In Tarrant County eviction court, life-altering decisions are made in a matter of minutes

In eviction court, a case can be decided in a matter of seconds.

When tenants don’t show up to their court dates, the court only hears one side of the story. The judgment, then, is clear. And while the cases roll by quickly, the decisions are of immense magnitude for the tenants and landlords listed on the docket.

On two mornings in early November, the Star-Telegram sat in on eviction hearings in two Tarrant County Justice of the Peace courts. Judge Sergio De Leon called nine cases in less than an hour and a half; Judge Mary Tom Curnutt called about 18 cases in just over an hour and a half.

Many of the cases are for a few thousands dollars — $3,000 or $5,000 in back rent — but there’s a wide range. (In Curnutt’s court, one set of tenants hadn’t paid rent in about a year; they owed $19,893.)

In De Leon’s small courtroom in downtown Fort Worth, he rules in favor of Bell Lancaster & White Buffalo Apartments in the West 7th District, against a tenant who was being charged $2,260 per month for their apartment. In the next case, also uncontested, the judge jokes to the representative of Mag & May Apartments, in Near Southside, that their complex might not be the most expensive in town anymore.

“I think y’all lost the award, they have the highest rent now,” De Leon says, referring to the Bell Lancaster & White Buffalo complex.

Assistance resources

Legal and rental assistance and related resources for DFW area residents. Scroll through the list and tap for more information.

Show more

De Leon decides both the Bell Lancaster & White Buffalo case and the Mag & May case in about a minute. With no defendant, no second side to the story, there was nothing for the judge to deliberate over.

It’s the same in Curnutt’s Arlington courtroom — a more spacious courtroom with long, pale pews and a screen in the front for Zoom appearances. In cases where no tenant has appeared, Curnutt calls landlords or property managers up to her desk and rules with little discussion. In one case, it takes about half a minute for Curnutt to rule in favor of the landlord.

Curnutt moves through the uncontested docket swiftly, but her pace slows when one plaintiff makes an unusual request: the landlord asks the court, even without the tenant present, if someone could put her in touch with the city’s rental assistance program.

The landlord wants the tenant to stay, wants them to get back on track with their rent.

It’s “one of the first times” she’s seen someone walk up with an uncontested case and then step away from the easy judgment, Curnutt says. The judge pauses the case for 60 days and sends the landlord away with a pamphlet. A representative from the Arlington Housing Authority’s rental assistance program, who’s present on Zoom, will be in touch, the judge says.

In eviction court, particularly with the added flexibility of pandemic-time rules and rent assistance programs, so much depends on the landlord. Sometimes, even rulings in favor of the landlord can look poised for different outcomes.

As Curnutt’s court moves into the contested cases, she hears one in which the tenants owe $8,320 in back rent. Curnutt rules in favor of the landlord, but the landlord tells the court that they’ll work with the Arlington rental assistance program and try to sort out the payments.

“They can stay,” the landlord says, if the rental assistance works out.

A few cases later, Curnutt hears a case with a back rent so low that the judge remarks on it.

“It’s my tiniest one today, it’s $1,136, so it’s little,” she says.

But the property manager declines to participate in a rental assistance program — and had previously declined to accept a $1,000 payment from the tenant because it was late.

In this case, Curnutt also rules in favor of the landlord.

But despite similar rulings, the tenants in these two cases have entirely different outlooks. The first set of tenants, owing much more back rent, has a chance of staying in their home. The second tenant, owing a fraction of the back rent, has no such hope.

During the pandemic especially, Curnutt and De Leon are not merely listeners. Throughout their hearings, each of them explains the process to tenants and property managers, each of them calls in the local rental assistance programs.

In De Leon’s courtroom, one hearing stretches on as De Leon asks questions and looks over evidence. In that case, with the tenant owing nearly $4,000 in back rent, the property owner eventually tells the judge why she can’t wait any longer for the rent to come through.

“We’re in our 70s, we depend on this rent for our income, we’re retired,” she says. The property taxes are due soon, she adds. “And I don’t have the money. I need her out so I can rent the house.”

In that case, preexisting rent relief funds complicated the legal ruling. But when a landlord or property manager is not interested in participating in the program, the eviction process moves along.

Tarrant-Dallas eviction fillings

Throughout the pandemic, Texas has not uniformly or consistently enforced federal eviction protections or enacted its own statewide protections. Some Texas cities and counties put their own eviction protections in place. The result has been a patchwork of protections, with varying rules and enforcement standards across the state.

Show more

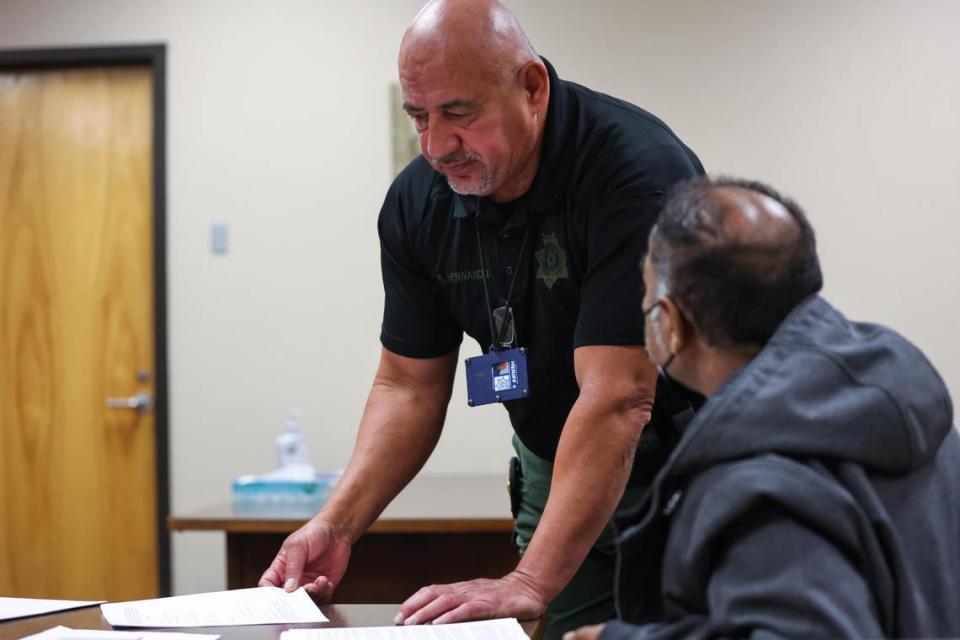

In De Leon’s seventh case of the day, the property manager for Hanratty Place Apartments sits at one desk facing the judge and the tenant sits at the other. It’s just the two of them at those desks — no attorneys to speak for them, no family members for moral support.

The property manager starts, outlining the situation: the tenant is in a subsidized apartment, and owes $351 per month. The tenant hasn’t been paying, and she now owes back rent totaling nearly $4,500. The property manager is not interested in participating in a rental assistance program.

De Leon turns to the tenant and asks for her side.

She admits to the primary points of the case. It’s cut-and-dried. De Leon rules in favor of the apartment complex, ordering the tenant to pay the $4,500 in back rent and permitting the property manager to take back the apartment. Any questions? De Leon asks.

The tenant speaks up, a clipped sentence. “What if I do not have somewhere to go?”

It takes a moment for De Leon to respond.

“That is a tough and very serious question,” he says. He calls in the Fort Worth city employee who’s sitting off to the side, and asks her to help the tenant find resources.

The tenant will have at least six days to answer her own question, before the property manager can repossess the apartment and remove her from the premises.

As the tenant and the city employee walk into the hallway, the judge calls the next case.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies