UBC researchers find 'weak spot' in all variants of COVID-19 virus that could lead to better treatment

Researchers at the University of British Columbia (UBC) have discovered what they describe as a "weak spot" in all of the major variants of the virus that causes COVID-19 — a revelation they believe could open the door for treatments to fight current and future mutations.

In a peer-reviewed study published Thursday, the research team said they found a largely consistent soft spot — like a chink in the virus's spike protein armour — that has survived the coronavirus's mutations to date. Scientists determined a certain antibody fragment was able to "effectively neutralize" all the variants, to some degree, because it exploited the vulnerability.

"What's exciting is what it tells us we can do now. Once you know the [weak] spot, it's a bit like the gold rush analogy. We know where to go," said Sriram Subramaniam, the study's senior author and a professor with UBC's faculty of medicine.

"We can now use this information ... to design better antibodies that can then take advantage of that [weak] site."

Looking for the 'master key'

Antibodies are naturally produced by the body to fight infection, but can also be created in a laboratory to administer as treatment. Several antibody treatments already exist to fight COVID-19, but their effectiveness fades against highly mutated variants like the recently dominant Omicron.

"Antibodies attach to a virus in a very specific manner, like a key going into a lock. But when the virus mutates, the key no longer fits," Subramaniam wrote in a statement.

"We've been looking for master keys — antibodies that continue to neutralize the virus even after extensive mutations."

Subramaniam said the antibody fragment identified in the paper would be that "master key."

Matthew Miller, director of the DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont., described the findings as "a really important development" in the fight against COVID-19.

"It's been able to show that this antibody works against all of them and that's really unique. ... It certainly raises the hope that this [weak] area they're targeting would be an area the virus would have a lot of trouble changing — even going forward, because if it were easy to change, it's very likely [the virus] would have tried to change it already," Miller said in an interview Thursday.

"Now ... viruses can always trick us," he noted. "They're smart. There's always ways out. But what we want to do is make it as hard as possible to do that."

High-tech imaging used to study virus

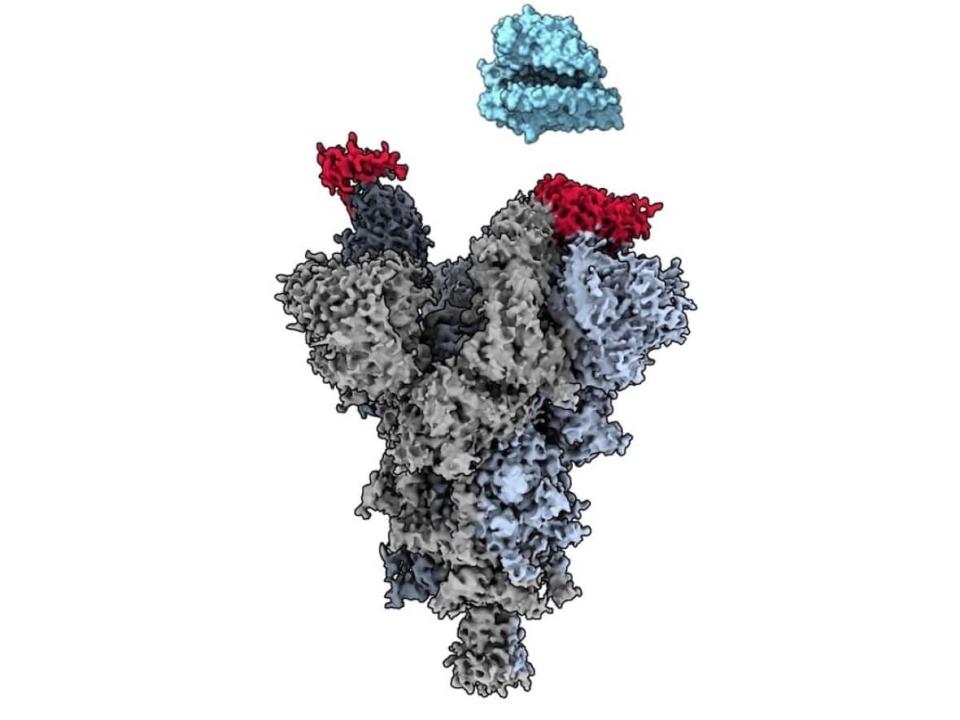

As part of the study, published in Nature Communications, the research team used a process called cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to examine the weak spot on the virus's spike protein, called an epitope.

Cryo-EM technology involves freezing samples of the virus and taking hundreds of thousands of photos — similar to X-rays — used to recreate a 3D model of the molecule from an atomic level.

"Imagine you were the size of an atom and you could watch exactly what was going on," Subramaniam explained.

Through the process, the team saw how antibodies interacted with virus. The antibody fragment, called VH Ab6, was able to latch on to the weak spot and neutralize the virus.

Subramaniam said drug companies could exploit the weakness to create a potentially "variant-resistant" treatment.

The researcher noted that developments resulting from the team's discovery won't be part of COVID-19 treatment in clinics for some time, but he described it as one more step in understanding the coronavirus itself and the illness it causes.

"We never know if this antibody will suddenly not be effective against the next variant or not. ... But we're just saying that it stood up really well to being able to neutralize the variants we've seen to date," Subramaniam said.

The UBC team collaborated with colleagues at the University of Pittsburgh, who have been screening large antibody libraries and testing their effectiveness against COVID-19.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies