I Was Taught Not To Tell Anyone I Was Jewish. Here's What Happened When I Finally Did.

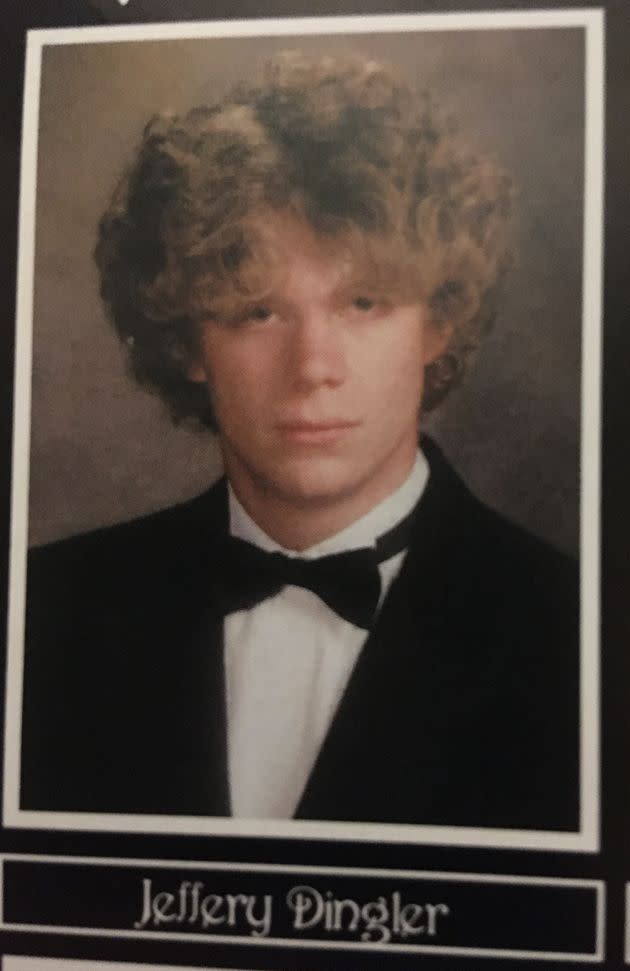

The author, pictured in his senior photo, was called "the Jew” or just “Jew" by some classmates in school.

The recent antics of the unlikely trifecta of former President Trump, world’s richest man Elon Musk and superstar rapper Ye (formerly Kanye West) have proven once again that being Jewish in America is complicated.

This isn’t news to us. Antisemitic incidents in the U.S., which have been rising for years, hit an all-time high in 2021. Just under a year ago, on the morning of Jan. 15, a gunman held four people hostage in a small-town Texan synagogue. I wasn’t shocked. I wasn’t even surprised. When you’re Jewish, you come to expect this.

Home during winter break from grad school, I walked up to my mother’s room to share the news. When I told her what was happening, her response echoed a deep-seated family belief: “This is why we don’t go to synagogue. This is what your grandfather feared.”

I didn’t grow up in New York or Boston or Los Angeles, where there are sizable Jewish populations. My siblings and I were raised in a small conservative town in rural Alabama. When I say rural, I mean we were raised across the street from 40 acres of cow pasture. Out here in the boonies, birdsong is just as common as hearing people target practice in the woods. I had a neighbor whose son would ride a four-wheeler around with a big Rebel Flag strapped to the back of it, the crooked starry cross flapping and mud-smeared. In addition to its glorification of the painful legacy of slavery and racism, closeted Nazis and fascists frequently use the flag as something of a substitute swastika.

Growing up, we were the only Jewish family in the community. Although only a half-hour north of Birmingham, where there are three synagogues, we grew up isolated from the small Hebrew community there because my parents worked so much to provide for my siblings and me.

My mom turned on her TV, and I sat on her bed as the information trickled in about the hostage situation. The temple, called Congregation Beth Israel, belonged to the Dallas-Fort Worth suburb of Colleyville, a city of fewer than 30,000. One of the hostages was the synagogue’s rabbi.

I wanted to ask my mom if she thought this would become a new Tree of Life massacre, which left 11 Jews dead in 2018. That was Pittsburgh, a city with an old Jewish presence; a supposedly safe place for us. But I kept silent.

Being Jewish in the United States is not black and white. It’s closer to gray, which was my grandfather’s Americanized surname. He was Czech, a Holocaust survivor, refugee and immigrant who died in 1992 from what my family believes to be depression and a shattered heart.

He could’ve chosen a number of names that would’ve better reflected what he was given at birth: Goldberger. My grandfather could’ve been Eugene Gold, a perfect name for what he became in the United States: a helpless gambler and door-to-door salesman.

Instead, he chose the color gray exactly because it sounded generic, so it ― and he ― would blend, like a puff of smoke fading into blue air. Except my grandfather misspelled it as “Graye,” perhaps as a quiet rebellion to signify he was different, foreign.

Eugene never talked about the before-life. He was just a teenager when Hitler rose to power. His story, what happened during the war, went with him when he passed when I was 5. There are a few photos of him in our family album, but I have no memories of him.

About a half-hour intowatching the hostage story, I heard my mother talk over the news anchors: “What did Grandpa Graye always say?”

I already knew the litany. “Don’t go to synagogue. Don’t put your names on any lists. Don’t tell anyone you’re Jewish.” She shook her head and puffed on her vaporizer.

I asked Mom: “You don’t feel like you’re hidden, like you’ve lived a closeted life?” My mother was born in Detroit and grew up in Michigan, but Grandpa Graye taught her the same things she taught me: Don’t tell anyone that you’re Jewish. Don’t let them know. Don’t even wear a Star of David around your neck.

My mother shook her head. “I don’t view it that way because you’ve got your religious Jews, and your cultural Jews, and Jews who are just... Jews.”

According to Judaism, if your mother’s Jewish then you’re Jewish no matter what. Thisapplies to me even though my late father came from poor country people in Alabama who had no religion. It means I’m Jewish although my family and I almost never went to synagogue and only occasionally celebrated Chanukah and the high holidays.

As the news networks stalled on the hostage situation in Colleyville, Iwandered back to my room. I tried to work on my grad school thesis ― a novel on migrant prison camps on U.S. soil, about the wicked detention-deportation machinery of modern-day America ― but I couldn’t concentrate.

I thought back to when I first heard about the Tree of Life killing, and how much weight and suffering a relatively small number like 11 can carry. Multiply that number times one million and you have an idea of the weight of misery created by the Holocaust.

When I started coming out of the Jewish “closet” in middle school, I was shocked by some of the ignorance and animosity I encountered. In class, I was frequently called “the Jew” or just “Jew.” Some classmates thought this was funny or endearing. I was condemned to hell on a regular basis by people who claimed they loved me. When I was sent to the vice principal’s office for acting out over this, his first suggestion was that I shouldn’t tell anyone I was Jewish.

Being gray in America is nothing like being Black or Brown. What I’ve experienced over a lifetime is a small drop compared to the deluge that is drowning people of color.

But it was different for my grandfather and anybody who grew up Jewish in Europe before the end of WWII. Jews endured centuries of race massacres or pogroms.Even today in the United States, Jews are consistently the most targeted religious group, making up nearly 60 percent of all religiously motivated hate crimes while comprising less than two percent of the population. And, as Ye and NBA star Kyrie Irvine and so much of Elon Musk’s more hate-filled Twitter recently proved, that thinking doesn’t belong only to the folks in white hoods.

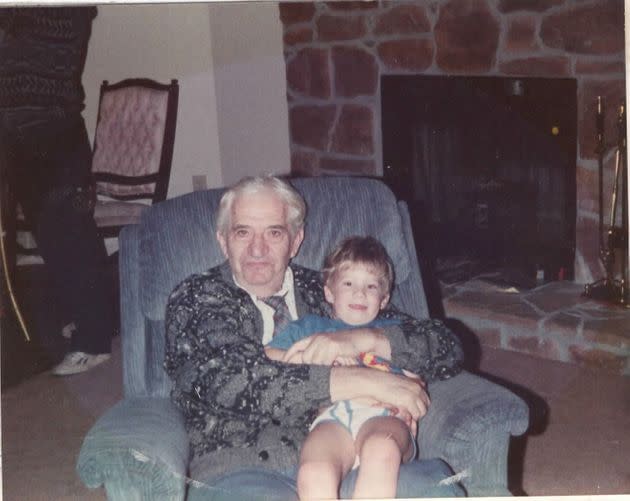

Grandpa Gene, pictured with the author's brother, chose the last name Graye when he came to the U.S.

Last January, when I reemerged from my room, many hours had passed. My mom had migrated to the downstairs living room to watch the evening news. She was only half-paying attention to the anchors as she picked at a plate of cold food.

“They all got out,” she said.

“Who got out?”

“The people trapped in the temple. They’re safe.”

“What happened?”

“I don’t know, but they’re out.”

“What about the guy who took them hostage?”

“I think he’s dead.”

In the days that followed, I learned the hostage-taker was Malik Faisal Akram, a 44-year-old British citizen. Though he had a criminal record in the U.K., Akram had likely never owned a gun before coming to the United States, where hepurchased one illegally just days before he knocked on the locked doors of Congregation Beth Israel, posing as a homeless person and askingfor shelter.

In negotiations with the police, Akram demanded the release of Aafia Siddiqui, an al Qaeda agent who was being held at a women’s federal prison in Fort Worth, about 20 miles from the temple.The hostages escaped after the rabbi threw a chair at their assailant and fled through a nearby exit.Then FBI agents cut power to the synagogue, entered the building and shot Akram dead.

In the end, the gunman’s motives provided little clarity. If anything, they made the act seem more senseless and murky.

Congregation Beth Israel’s rabbi later credited the success of his daring escape to emergency preparedness training he’d received. When a news anchor expressed surprise at this, I thought: Really? Every temple I’ve ever visited had locked doors and security guards. Every single one.

Since my adolescence, I’ve guarded my Jewishness. I wonder sometimes if I’d told no one, stayed in the Jew closet, could I have just skipped this walking identity crisis? Could I have forgotten that part of myselfand essentially passed as status-quo white America?

The answer is, No. I am Jewish. But that isn’t wholly who I am. No one’s identity is as simple or reducible as Black or white or brown or gray. The racist society we live in might make that fantasy a reality, but inside it’s not true. People are individuals ― people are complicated.

Watching the news with my mother on that January night, I remember looking at our dusty mantel. Atop were two Stars of David, a very plain menorah and, right in the middle, a photo of Grandpa Graye and my brother, easily the best image we have of my grandfather. My brother’s not smiling in the picture, and neither is this big Eastern European man with his baggy steeleyes and sad jowls.

He didn’t teach his children or grandchildren about their culture because he believed he was protecting them. In some ways, he was. I used to think such protectionism erased culture, but now I see it can cultivate its own heritage.

Looking at my grandfather in the photo, I saw that the grayness was as much a part of him as it is of me. However our culture may make us feel about it, the grayscale of identity is something to embrace, not dispel. I may never fully know who I am, but that’s OK. That is part of my identity.

Do you have a compelling personal story you’d like to see published on HuffPost? Find out what we’re looking for here and send us a pitch.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies