Today's Black QBs might not know Marlin Briscoe, but they owe late pioneer a huge debt | Opinion

Young Warren Moon suddenly had a new hero.

The 12-year-old Los Angeles native loved football, and he loved playing quarterback for his Pop Warner team. But Moon never saw anyone who looked like him on the pro ranks. He did root for Roman Gabriel, the Los Angeles Rams standout and trailblazing Filipino-American.

But then, Moon discovered Marlin Briscoe – a Black man who, after being forced to convert from college quarterback to NFL cornerback, got his shot at his natural position with the Denver Broncos when the team's veteran passers were sidelined with injury.

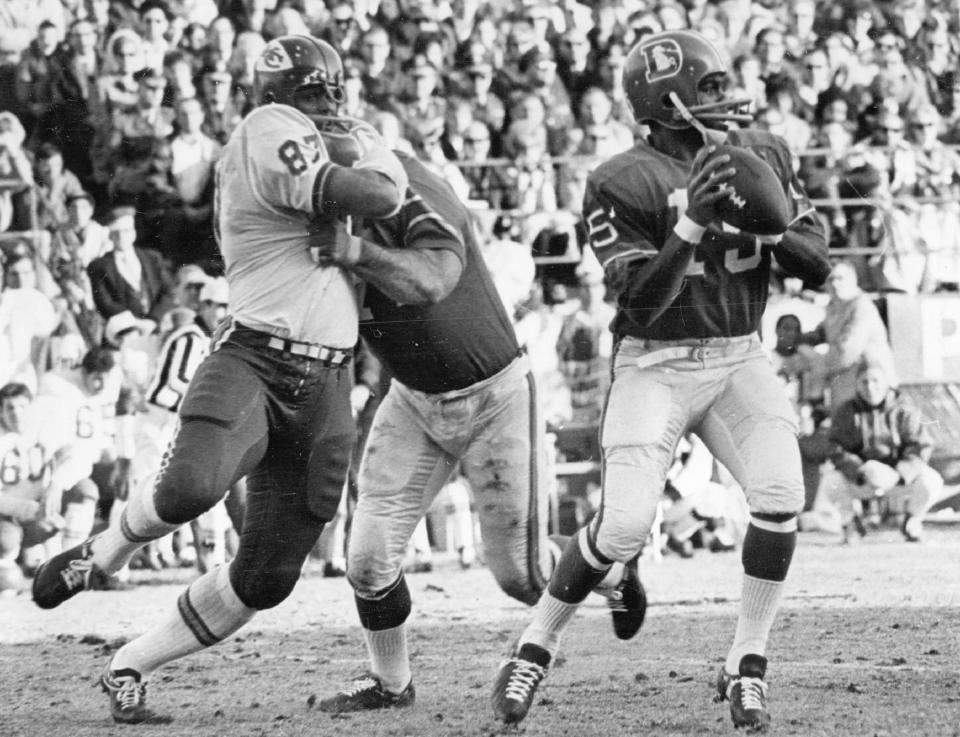

“Marlin the Magician,” as Briscoe was dubbed, parlayed a fourth-quarter relief effort in 1968 into a five-game stint as the starting quarterback to close out his rookie season.

Briscoe, who became the first Black starting quarterback in pro football’s modern era, didn’t just start. He dazzled.

Using his supreme athleticism and quick-twitch reflexes to elude defenders and his strong arm and keen instincts as a passer, Briscoe set a Broncos rookie passing record of 14 touchdowns.

“Marlin was the first guy that I saw that let me know I could keep pursuing this,” Moon told USA TODAY Sports this week while sharing his recollections of Briscoe, who on Monday died of pneumonia at 76.

“I had started playing quarterback at 10 and I always wondered what position I could play if I wasn’t able to keep playing it,” Moon continued. “But I was destined to be a quarterback and couldn’t turn my back on it, and Marlin was the inspiration. To see a Black man doing it, it really gave me a boost that helped me take off.”

Moon eventually orchestrated a renowned 22-year career as a quarterback, earning inductions into both the Canadian and Pro Football Halls of Fame. He largely credits Briscoe for fueling his success, even though his idol wasn’t nearly as fortunate.

Briscoe’s name and plight might not hold a place of prominence in the minds of today’s Black quarterbacks and fans. But he should rank high on their list of heroes.

Briscoe’s NFL career embodied one of the ugliest chapters in NFL history while also providing a glimpse into a future where supremely talented quarterbacks of color, when finally given the opportunity, dominate at an elite level.

“They should look at Marlin as a trailblazer,” Moon said. “He’s a guy that blazed a trail for guys like myself, Randall Cunningham, Vince Evans and all the guys that came after us. He was a quarterback like those of today. He could throw but he could move. He was called ‘Marlin the Magician’ because of that.

"During that time, everyone was looking for the cookie-cutter, 6-3 to 6-5 white quarterback who could stand in the pocket and throw the ball. That wasn’t Marlin, but that’s the way the game has evolved. If people want to know where the game was headed, they can look at Marlin Briscoe.”

Briscoe’s numbers spoke for themselves – and still do. His 14 passing touchdowns remain a Broncos rookie record 54 years later.

He had what it took to play quarterback at the highest level. But others rejected, disrespected or hated him for his skin color.

After that five-game stint with Denver, Briscoe never again played his beloved position again. He didn’t even get to suit up for the Broncos again. The following offseason, he learned that Denver coaches and quarterbacks had been holding meetings without telling him, and the Broncos soon traded him to Buffalo, where the Bills required Briscoe to transition to wide receiver.

“When Marlin came to Buffalo, he was bitter, and I was bitter for him,” former teammate and roommate James “Shack” Harris told USA TODAY Sports. “He was bitter because he had played well and they didn’t give him a chance. I felt his pain. … I was bitter for him and all the guys that were denied a chance to play.”

That 1969 season, Harris was another Black quarterback trying to make it in the NFL. Buffalo drafted him in the eighth round out of Grambling State but buried him on a depth chart topped by veterans Jack Kemp and Tom Flores.

Harris leaned heavily on Briscoe, who despite focusing on his fight for a roster spot as a wide receiver coached up Harris on the nuances of professional quarterbacking.

“We had to call our own plays in those days, and Jack Kemp and Tom Flores were there, so we were moving at the pace of veterans, and it was hard,” Harris said. “I understood football but not at that pace. But Marlin had been in Denver. Being able to talk to him in the evenings about the whole thing, it really helped me. We talked about play-calling, any action, what he had been through, what I was going through, how he felt coming in and all of that. He was a big help to me, just having someone to come back to.

“And practicing each day, we had seven-deep, so I wasn’t getting a lot of practice, and he was a big help to me. And he was coming in as a receiver and he wasn’t getting a lot of practice,” Harris continued. “We both realized, him as an undersized guy switching positions, he had a slim chance of making the team. And me, a Black quarterback with no experience in the league, we understood I had little chance of making the team. Back then, they were cutting players every day – 150, 125 guys, just cut you there. Marlin and I would see each other and say, ‘Well, we made it another day.’”

Briscoe would ask Harris to throw to him for 30 to 40 minutes after each practice, and eventually the work paid off. Both made the regular-season roster, and in 1970, Briscoe morphed into a Pro Bowl wideout.

Briscoe and Harris’ football journeys took them away from Buffalo. Briscoe wound up in Miami, playing a role in helping the Dolphins win two Super Bowls and earn the distinction of being the only team in NFL history to go undefeated for an entire campaign. Harris wound up in L.A., where he garnered 1974 Pro Bowl MVP honors.

But the two remained close. Upon retirement, Briscoe moved two houses down from Harris in Los Angeles.

Despite Briscoe's championship accomplishments as a wide receiver, the racial mistreatment always stung.

“I know the hard times he went through because he wasn’t allowed to play quarterback,” Moon said. “He had a hard time with drugs and alcohol at one point in his life. He overcame that and was very involved with the Boys & Girls Club much of his life after his playing days were over. That period of his life really messed with him because he knew he had the ability. He had played it at a high level all his life and in college, and then it’s taken away from him, and he really struggled.”

Briscoe lived vicariously through Harris, Moon, Doug Williams and the Black quarterbacks who came after him. In 1988, while incarcerated for drug possession, he was moved to tears while watching Williams become the first Black quarterback to win a Super Bowl.

Years later, when meeting Williams for the first time, he made a point of telling the younger quarterback about the impact his triumph had on him.

Williams, meanwhile, felt a deep sense of gratitude to Briscoe.

“You’re talking about a pioneer. Marlin was a pioneer,” Williams told USA TODAY Sports. “When you look at it, his journey was way worse than mine. He was the first guy modern-day to play the position and evidently, he played it pretty good. But it was during the time where it just wasn’t happening for Black quarterbacks.

"When I think about Marlin, I think about the opportunities I had to play this game, whether we want to accept it or not, Marlin had a handprint on the whole situation to give me that opportunity to play. ... I was given the best opportunities of any black quarterback. Shack was a starter, but as far as coming in with an open mind of ‘you are a starter’ I was the first one to do that and owe that all to Marlin.”

Briscoe always found it important to support young Black quarterbacks because he understood the challenges of playing such a demanding position while also dealing with racial persecution. In the early 2000s, Briscoe, Williams, Harris, Moon, Cunningham and Evans formed a fraternity of Black quarterbacks called “The Field Generals,” with the goal of hosting camps for young Black aspiring quarterbacks and mentoring college and pro passers of color.

Now, 54 years after NFL teams forced Briscoe out of his natural position, some of the game’s most dynamic quarterbacks are Black. Some still find themselves subjected to racially charged criticisms or attacks. However, as Williams said, Briscoe bore a far heavier and more painful burden. And for that, Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson, Russell Wilson, Kyler Murray, Deshaun Watson, Jameis Winston, Jalen Hurts, Justin Fields, Trey Lance and their brethren should count themselves blessed.

Some of them may not have known much about Briscoe prior to this week, and some of them still may not. However, Briscoe deserves their admiration and gratitude, because without trailblazers like him, their opportunities could look very different.

Follow USA TODAY Sports' Mike Jones on Twitter @ByMikeJones.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Why today's Black QBs owe late pioneer Marlin Briscoe a huge debt

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies