Nine British seaside hotspots and how they're changed – for better or for worse

We love our seaside towns. We must do; there are loads of them. An official government source lists 108 seaside towns in England and Wales. Wikipedia, which includes villages and suburbs with beaches, pushes the number up to 213 for the whole of the UK.

If you did the Paul Theroux thing, and travelled round the entire coast of the kingdom, you’d struggle to get further than 10 miles without bumping into a shop selling rock, a breezy prom and a murderous herring gull – until you got deep into the north of Scotland, at least.

Nostalgia, tradition, good old seaside fun and the opportunity to connect with our fellow citizens mean we preserve a special fondness for the resorts we visited in childhood and the experiences enjoyed there – and often wish to pass on. Even people who perennially go abroad for sunshine and shiver-free swimming usually have a favourite British beach bolthole they visit every so often.

Adapting to change has been crucial for many coastal towns. Others have prospered by not modifying much at all. Blackpool has evolved from a working-class Wakes Week destination into the north west’s premier LGBT resort. Margate has embraced art and exiles from expensive London. Whitby has milked the Dracula/Goth market. Others have built a smart, even exclusive brand, resisting fashions and eschewing funfairs and other artificial entertainments.

It’s become a national habit for people, including journalists – even travel ones – to write off the British seaside holiday as passé or worse. But it has a heritage as old as the Industrial Revolution, and our piers and fun palaces are still a lot livelier than our cotton mills and coal mines. We’re drawn to the edge of the land by mysterious forces and deep inner urgings. We’re also pulled there by connections, to memories, places, old photographs, to one another.

As we enter the middle of August – school holiday time, the peak of our short summer season – it’s an opportunity to flick through the diorama of days gone by and chart the highs and lows, ebbs and flows of our very special seaside.

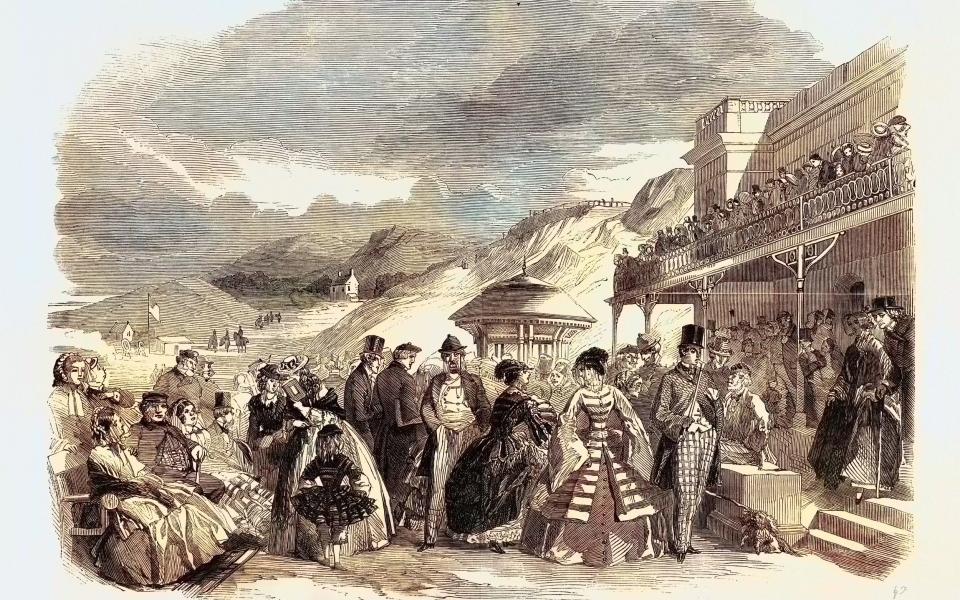

It all started in Scarborough

Where did the seaside holiday really begin? Scarborough has become the standard text, with much retelling of the story that Elizabeth Farrow, in 1626-7, discovered a stream of acidic water running down the cliff and into the sea in the South Bay. She claimed it “did both open the body and also amend the stomach”. In the 1660s, a Dr Witte published Scarborough Spa, which suggested sea water was a “Most Sovereign remedy against Hypochondriack Melancholy and Windness”. All of which is very colourful, but pertains to the drinking of freshwater, not bathing in sea water.

By the time bathing machines appeared at Scarborough, in 1735, people were taking to the sea all along the English coast. Still, Scarborough was always near the top of the pile and its Grand Hotel, completed in 1867, was once the largest in Europe. The resort helped establish the connection between health and the seaside – though in the Victorian era, many popular seaside towns had issues with effluent returning to the beach…

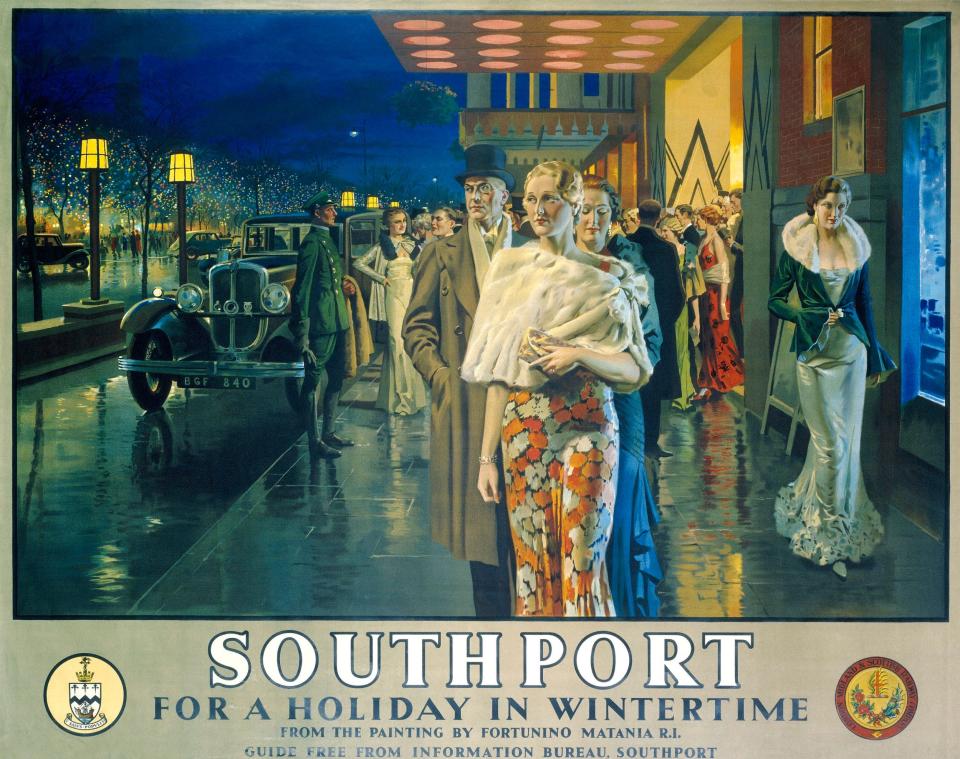

Southport: Paris of the North

The “slow travel” trend started in the 1770s, when pioneering paddlers came to Southport using the Leeds-Liverpool Canal, de-barging at the Red Lion Bridge, five miles inland, there to take a carriage or cart. Perhaps this leisurely, thoughtful approach inspired the landowners – the Heskeths, Bolds and, later, Scarisbricks – to make their resort a refined sort of place.

The beating heart here is not the prom or the beach but Lord Street, a broad, tree-lined Victorian boulevard that some claim inspired Napoleon III to rebuild Paris. Convenient for Liverpool merchants, Southport became a place of residence for the well-heeled, who endowed the town with handsome churches and civic buildings. In 1904, the 23-mile railway from Liverpool Exchange to Southport and Crossens became the country’s first electrified mainline.

Big, bold Blackpool

Blackpool evolved relatively late, but would become the most popular seaside resort in the country, if not the world. Rail connections to Preston, Manchester and beyond meant millworkers could visit for long weekends and Wakes Weeks in the latter half of the 19th century. The beach was broad, with plenty of space for fairs, entertainers, stalls and clairvoyants as well as bathing and frolicking. Three piers offered promenading options for all-comers, but the working classes soon made Blackpool their own.

Everything was industrial-scale to match, from massive hotels to vast open-air bathing pools to record-breaking funfairs. With seven million people coming to see the Tower and taste the salty air during the Thirties, only New York’s Coney Island came close in terms of visitor numbers. JB Priestley, visiting in 1933, complained its “amusements are becoming too mechanised and Americanised.”

But Blackpool – famous far beyond Lancashire for its guesthouses, trams, end-of-the-pier shows and Illuminations – is now seen as quintessentially English.

Royalty and rockers

Brighton’s growth to some extent mirrors that of the northern resorts, though it always had a social advantage due to its proximity to the capital and wealthy Sussex and Surrey. The Royal Pavilion and surrounding gardens were built as a seaside retreat for George, Prince of Wales, who became Prince Regent in 1811, and King George IV in 1820.

During the Napoleonic Wars, toffs fell back on Brighton when the Grand Tour circuit was temporarily closed. Fast trains to London created a massive daytripper market in the Victorian era. The hoi polloi found a way to holiday without bumping into proles; as seaside historian John Walton writes: “The summer became more down-market, while the more prosperous visitors shifted to the autumn and winter to avoid the Cockney contagion, where they were not lured abroad; but Brighton became the metropolis in miniature.”

Electric trams and motor buses urbanised the former fishing village, creating London-by-the-Sea, with all the fun and seediness, crime and glamour that signifies. Graham Greene’s 1938 novel Brighton Rock played on these tensions. In 1964, Mods and Rockers fought on the beach. Since then Brighton has calmed down and been somewhat gentrified up. A desirable commuter and university town and a place of exile for faded artists and pop stars, Brighton is the most successful seaside city in economic terms, and you can still walk its pebbly beaches and forget about the wider world.

Less is more in South Devon

Torquay’s mild climate and calm seas, protected by the enveloping curve of Tor Bay, has long drawn health-seekers from all over Britain. But its Winter Gardens and Opera House never really prospered, and perhaps a lesson about limiting development spread along the coast. For the real attraction of towns like Dartmouth and Kingsbridge and less populous spots such as Slapton Ley and Hope Cove is that less can be more.

Clean sandy beaches, swimmable seas, plain food and drink, a little naval history here, some birding there: these are the simple but saleable offerings of the coastline from Blackpool Sands to Wembury. For those who want a bit more action, Paignton is a traditional bucket-and-spade resort and Brixham a mix of fishing port and picturesque town.

Unusual for the British seaside, South Devon has also proven popular for more than a century with foreign travellers – partly because of the ferries, but also because German caravanners and middle-class French families don’t really want to experience anything too English.

Family fun (or else) in Skegness

Skegness was a haven town and a fishing village before the Earl of Scarborough (of all people) engaged an architect to devise a model watering place. Work began in the late 1870s and while an imprint of the grandeur of the original tree-lined throughfares, promenades and gardens has survived, the resort is now more of a funfair and fish-and-chips place.

Cleethorpes, up the coast, feels far more refined. In 1936, Billy Butlin opened his first Butlin's holiday camp at Ingoldmells, three miles north of Skegness. He’d got the idea while visiting a company-owned summer camp in Canada and had also seen the camp built by Harry Warner at Seaton in Devon. Guests were provided with accommodation, three meals a day and free entertainment. Initially there were chalets for 1,200 but eventually 10,000 holidaymakers could be accommodated.

Seeing guests were enjoying themselves and not attending camp events, Butlin got an engineer to tell jokes – he instructed him to wear a red blazer, which he’d liked the look of when he’d seen Mounties sporting them. In 1948 he opened his own airport next door handling passenger and freight charters, plus local pleasure and sightseeing trips. The first commercial monorail in the UK opened at Skegness Butlin’s in 1965.

Bugger Bognor!

The famous words “Bugger Bognor!” are attributed to a sickly King George V, when asked to bestow the title of “Regis” on the town, or when he realised no amount of sea air was going to save him from terminal decline. The words could equally be applied to the way perceptions of domestic seaside resorts hit bottom in the last quarter of the 20th century.

With the arrival of foreign holidays, wet British summers, rusty fairground rides and fusty bed and breakfasts all lost their sheen for the working classes, while the transformation of many coastal towns into retirement enclaves or last resorts for the downtrodden made the amusement arcades look sarcastic as well as past their sell-by date.

Many towns still struggle to recover, or reinvent, their historical appeal. Places like Rhyl, Rothesay, St Annes on the Sea, Pendine Sands and the Isle of Man, and many others, rely on nostalgia, old habits or on keeping prices and package deals dirt-cheap. But, as demonstrated by the likes of Southend, Great Yarmouth and Whitby, the tide can be turned and people will come back – as they did, of course, during the pandemic.

The art of coastal living in Sussex

Some established seaside towns have been revitalised by the creative arts. In the early 2000s, the Modernist De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea was granted £6 million of lottery funding for restoration work and to create a contemporary arts centre. The positive media reaction helped put the building and wider East Sussex shore on the map. An 18-mile Coastal Culture Trail now links the De La Warr with Towner Eastbourne and Hastings Contemporary galleries.

The opening of the Turner Contemporary in Margate in 2011 boosted the unfashionable Kent resort, and has helped make Margate a place to live as well as to visit. And Folkestone Artworks, featuring pieces by 46 artists in scenic and surprising locations, claims to be the largest urban outdoor exhibition of contemporary art in the UK.

The rise of Cornwall

Padstein, Mousehole, St Ives, Poldark, surfing, Carlyon Bay, Mevagissey, second homes, Dawn French, wild swimming: when is Cornwall not in the news for one reason or another? It’s hard to imagine a time when the main attractions were Land’s End and pasties, and perhaps a souvenir from Jamaica Inn. There have been holidaymakers here since the 19th century, but the county is now reliant on tourism in a way we have seen on Spain’s Costas and in places like Thailand and Cancún.

The appeal is obvious – Cornwall is far from London and from populous, post-industrial cities; it has lovely clifftop walking and attractive coves and a distinctive history. The middle-class metropolitan-based media, always on the lookout for destinations that reflect its priorities and tastes, has chosen Cornwall as its leisure canvas.

But passions and fashions change. Perhaps we have already seen peak Cornwall. The trade in tourists has done little for the regional economy, locals are in uproar about house prices due to inward migration and holiday properties, and the boss of Visit Cornwall has already talked of “staycation fatigue”.

What’s next?

Seaside towns have always boasted fortune-tellers. What is inside the crystal ball for our beach resorts, small and big, trendy or tired? Will a northern Eden Project do for Morecambe what it has done for southeast Cornwall? Will home-working make lifestyle-focused coast towns like Lytham, Southwold and Lyme Regis the ultimate beach-view boltholes?Will an ageing population make nostalgia the key selling point? Or will rising seas, fragile coastal defences and an increasingly unstable climate have us all fleeing inland and upland?

These questions are on the Government’s agenda but not anywhere near the top right now. What’s certain is that the British seaside will evolve, as it always has, but our love for the coastline will linger. There’s still life in the old donkey, the creaking big dipper, and just strolling along the prop-prom-prom, close to the sky and the sea.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies