Do the U.S. Navy’s Aircraft Carriers Still Rule the Seas After Nearly 100 Years?

The U.S. Navy has fielded aircraft carriers for 99 years, and today the carrier is still as important as ever.

Although carriers are extremely useful, new technologies have rendered them vulnerable.

Carriers may not be done for, but they will be forced to evolve—and innovate—to survive budgetary battles.

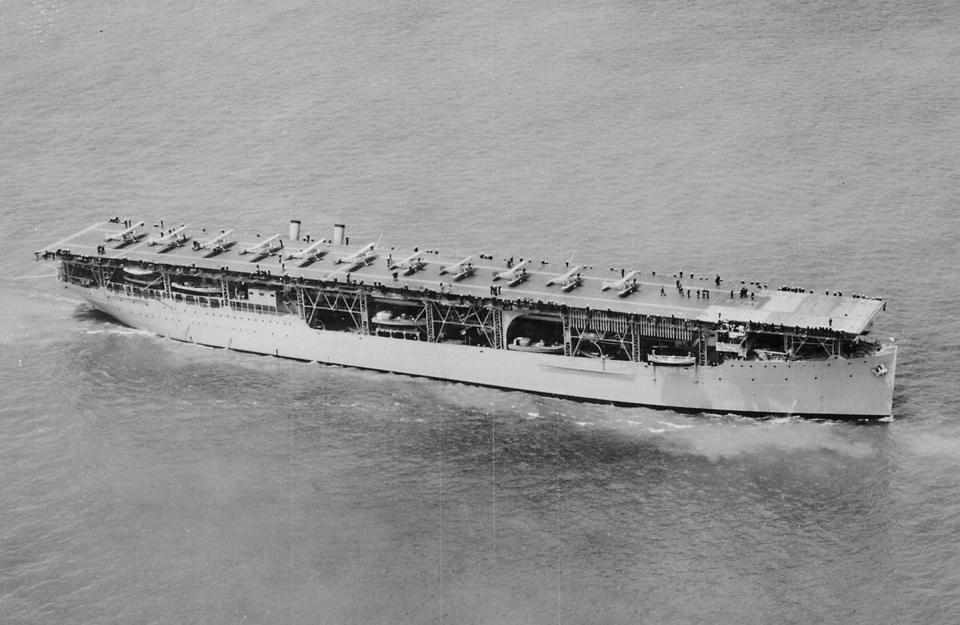

Ninety-nine years ago, the U.S. Navy commissioned one of the most unusual—and controversial—ships ever to enter the fleet. The USS Jupiter, a veteran coal transport, emerged from the shipyards at Portsmouth, Virginia, transformed into the new USS Langley, the Navy’s first true aircraft carrier.

Today, ten decades later, the carrier is still the centerpiece of the battle fleet and the service’s eleven carriers still have the same mission: project air power from the sea. But after nearly a hundred years it’s worth asking: is the aircraft carrier the most effective tool of modern seapower? And if it isn’t, could something else take its place?

The Attack of Pearl Harbor and the Ascent of the Carrier

By winter of 1941, the U.S. Navy had eight aircraft carriers, including the Langley, which amounted to the third-largest carrier fleet in the world. The attack on December 7, 1941 thrust the United States into World War II, but the Navy lost zero carriers in the attack.

In that attack, the Imperial Japanese Navy showed the U.S. how multiple carriers combined into task forces could aggregate air power, and not only defeat other fleets but also attack targets on land. The Navy, which had previously used carriers as scouts for fleets of battleships, quickly took heed of the lesson and used carriers to smash the Imperial Japanese Navy at Midway. Then, it conducted an island-hopping campaign across the Pacific that rolled back the Japanese advance.

Meanwhile, American industry went into overdrive building carriers and carrier-based fighters; just four-and-a-half years after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. boasted a massive force of 99 carriers of all types.

The aircraft carrier continued to be the dominant naval platform through the Cold War, replacing piston-powered aircraft with jet-powered ones, and U.S. carriers adopted nuclear power as a primary fuel source. Even the invention of the atom bomb didn’t end the primacy of carriers; instead, carriers became a platform for delivering thermonuclear weapons.

When the Soviet Navy dissolved at the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy carrier force shrunk and became a tool of expeditionary warfare supporting land wars with sea-based airpower. Now, in the third decade of the 21st century, new threats from Russia and China could spell the end of carriers, or force them to innovate into something new that will continue to dominate the maritime domain.

Today’s Carriers

Today, the U.S. Navy operates a fleet of 11 aircraft carriers, ten Nimitz-class carriers and a new Ford-class carrier. All eleven carriers are nuclear powered and typically embark a carrier air wing of up to 74 aircraft, including 44 F/A/-18E/F Super Hornets and F-35C Joint Strike Fighters, 5 EA-18G Growler electronic attack jets, 4 E-2 Hawkeye airborne early warning and control aircraft, two C-2 Greyhound transports, and 19 Seahawk helicopters.

A typical carrier strike group consists of one aircraft carrier with attached carrier air wing, one guided missile cruiser, two guided missile destroyers, and one nuclear-powered attack submarine. The mission of the non-carrier ships is to protect and defend the carrier, but many also pack a considerable amount of firepower of their own, including Tomahawk land attack cruise missiles.

Nuclear weapons, once a staple on aircraft carriers, were withdrawn from the fleet in the 1990s.

Ten of the eleven carriers are based in the United States, split between the East and West coasts. One carrier, the USS Ronald Reagan, is homeported at Yokosuka, Japan. At least three carriers are at sea at any time, with another three returning from a deployment or preparing for one. The remaining carriers are typically in a lengthy overhaul and modernization process that leaves them undeployable for two to three years.

Other countries are signaling their continued faith in the aircraft carrier concept by building their own ships. The United Kingdom recently commissioned two new carriers, Queen Elizabeth and Prince of Wales, and Brazil is experimenting with using drones from its second-hand carrier Atlantico. Japan is converting two destroyers over to a carrier configuration. France, South Korea, and Russia have all announced plans to build carriers in the near future.

The Carrier Evolves With the Times

Aircraft carriers have survived as the dominant weapon at sea for one reason: they’re almost completely unarmed. The ship is merely a floating airport, and the carrier’s real power—and relevance—stems from the air wing. As aviation changes, carriers have easily adapted to embark the latest technology, from piston to jet engines, and from unguided bombs and torpedoes to the latest laser or GPS-guided weapons.

Today the air wing continues to change to adapt to the times. A focus on China’s rapidly expanding navy is seeing carriers add the new Long Range Anti-Ship Missile, carried by the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet, and new MQ-25A Stingray aerial refueling drone. Adding new weapons merely requires ensuring carrier-based aircraft can carry them, and adding new missions requires merely developing new aircraft.

Nuclear-powered carriers, like those operated by the U.S. and France, have unique advantages, such as traveling at high speeds—a minimum advertised speed of 33 knots—for months without refueling. This allows nuclear powered carriers to quickly steam to hotspots around the world, responding faster to global crises.

U.S. Navy carriers also feature larger, more versatile air wings. Unlike Russia’s Admiral Kuznetsov and China’s Liaoning and Shandong, U.S. carriers embark E-2 Hawkeye early warning and control aircraft that can act as flying radar pickets, standing watch against a multitude of threats from surface ships to ballistic missiles. American carriers also embark up to 30 percent more strike fighters, and the only fifth generation fighter jet, the F-35C.

“The innate flexibility of a big flat deck in influencing its surroundings is unmatched.” Craig Hooper, a naval analyst and CEO of Themistocles Advisory Group, told Popular Mechanics. “Shifts in airborne capabilities and the widespread adoption of unmanned platforms may change the game a bit, but many of these platforms will still need fuel, ammo and maintenance—and that can really only be offered at sea by a flat-deck carrier.

“It may well be that carriers are something of a self-sustaining capability.” Hooper continued. “As more countries develop and deploy aircraft carriers, the best answer right now may well be to build another carrier. That said, we do need to leverage the innovation our big flat-decks offer. With unmanned aircraft prototypes emerging at a blistering pace, we need to move faster in getting them aboard.”

...But Threat Evolves Too

Thirty years after the Cold War, a new generation of weapons has evolved to threaten aircraft carriers. One such weapon type is China’s growing arsenal of anti-ship ballistic missiles, including the DF-21D and DF-26, capable of targeting a moving aircraft carrier at a range of up to 2,485 miles. This is considerably farther than the range of the strike fighters that make up a carrier’s air wing; to strike those missiles, the carrier must sail well within range of them. That’s a risky proposition considering an aircraft carrier is a national strategic asset and home to 6,000 sailors.

Russia has also developed new anti-ship weapons. The new Kinzhal hypersonic weapon, developed from the Iskander-M land-based ballistic missile, is launched from a modified MiG-31 fighter. Kinzhal has a top speed of Mach 10, which would complicate a defender’s ability to shoot it down. It is also reportedly nuclear-capable, and although U.S. carriers are designed with nuclear weapons in mind such a weapon would almost certainly be crippling, if not fatal.

There aren’t a lot of things that can sink an aircraft carrier, especially in peacetime. One that just might do the trick is cost: the latest carrier, USS Ford cost a staggering $13 billion to develop and build. And that’s just the ship itself: the cost of a new air wing of 74 aircraft is about $6.5 billion, and the cost of the escort ships another $10 billion. Thirty billion dollars is a lot just to put 44 strike fighters into the air, and is exponentially more than the cost of carriers and aircraft built during World War II, even factoring inflation.

Unlike conventionally powered ships, nuclear-powered carriers are expensive even to scrap. The USS Bonhomme Richard, gutted by a fire in 2020, was half the size of a carrier and cost $30 million to dispose of. The nuclear-powered USS Enterprise, however, might cost between $1-$1.5 billion to scrap, with most of the cost going to properly disposing of the ship’s eight Westinghouse A2W nuclear reactors.

What’s Next

Despite new dangers, the Navy still has confidence in the aircraft carrier. The service is planning to build three more flat-tops after Ford: John F. Kennedy, Enterprise, and Doris Miller. At the same time, the service is planning to introduce the MQ-25A Stingray aerial refueling drone in the late 2020s and the Next Generation Air Dominance Fighter to replace the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet starting in the 2030s. At this rate Ford-class carriers will replace the existing Nimitz-class carriers currently in the fleet, in a process that will stretch to 2050--and beyond.

Ford-class carriers are also equipped with technology that will allow the platform to grow with the times, such as electromagnetic aircraft catapults that allow for the launch of smaller, lighter, unmanned drones. Additionally, the ships are built with increased power generation capability to handle elec with increased capability to generate increased electrical power for weapons such as defensive lasers and railguns.

The Navy could take other measures to curb costs. Uncrewed fighters could join crewed fighters on the carrier flight deck, including smaller drones to fight alongside crewed fighters and eventually pilotless drones that can fight on their own. Either will be much cheaper than manned aircraft and will help reverse the trend of unaffordable naval air power. Pilotless drones, by their nature smaller than piloted drones, could lead to smaller, cheaper aircraft carriers.

Other measures could make carriers more survivable. The Navy could preemptively disrupt the “kill chain” of enemy forces, the web of sensors, communications, and weapons that would locate, target, and attack carriers at sea, foiling an attack before it could take place. It could also harden the fleet, by improving the layered defenses of missiles, guns, and lasers that protect a carrier strike group. It could even transform carriers into submarines, ships that only surface to launch and recover armed combat drones.

The Endlessly Adapting Weapon System

Aircraft carriers have always faced challenges, from kamikaze attacks to the atom bomb, only to sail through them to the other side stronger than ever before. In both cases carriers co-opted the threat by adding them to their arsenal, in the form of cruise missiles and nuclear bombs, making them deadlier than ever before. Like America itself, carriers seemingly have an endless capacity to change with the times.

Still, nothing lasts forever. Inevitably some new technology will upend the standing order and the time of the carrier, like all weapons, will come to an end. It is vital that the United States, having invested in the carrier concept more than any other country, be realistic about when the sun finally sets on the platform.

“We put a ton of money into flat-tops.” Hooper says. “We had better do everything we can to get a good return on our investment. They need to offer users an enormous amount of value both in times of war and in times of peace.”

For now, the Navy must ensure it gets maximum advantage from its eleven aircraft carriers.

🎥 Now Watch This:

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies