ups, that took me half a year to edit.

Now I hope you don't mind talking a little about the ending. The film ends with a cliffhanger, whether one character will kill another, sending them back to civilization or not. What was it that made you want to leave audiences as you do?

I don't think it is important if she kills her or not. I think the important part is can we identify with the possibility of her to do it? Then if she does it or not, okay, that can randomly play out in two different ways. And I think also that I had an idea that I wanted half of the audience to want her to kill and half of the audience to say, ‘No, don't do it.’ So for me, it's not interesting what she does, but that it's possible for her to kill her.

The dilemma of the ending seems like a great distillation of your filmmaking and the sort of moral questions that you like to ask of audiences.

Yes, definitely. Every time I watch something that I have to reflect myself on how I should relate to a situation, then I get interested. And then I also start to ask questions. Basically, all my films try to confront myself with situations that I think are hard to handle.

You are now in extremely rarified company to have won the Palme d’Or at Cannes twice. What was the experience like?

To win it once was the feeling of like, "Okay, wow, I'm one of the lucky ones that actually get to experience this." We all know how hard it is to make a film that is good enough to go into competition, and when you are in competition, then to fight with the best films in order to get a prize. So I was very lucky.

The next time when we were sitting in the award ceremony and we see prize after prize go to other films — finally it's only one prize left, and I started to feel this emptiness because I started to figure out we are going to win the Palme d'Or again. I'm starting to feel, "Do I really want to go through this again?" It's a lot of work, but at the same time, like, wow, am I now in the league with Coppola and Michael Haneke and the Dardennes and it feels so normal, but I thought it would feel special? It's scary how normal it feels.

And one thing with the second Palme — I want to be humble, but you know, it is a possibility now to win a third Palme. No one has done that before. I don't want to be arrogant, but it actually is a possibility.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies