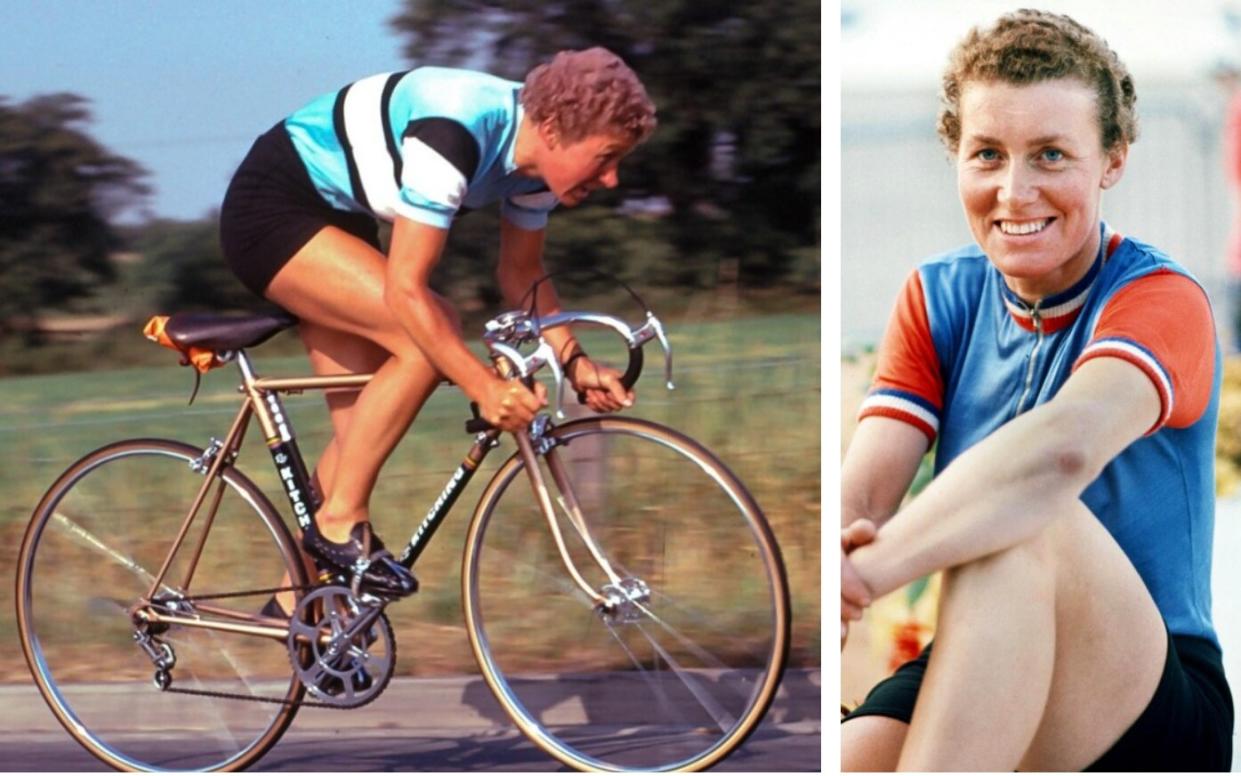

Think Serena Williams beating Roger Federer - Beryl Burton was that good

Beryl Burton woke shortly before 4.30am on the morning of Sunday, Sept 17, 1967. She liked to be up for a few hours before racing and, after a simple breakfast, had a last check of her kit: bike, cycling shoes, water bottles, flasks of tea and the small parcels of food that would be passed by her husband, Charlie, every 15 miles.

The family, including 11-year-old daughter Denise, squeezed into their Cortina car and set off on the short journey towards the Yorkshire market town of Wetherby. At 7.11am, Beryl would begin an attempt at the record for the longest distance cycled in 12 hours. Two weeks earlier, the 30-year-old had won her seventh world title, demolishing a field that included full-time state-sponsored riders from the Soviet Union and East Germany. Today, Beryl would complete a three-mile warm-up before gently pedalling up behind a queue of the last men’s riders setting off at one-minute intervals for the individual time trial.

“Thirty seconds,” said the timekeeper, Arnold Elsegood, before she was to start the women’s race. Beryl nodded. And then the words that send a surge of adrenalin through any cyclist: “Five, four, three, two, one ... Go!” Beryl muttered a “thank you”, stood up on the pedals and pressed down. “Do your best, lass – make it crack,” were Charlie’s last words as his wife disappeared into the distance for a sporting achievement that would shatter preconceptions of a woman’s capabilities in endurance sport.

As the top seed, Mike McNamara had been last of the 99 male competitors to start. There was then a two-minute gap to Beryl and what was ostensibly a separate women’s race – albeit with just four riders taking part. McNamara went through the first 100 miles in 4hr 14min 55sec, powering along at an average speed of almost 24mph. Beryl was only 58 seconds slower but, as she would later explain, had been “riding easily” at the start.

“Time passed pleasantly for the first few hours,” she said. “I felt good, the wheels hummed, and so did I now and again.” Beryl, who loved opera music, duly covered the next 100 miles in a remarkably even-paced 4-17-44 to move 18 seconds ahead of McNamara. The peculiarities of interval starts, however, meant she was physically still behind on the road and unaware that she was now leading the men’s and women’s races.

Club riders and spectators began to gather in unusually large numbers around the 15.87-mile finishing circuit near Borough-bridge as word spread locally that something special was happening. “It was mayhem,” George Baxter, a marshal on the course’s main hill, said. “No cars could get through. Only people and bikes.”

After completing the first finishing circuit, Beryl had moved 42 seconds ahead of McNamara in terms of timing, and so physically was only 78 seconds behind on the road. Charlie began shouting times at Beryl as she passed, increasingly excited by what might be. His wife still felt physically strong but had developed stomach cramps, perhaps a result of the fresh steak that her husband had been passing up after cooking them on a roadside Primus stove. A Rennie washed down with a mouthful of brandy soon solved the problem and, after 235 miles and more than 10 hours of continuous cycling, McNamara finally came into view.

They were completely alone. No witnesses were present for this unique moment in sporting history. Beryl later recounted her thoughts in her 1986 autobiography Personal Best: “I came to within a few yards of him and then I froze, the urge in my legs to go faster vanished. Goose pimples broke out all over me. I could hardly accept that after all those hours and miles I had finally caught up with one of the country’s great riders who, himself, was pulling out a record ride. ‘Poor Mac, it doesn’t seem fair,’ I thought. I drew alongside … then came the moment which has now passed into cycling legend.”

Speak to almost anyone – male or female – who raced in Britain during the 1960s or 1970s and they will invariably tell you about the experience of being caught by Beryl Burton. She saw other cyclists the way a swallow might view a fly, gobbling up thousands in her career. Most just ignore the person they are passing, but it is considered good etiquette to offer a word or two of encouragement. Beryl always said something but, in her blunt Yorkshire twang, was just as likely to say something cutting. “C’mon lad, you’re not trying!” was one favoured remark. So what would Beryl say to McNamara, the leading men’s time triallist of the time, who was producing the best performance of his life? “Mac raised his head slightly and we looked at each other side by side,” she said. “I was carrying a bag of Liquorice Allsorts in the pocket of my jersey and on impulse I groped into my sweetie bag and pulled one out. It was one of those Swiss roll-shaped ones. White, with a black coating. ‘Liquorice Allsort, Mac?’ I shouted. He gave a wan smile. ‘Ta, love,’ he said, popping the sweet into his mouth. I put my head down and drew away.

“There I was, first on the road, 99 men behind me. Mac was doing a sensational ride but his glory, richly deserved, was going to be overshadowed by a woman.”

Marshals were positioned around the finishing circuit and, with his 12 hours up at exactly 7.09pm, McNamara was signalled to stop. Beryl had until 7.11pm and, having pedalled a further three-quarters of a mile up the road, flopped down on a large patch of grass by the A59. Her final distance read 277.25 miles, amounting to an average speed of 23.1mph through 720 continuous minutes of effort.

She had ridden almost 40 miles further than the next-best woman had ever managed and almost six miles more than the previous men’s record, which had itself been broken two minutes earlier by McNamara. Burton’s 12-hour women’s record would stand for half a century before finally being broken by Alice Lethbridge in 2017, several decades after cycling’s aerodynamic revolution had transformed time-trialling speeds. Wind-tunnel tests have subsequently estimated that Beryl’s 277.25 miles would equate to 305.25 miles on modern technology – over 15 miles more than the current women’s record, and still good enough to win two of the past three British men’s 12-hour championships.

“As far as I know, in all of sport, it has never happened that a woman has broken a men’s record,” Phil Liggett, the cycling commentator, said. Another celebrated male rider she passed that day was Keith Lambert, a future triple British professional men’s road race champion. Beryl had started 18 minutes behind Lambert before reeling him in. “I think she said something like, ‘C’mon lad, what are you doing?’,” Lambert said, shaking his head.

“What a day. Goodness me. Unbelievable. She was as hard as nails. A phenomenon.”

Beryl would see McNamara at hundreds of events in the years that followed, but they never once discussed a duel in the vein of Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes”. Seven years later, that televised tennis contest would be watched by 90 million people, tuning in to see a woman beat a man. How things might have been different for cycling, had those same sports fans been able to see Beryl and McNamara – two athletes at the peak of their powers – battle it out for supremacy. “People regularly still ask me how good Beryl was, and the best way I can put it is this,” McNamara’s brother, John, said. “Just imagine that Serena Williams played Roger Federer at Wimble-don. And imagine that she beat him. That’s how good Beryl was.”

‘We put in same hours and make same sacrifices’

Burton’s prize for her 12-hour ride in 1967 that surpassed both the women’s and men’s records? The precise sum of £1/10 shillings. And yet for Mike McNamara, the fastest in an entire field of 99 men whom she also caught and beat? Almost three times as much at £4.

The discrepancy will come as little shock to anyone who rode in an era when prizes for women cyclists were as likely to be pouches of washing powder or hair-curling tongs as money and trophies. Rather more surprising, however, is what happened when one of sport’s greatest records was finally beaten.

Alice Lethbridge, a biology teacher from Surrey, achieved that feat some 50 years later in 2017, but her £40 prize was only the same as the third-placed man that day.

“Prize allocations in time trials are still completely down to the discretion of the organiser,” Lethbridge explains. “Some are brilliant, but a lot of organisers will say, ‘I am not giving the winning woman the same as the leading man because she is racing against fewer people’.

“Being told that our performances are not equal to men’s is a common theme when we raise this. But when you have ridden a time that was really high on the all-time list and you are getting less than the leading man who is nowhere near top of the men’s list, you do think, ‘What more can I do to be respected as a cyclist in the same way as the male competitors?’ ”

Cycling was more than 50 years behind swimming and athletics in allowing women into the Olympics in 1984 at Los Angeles, and the very fact that the Tour de France Femmes – a women’s race finally to compare to the men’s Tour de France – is being relaunched this year tells its own story.

Previous incarnations were staged only intermittently between 1984 and 2009.

Vast disparities also remain inside the women’s professional peloton and, even for the history-making winner at the top of La Super Planche des Belles at the end of the eight-stage race on July 31, the €50,000 (£43,000) first prize will be a mere tenth of what is on offer to the men.

Such discrepancies were highlighted in a parliamentary debate earlier this year following the launch of The Telegraph’s “Close the gap” campaign for fair prize money in sport. Backers of the campaign include the cyclists Lizzie Deignan and Laura Kenny.

“As female athletes, we put in the same number of hours and make the same sacrifices, yet our rewards are completely different,” said Kenny, Team GB’s most successful female Olympian. “What message does this send?”

Deignan was awarded a first prize of just £1,313 compared to more than £25,000 for the men when she won the first women’s Paris-Roubaix last year.

There is at least now a minimum wage for leading women’s professional cycling teams, but you do not have to scratch far beneath the surface to hear multiple stories of unpaid “professional” riders also working full-time outside the sport. Lethbridge, who is 37, combines her job as a teacher with representing Great Britain in the UCI’s Esports World Championships on Zwift and riding women’s WorldTour races for the AWOL O’Shea team.

Training is simply crammed in before school at 5am and between marking at weekends.

“For girls, it often has to be a hobby rather than a profession,” she says, even if being the person who broke Burton’s most famous record is the sort of accolade that money cannot buy.

“It was a spine-tingling moment – and even now, five years later, it still doesn’t feel real,” she says.

Another vocal champion for women’s cycling is the Eurosport presenter Orla Chennaoui.

“A survey by The Cyclists’ Alliance last year showed that there has been a growing wage disparity gap between the women’s world teams and the continental teams,” Chennaoui said.

“We have seen massive progress but, when you look at the continental teams, the number of riders not paid a salary had increased to 34 per cent in 2021.”

This reality makes prize-money critical on a practical as well as symbolic level but, having guest-edited the record-selling Rouleur magazine that exclusively featured women’s cycling, Chennaoui is certain that the interest is there.

“Women’s racing tends to be more dynamic and less formulaic,” she says. “It is all changing but disparities remain and you don’t want to be the sport that is left behind. Why be dragged into 2022?”

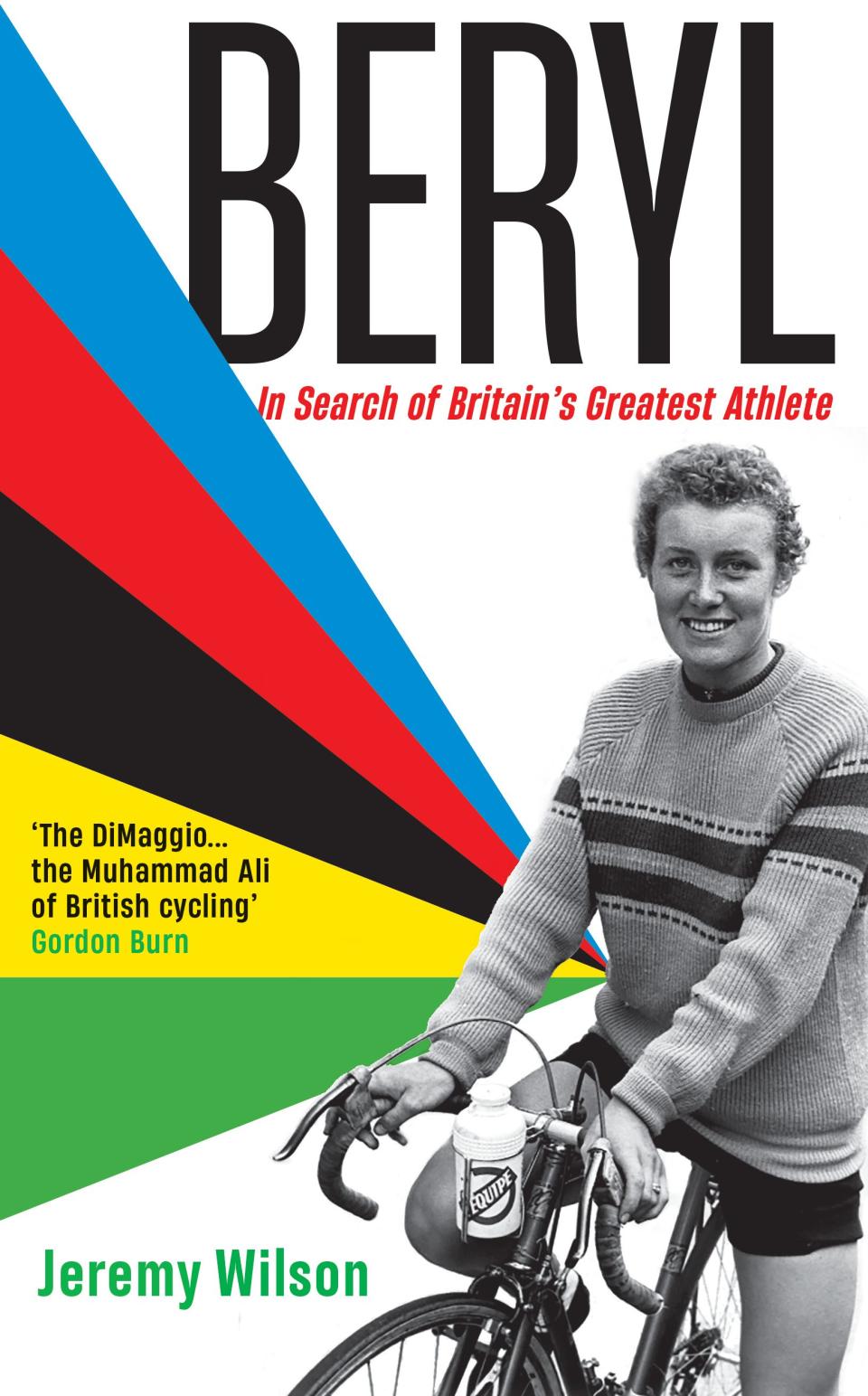

Adapted from Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete, by Jeremy Wilson (Pursuit/Profile £20), which will be out on July 7 and is available on pre-order.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies