The tawdry truth behind Fleetwood Mac’s Rumours, the greatest break-up album ever made

When Christine McVie died on Wednesday aged 79, her Fleetwood Mac bandmates described has as “one-of-a-kind, special and talented beyond measure”. She was, they said, “the best friend anyone could have in their life”.

McVie was always the grounded and sensible member of the band. It was McVie who slept on amps in the back of the tour bus in the early days. And it was McVie who greeted the arrival into Fleetwood Mac of second female singer Stevie Nicks in 1975 not with resentment but something altogether more cheery, describing Nicks as “a bright, very humorous, very direct, tough little thing.”

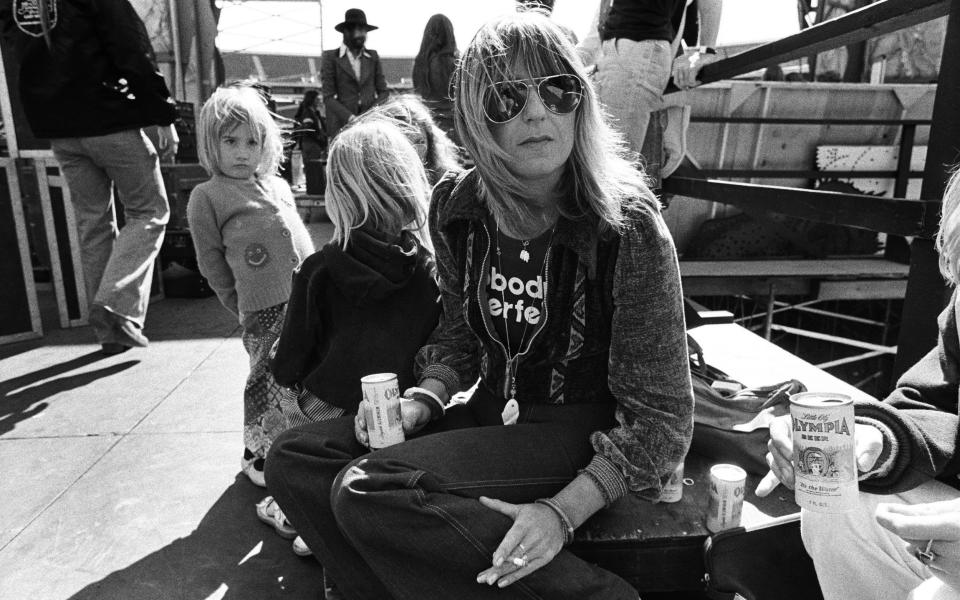

Level-headed, yes. But everything is relative. Not even the most level-headed individual would have been able to withstand the total dysfunction that was corroding the Fleetwood Mac camp in the mid-1970s when they started to record their masterpiece Rumours. Not only were the personal lives of all five members in turmoil, but this turmoil largely involved each other.

“Drama. Dra-ma,” was how Christine McVie described the process of recording Rumours to Rolling Stone shortly before its February 1977 release. That was something of an understatement.

The group began recording Rumours as a follow-up to their 1975 self-titled album, which had topped the charts in the US. Expectations were high. But have a look at the romantic scorecard going into the studio. Drummer Mick Fleetwood and his wife Jenny Boyd, sister of model Pattie Boyd, had separated after he discovered she’d been having an affair with his friend and touring band member Bob Weston. Christine and her husband John McVie (on bass) were divorcing after eight years of marriage, and relatively new members Lindsey Buckingham and Nicks – who’d joined as a romantic as well as a musical couple – had experienced a brutal collapse in their relationship. It was a mess.

On top of this, cocaine was rife. A black velvet bag of the drug was a constant presence on the mixing desk. “It was music through chemistry,” is how Buckingham has described it. At one session, engineer Ken Caillat brought in a bag full of talcum powder and emptied it all over the floor. The hoax was revealed, but not before it had raised the ire of Fleetwood and John McVie.

“Everyone was pretty weirded out,” Christine McVie told Rolling Stone. “But somehow Mick [Fleetwood] was there, the figurehead. ‘We must carry on, let’s be mature about this, sort it out.’” And bruised, bitter, cagey and at each others’ throats as they were, the band managed to produce the greatest break-up album of all time, capturing perfectly the attendant love, hate, passion and resentment.

Not that it was easy. Most of Rumours was recorded over a year at the Record Plant studio in Sausalito, near San Francisco. Fleetwood has said that “the emotional rollercoaster was in full motion” when they started. “My best friend was having an affair with my wife and it was all weird and twisted,” the drummer told Uncut in 2013. To get through it, Christine McVie – ever the pragmatist – said that she and Nicks were bound by a mutual “sense of humour through all the pain”. Plans for them all to live under one roof at the studio lasted for just one night, with the female members resenting the frat-house atmosphere caused by the presence of a number of hangers-on (Nicks described it as a “riot house”).

McVie had been through emotional turmoil. In the run-up to her separation with John, she said she’d been seeing “more Hyde than Jekyll” in his behaviour due to his drinking. “I had to [break up with him] for my sanity. It was either that or me ending up in a lunatic asylum,” she told Rolling Stone. By the time of the Rumours recording, the pair weren’t talking to each other. “We literally didn’t talk, other than to say, ‘What key is this song in?’” McVie has said. “We were as cold as ice to each other because John found it easier that way.” To make matters worse (for John, as it happens), McVie had embarked on an affair with the band’s lighting director Curry Grant. “Wherever John was, he couldn’t be. There were some very delicate moments,” she said.

Psychodramas were playing out everywhere. But the warring Nicks and Buckingham were too proud to walk away from the band. And Buckingham and John McVie locked horns over the creative process. At one point, the bass player threw a glass of vodka in Buckingham’s face. Still, according to Christine McVie, the end product transcended “everyone’s misery and depression”. Rumours works as an album because the songwriting was split between her, Buckingham and Nicks. It therefore told of the romantic chaos from competing points of view. All opinions were subjective, like entries in secret diaries set to music. Everything was bundled up in conjecture, clouded by rumours.

There could have been little doubt who Nicks was referring to in Dreams when she sang, “Now here you go again/ You say you want your freedom.” Nor was there any ambiguity in Buckingham’s Go Your Own Way when he replied, “Loving you/ Isn’t the right thing to do.” And then there was Christine McVie’s input.

Her song You Make Loving Fun was inspired by her affair with Grant. To avoid a row, she apparently told John that the song was about her dog. Don’t Stop, meanwhile, is about looking to the future. “All I want is to see you smile/ If it takes just a little while… Don’t stop thinking about tomorrow,” McVie sang. But the album’s highlight for many is McVie’s Songbird, a desperately sad yet uplifting piano ballad in which she says she loves an unknown person “like never before”. McVie once said that rather than relate to anyone in particular, Songbird “relates to everybody”. It is three minutes and 20 seconds of pure catharsis and arguably the emotional heart of the album.

Rumours took off, but not before Melody Maker slated it as “very thin musically, full of stereotypes, easily assimilated formulae and bland techniques” (the review introduced the term “middle of the road” to music journalism). It sold ten million copies within a month of its release and over 40 million copies to date. Dreams became Fleetwood Mac’s only number one single in the US (their only UK number one was Albatross in 1968). That song still resonates: it became a TikTok phenomenon in 2020 after a skateboarder posted a video that was viewed 70 million times.

After Rumours’ release, the drama continued. Nicks coupled up with Fleetwood. And Christine McVie embarked on an intense three-year relationship with the Beach Boys’ wild child Dennis Wilson.

But although she was heavily involved in the Rumours drama, McVie also played an essential role in keeping the group together over that period. In 2020 Mick Fleetwood said that McVie was “the least prima donna type of person you could ever hope to meet”. It has always been so. The band famously sang on Rumours that no-one would “ever break the chain”. And Christine McVie was the Mac’s ever-reliable link.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies