The True Story of Halston's Extraordinary Rise and Tragic Downfall

All it took to change Roy Halston Frowick's life was one extraordinary hat. In 1961, up-and-coming milliner Halston (who would later become known mononymously) exploded onto the national stage when Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis wore one of his designs to her husband's presidential inauguration: a powder blue pillbox hat. Life was never the same again for Halston, who became America's first superstar designer, and whose name would become synonymous with the slinky, sensual fashion of the disco era.

Halston has come back into the spotlight on the occasion of Netflix's Halston, a Ryan Murphy series tracing the pioneering designer's dizzying rise and tragic fall. Opening in Bergdorf Goodman's hat shop in 1961, the series follows Halston through formative professional experiences like the release of his breakthrough Ultrasuede shirtdress, the sensation he caused at the 1973 Battles of Versailles, and the expansion of his bespoke business into a multimillion dollar retail empire. Underscoring Halston's achievements was his hard-partying lifestyle at New York's storied Studio 54, where a combination of drugs, sex, and false friends left him increasingly volatile. Halston's troubled personal life would contribute to his eventual professional downfall, leading him to a much-maligned collaboration with JCPenney, and to a fatal business deal in which he sold off his most valuable asset: his name.

Hal Rubenstein, a founding editor of InStyle and the author of 100 Unforgettable Dresses, rubbed elbows with Halston during the Studio 54 days. Rubenstein spoke with Esquire about Halston's inimitable talent, his tragic downfall, and how he changed the face of fashion forever.

Esquire: When did you first become aware of Halston, and what were your impressions of his designs?

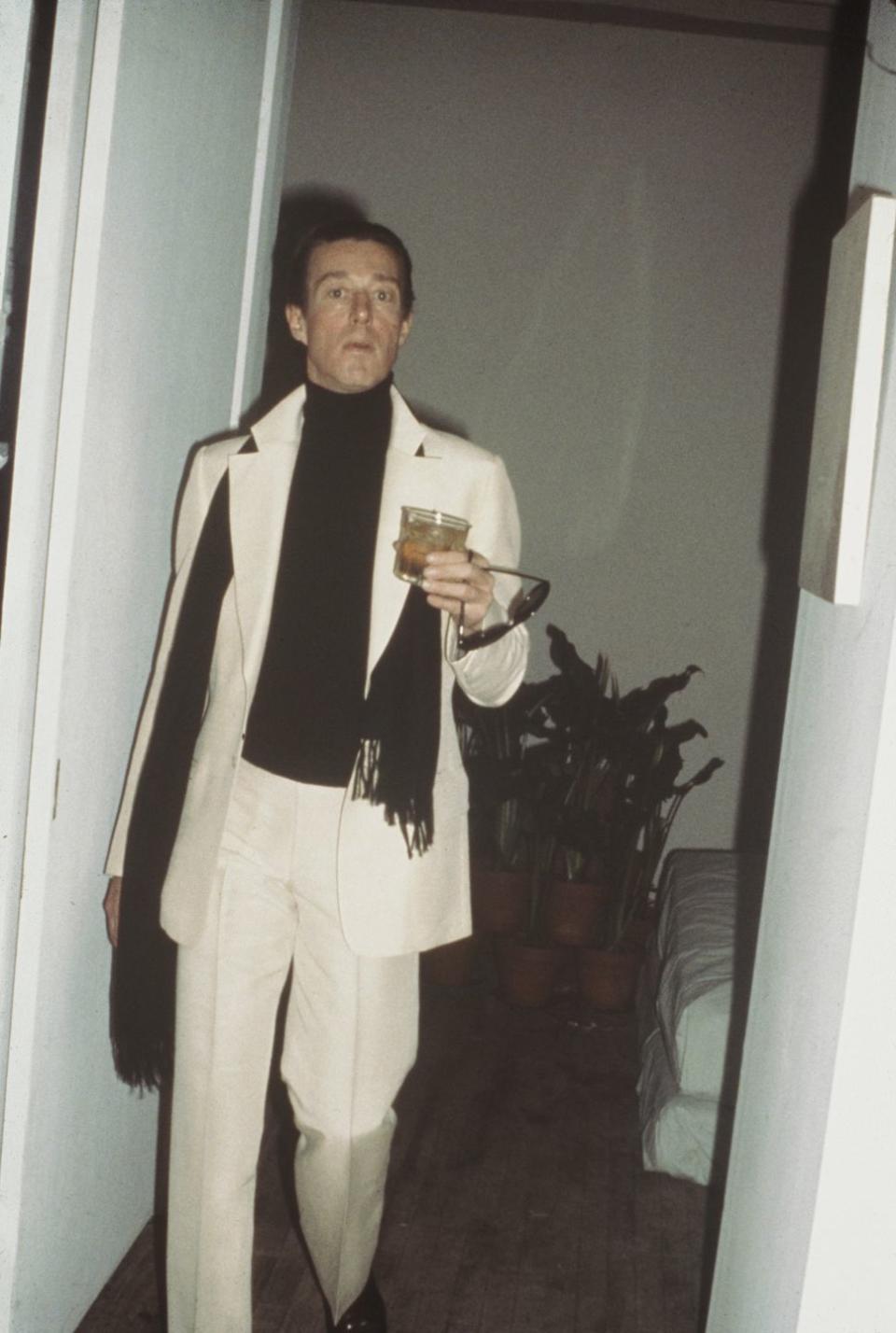

Hal Rubenstein: Halston started working in the late sixties and took off in the seventies. At that time, I was just starting out. However, I was a young gay guy, and I was out everywhere in New York. The seventies were an odd time in the sense that New York was dirty and dangerous, yet there was an incredible energy. This was right after Woodstock—all free love and sexual revolution. It was a period where New York was extremely hedonistic. Whether you were straight or gay, it didn’t matter. You went out five or six nights a week.

Halston was around at that time. Nationally, everybody became first aware of Halston at the Kennedy inauguration. I was around ten, so I certainly wasn't paying attention to who did Jackie’s pillbox hat. But the interesting thing about Halston was the clarity of design. My grandmother was a dressmaker, so I did care about clothes, and I knew about Seventh Avenue. You’ve got to place Halston in context with the other designers of the era. At the time, fashion was big, flamboyant, and stiff. It was about taffeta and heavy satin. Here came Halston with clothes that just seemed to flow. If anything, I think the clothes were deceptive. This man could cut a bolt of fabric with one slit or one seam; the dresses didn't have hooks or zippers.

Esquire: Did you ever meet Halston?

HR: There was a whole series of gay designers working in that particular period of time, but no one was openly gay. Halston never said anywhere in public that he was gay. Calvin Klein never said anywhere in public that he was gay. But what stands out about Halston, when you look at him and the entourage he traveled with, is that the entourage was a safety net. I only got to meet Halston a handful of times, both at Studio 54 and in his home, once or twice. If you were young, gay, and cute, you were summoned.

I found the group pretty boring, but they were there for insulation more than anything else, simply because designers didn’t have superstar status in the sixties and seventies. Halston was the first to stand in elevation and create an ethos where the name mattered. There were Bill Blass and Oscar de la Renta, but they worked in service of society. The whole idea back then was that you were coveting society. You ingratiated yourself with the grand society dames. Very often, designers accompanied these society ladies to parties and events, if their husbands didn't. These women wore Halston's clothes, but he never ingratiated himself with them, nor did they invite him to events. Other designers of that era became mixed with society, even though they worked in service to society. They weren't regarded as equals. Designers were workmen, and Halston didn't take to that. He decided that he was going to create his own little world, and he did. He took a page from his friend Andy Warhol, who created his own little kingdom at the Factory, which insulated him. That’s one of the reasons he became America's superstar artist of the era.

Halston said, "I'm going to create my own little circle of acolytes, friends, and assistants." He didn't mix with other designers. He wasn't friendly with them. He considered Calvin Klein and Oscar de la Renta staunch rivals. In that sense, he elevated himself above it all. Another reason why he wasn’t invited many places was the drugs. He also wasn't a patron of the arts, the way you were supposed to be during that period, where you went to the ballet and supported the opera at these big night-out charity functions. You won't see photographs of Halston at any of these things. He wasn't very culturally mature, so consequently, these events didn't interest him. He didn't spend time in the fabric of the people who were actually buying his clothes.

ESQ: What were your impressions of Halston personally?

HR: Everybody recognised his talent, but he was standoffish. At Studio, he and his entourage would position themselves on a sofa and hold court. The reality was, nobody really gave a shit. When I was in the Studio 54 documentary, I said to the director, "If you quote me saying just one thing, it would be this: the reason why Studio was there in the seventies was because being gay became very cool.” We controlled music, fashion, dance, photography, and clubs. I couldn’t understand the point of being straight. At Studio, the whole concept was that people came to watch the pretty gay boys dance. I never waited more than 27 seconds to get in.

Halston would take a group to the corner to watch the gay boys dance. If they liked you, they called you over. If they didn't like you, they were very distant. He always sectioned himself off. They were all so smashed out that they couldn't talk and couldn't dance. At his house on 63rd Street, it was the same thing. It actually was boring. There was no energy. Everybody seemed to be so pleased with themselves.

ESQ: In 1983, Halston debuted the Halston III line in JCPenney stores. It was the first "masstige" fashion line, where a mass market retailer collaborated with a high-end designer to develop a signature line. What was so revolutionary about this deal?

HR: Halston understood one thing: the democratisation of fashion. He understood that fashion had to reach more than a bunch of society ladies. Looking at it now, it’s hard to imagine why this would be a big deal, but at the time, society had a greater caste-like stratification. If you were a designer, you sold to stores like Bergdorf and Saks. You didn't sell to Macy's or JCPenney, because that wasn’t where designers worked.

But if you take it back further, I think the moment that tipped off Halston's understanding of fashion as democratic was when he created the Ultrasuede dress in 1972. He didn't invent Ultrasuede; it was actually a fabric developed by Toray Industries in 1970 for interiors and automobile upholstery. He wasn't even the first designer to use Ultrasuede. In fact, the first name for it was Ecsaine; Bill Blass and Calvin Klein used it. Blass and Klein called it Aquasuede because it was washable. But in 1972, Halston released Dress 704, a fully button-down shirtwaist dress made of Ultrasuede. Even though it had that look of being frail, you could throw it in the washing machine on spin dry. It was priced at $185, which wasn’t cheap, but wasn’t a fortune. They sold 60,000 Ultrasuede dresses during that first season alone.

It threw other designers, because he created something that was obviously revolutionary, but it was also real fashion. With most society women, half their clothes spent half their time at the dry cleaner. Here was something you could throw in a washing machine. It was cut and shaped so brilliantly that it flattered everybody. Because he was a minimalist, the clothes appealed to a greater group of people, simply because they didn't look "fancy.” The stuff looked wearable. Halston's clothes are deceptively simple, but the construction is incredibly brilliant.

ESQ: How did society react to the JCPenney deal?

HR: Nowadays, Karl Lagerfeld does a collection with H&M, or Missoni collaborates with Target, and we say, “Cool!” In the 1980s and 1990s, when infomercials started coming out, Cher did an infomercial for skincare. She was castigated. Now every night, I have to see Jennifer Aniston call up her girlfriends about Aveeno, and she’s pocketing millions. Brad Pitt sells beer in Japan. George Clooney's selling espresso, and nobody seems to have a problem with it. Back then, it was a big deal in a negative way. The idea that you went to a mass commercial retailer when you were supposed to be an ivory tower type… you’d get clobbered. The moment Halston agreed to make clothes for JCPenney, Bergdorf Goodman said, “Screw this. If you're going to sell to JCPenney, don't sell to me.” Park Avenue ladies said, “I'm not wearing clothes that suburban women can get from the same designer.” He diluted his brand—fatally so.

ESQ: Did the deal with JCPenney hasten Halston's professional downfall? Were other factors at play?

HR: When Halston sold his company to Norton Simon, it was out of a desire to expand the business, but it was also because he was running through money like crazy to finance his drug addiction. He spent thousands a year on orchids. He wasn't as professional as he should have been. A lot of the hangers-on around him sponged off of him, like Victor Hugo [Halston's lover], who had no talent whatsoever other than one appendage. They call him an illustrator—go find an illustration by Victor Hugo. You won’t find any. He claimed he did Halston's windows, but Halston's windows were terrible. The guy had zero talent. He stole from Halston as he was dying.

Look at the focus and drive of someone like Calvin Klein in creating his company. The drugs took that away from Halston. What every designer needs is a great money person. Calvin had Barry Schwartz, but Halston didn't cultivate that partner. When he did sell the company, he didn’t read the fine print and chose badly. The deal with JCPenney was actually done to get a cash infusion to prop up the company.

ESQ: You've touched on a lot of the nails in the coffin of Halston's business. Do you see any single factor as the architect of his downfall, or was it a combination of different forces?

HR: I think the selling of his name was a consequence of the drugs. The man was an addict. When someone has that level of addiction, especially during that era of cocaine and LSD and indulgence, you run through money like water. You don't think about anything but being high. It changes you. It affects your judgment. You become irrational. Your focus on your work becomes secondary to your focus on acquisition. Designers have money, but not a bottomless pit of money. The man lived high, with the luxurious home, the Olympic Towers office, and a circle of people sponging off of him. It was nothing more than somebody living beyond his means. If you're out all night, getting up late, missing appointments, and not cultivating that circle of admirers who buy your clothes, eventually they move on. These people who hung around with Halston didn't necessarily work for him or help them produce anything. It was a bunch of hangers-on sucking a man dry. Consequently, you watch a man's talent being destroyed because of his extracurricular activities. It's a sad story. The man had an extraordinary talent, but tragically, he was an addict. Like most great artists who fall prey to their neuroses, it destroyed him. It hurt his brand, hurt his name, hurt his legacy, and that's a shame. I wish he’d had more people of purpose around him.

ESQ: Halston famously said, "I want to dress all of America." How did he pave the way for more inclusivity and representation in the fashion world?

HR: At that time, there was a huge division between who did print and who did runway. There were three levels of models: women who did catalogues, women who walked runways, and women who posed for magazines. Print was the highest level. At the Battle of Versailles, Halston took three models of colour: Alva Chinn, Pat Cleveland, and Bethann Hardison. Much has been written about how the French showed up with elaborate, highfalutin, almost operatic sets. The Americans used backdrops and disco music. Some of the sets they brought over didn’t work in the space, but what they had was models. Halston and Stephen Burrows had women of colour. They told their models, “Don't walk down the runway. We want you to dance.” Alva, Bethann, and Pat went down that runway and sold those clothes. They partied. The simplicity of the designs shone through their power of presentation. The impression they made fascinated French designers like Saint Laurent and Givenchy, who became completely enamored of these women of color as models. They began incorporating models of colour into their runway stables.

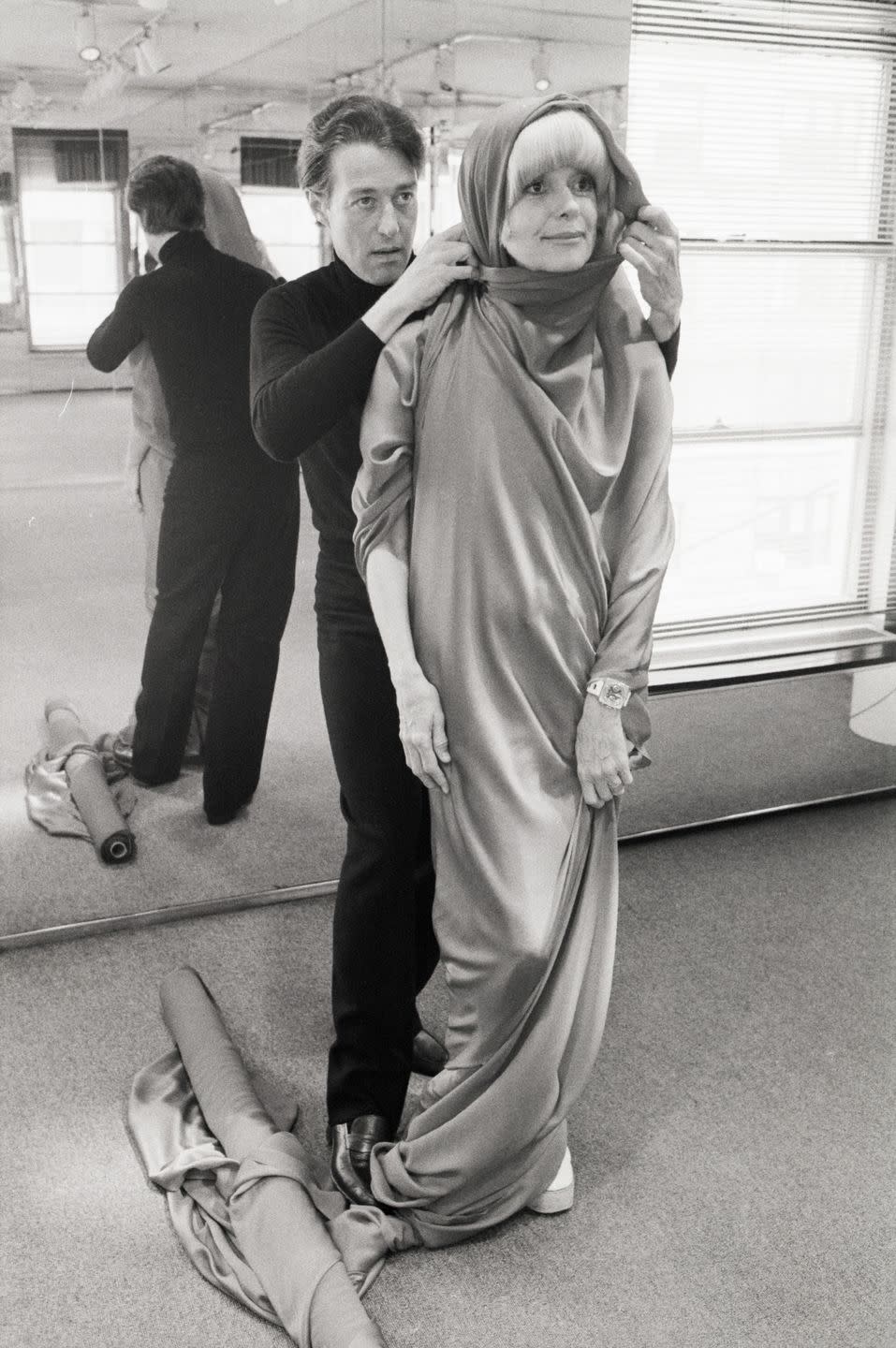

Back then, Bethann and Pat weren’t just runway models—they were fitting models. The clothes were fit directly onto their bodies. It wasn’t like, “Here's a great dress for Pat Cleveland.” Halston created that dress on Pat Cleveland. In Paris, you hired models to model your clothes. But with Halston, if Alva was wearing a dress, Halston did the dress for Alva. If Bethann was wearing a dress, the dress was made for Bethann. The impact was extraordinary, and he understood the eroticism and sexuality of it. Halston’s clothes were ridiculously sexy without being vulgar. The slit was in the leg; the neckline drop was in the back. His clothes were so sinuous. He worked in softer fabrics, like cashmere and crepe de chine and silk voile, so the clothes just floated on a woman’s body.

He was a great designer, and it's a shame he didn't have the discipline to match his talent. He was jealous of Calvin Klein, who ultimately took over his mantle, because Klein shared that ability to create clothes that looked modern and fresh, with a classic, movie-based sexuality to them. Halston lost his way, but he got there first. His dresses didn’t even have zippers. You just stepped into them. It was like wearing an incredible bathrobe that was glued onto your body. He didn't waste time on embroidery. If he did sequins, it was a sheet of head-to-toe sequins. His clothes were not about ornamentation or intricate pattern-making. He understood the sensuality of fabric against a woman's body, which was incredibly revolutionary. When you look at his contemporaries, their dresses were statements. The dresses hung on a rack and were appealing on their own. Halston's clothes hanging on a rack didn’t necessarily look all that appealing. They looked shapeless until you put them on. But it wasn't just about how it looked; it was also about how the clothes felt.

ESQ: There's a great line of dialogue in the show where a character says that Halston's dresses “wrapped a woman in a feeling.”

HR: That’s absolutely perfect. The idea of understanding or, to be honest, getting off on what it feels like to have cashmere rubbed against your body as you walk or dance. It was a great feeling of self-love. He encouraged a woman to get off on herself. That really was his mastery. He created clothes in such a way that a woman got to celebrate her own shape, but she also got to feel more powerful. The look is not just about, “I picked a great dress,” but it was about, “Look at what I look like in this dress. Look at what I feel like in this dress. What I feel like in this dress is amazing.”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies