All talk? Can Columbia turn dreams into action or will it fall further behind other SC cities?

Columbia is a city caught in the middle, literally and figuratively. Sandwiched in the middle of South Carolina between two cities — Greenville in the Upstate and Charleston in the Lowcountry — that have seen much faster population and economic growth, Columbia is caught in neutral, in a sense.

The capital city certainly has its bonafides. It is the seat of state government, home to the Palmetto State’s flagship university, hosts the nation’s largest Army basic training installation, and has seen a revitalization of its downtown.

But it also has been dogged by relatively stagnant population gains, middling job growth and a property tax structure that bewitches some business leaders.

At the same time, Columbia has big ideas — some of them long-held — on how to progress, shift itself out of neutral and into cool-capital-city gear. The city has got to “activate” its sparkling riverfront, many residents and leaders have said for ages, and still say. Many of them also say: It’s got to put statement-making developments at important intersections. It’s got to solve its high property tax problem. Connect the city’s districts. Expand the convention center. Restore Finlay Park. Get an Apple store. Convince local college grads to start careers here. Prove that Columbia’s a great city.

Columbia’s got big dreams. It talks a lot about the city it wants to be.

But Columbia’s future hinges in large part on whether it can get past talking about so many of its long-held dreams and actually execute on them. Will South Carolina’s capital progress at a snail’s pace? Or can the city turn talk into action and turn Columbia into a Raleigh or an Austin?

“We all wish for the best. We all wish to have an inclusive, innovative, engaged … strong, welcoming, vibrant city. We’ve done a lot of the wishing,” said Roslyn Clark Artis, who for the past four years has served as president of one of the city’s half-dozen places of higher education, Benedict College. “I often find myself in these four years questioning whether there’s the political will, the social will, the economic will to create the city we wish for.”

If wishing can turn into a willfulness to put in the work, Columbia can turn into that city that people keep talking about, Artis and others believe.

“In 20 years we’re going to be the city on the hill in South Carolina, mark my words,” said Jared Johnson, a 34-year-old resident of the Old Shandon community who, in many ways, represents a grassroots class of Columbia changemakers.

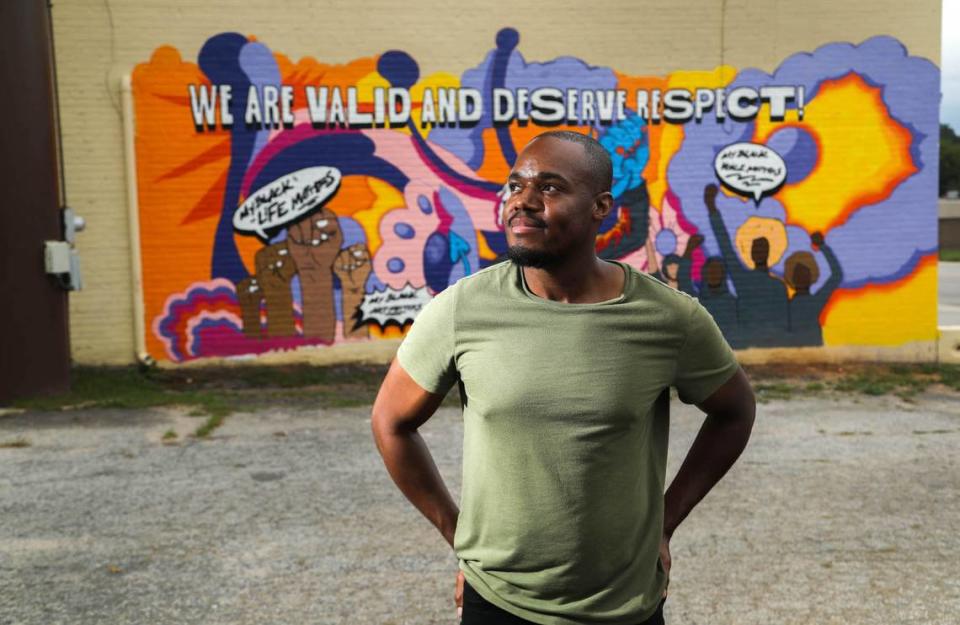

Johnson is a University of South Carolina graduate. He works two jobs. He’s active in his neighborhood, from organizing events to sparking political dialogues online. Last summer, he started a push for a “Black Lives Matter” mural to be painted in the city. He’s among the Columbia residents who are investing themselves in creating the capital city of the future.

“We have dreams but, like, are we going to work toward our potential, or will we continue to see some things we’ve seen in the past?” he wonders.

Like Johnson, many people in Columbia, from the neighborhoods to the office towers to City Hall, agree the city has great assets and great potential. What Columbia looks like 20 years from now will depend on how the city harnesses today’s opportunities and turns talk into action.

“You’ve got to get to the point where you’re not just waiting for the change. You’ve got to be the change you seek,” Johnson said.

FALLING BEHIND

There was a time, not all that long ago, when Columbia was the most populous city in South Carolina.

But those days are gone, at least for now.

Charleston, with its robust tourism industry and nearby manufacturing behemoths like Boeing, has surged in the last decade to become the state’s largest city; it’s grown by more than 25% in a decade. Meanwhile, Greenville, with its gleaming downtown district bursting with new restaurants and shops and residences, saw its population grow 21% in 10 years.

But Columbia has had much more modest gains. The population in 2020 was 136,632, up just 5.7% gain in the last decade.

Columbia Chamber CEO Carl Blackstone lamented Columbia’s slipping in the population rankings. He said the city needs to add more jobs and create an entrepreneurial environment to stoke the flames of growth.

“These other cities have lapped us,” Blackstone said. “And look, I don’t want Columbia to be Atlanta. I don’t want us to have the traffic issues that Charlotte has. I want us to be uniquely Columbia. But we need the job growth.”

Richland County touted a stellar economic development year in 2020, reporting more than $630 million in new industrial investments and the announcement of more than 1,300 new jobs. It was the most economic investment the county has seen in a single year on record.

But Blackstone notes that new economic announcements have been few and far between in 2021, and he also points out that the Upstate’s Spartanburg County, rich in the automotive-related jobs that dominate the I-85 corridor, had $1.2 billion in announced economic capital investment the first six months of 2021.

Third-term Columbia Mayor Steve Benjamin, who is not seeking re-election in Tuesday’s election, recognizes the inevitability of people comparing Columbia to its peers in the Upstate and Lowcountry. Still, he notes the constant talk of Charleston and Greenville is not a one-to-one comparison.

“Columbia is different than the rest of the state,” the mayor said. “We just are. Literally, in our DNA from our founding as a city, we were founded as a government town. We were founded as a capital city and a place where the state’s toughest discussions would be had and the toughest fights would be fought. … We are the capital, and it is part of who we are.”

WHY IS COLUMBIA’S PROGRESS SO SLOW?

Columbia can boast about some progress. But for years, the city also has been driven into gridlock on certain issues — things that Columbians have talked about for years on end with little remarkable change, particularly when it comes to business and development.

For instance, the former Kline Iron and Steel property — 4 acres of vacant land at the corner of Gervais and Huger streets — has been whispered about for redevelopment for years, but nothing has happened. And the old Capital City Stadium site on south Assembly Street has had a more than decade-long crawl to redevelopment, though plans are inching forward to turn it into apartments and retail.

Progress happens relatively slowly in Columbia.

“Columbia does have a lot of harsh red flags,” said Sara Middleton, the daughter of prolific Columbia developer Scott Middleton. The Middleton family played a major role in revitalizing the 1600 block of Main Street in recent years, and their newest business ventures include a north Columbia brewery that’s expected to become the state’s largest. Sara Middleton herself fell just short of a City Council seat in 2019.

“I’ve met with hundreds and hundreds of business owners, local and people who have tried to come and invest here but couldn’t,” she said. “Why not Columbia? I kid you not, most of the time I get the answer, and people kind of laugh, ‘They just make it absolutely too difficult to invest there. Oh, and their taxes are ridiculous.’”

If it weren’t for their local roots, the family might have been driven out of Columbia to pursue development ventures elsewhere because of the hurdles they’ve faced to develop in the city, from the planning department to the tax bills, Middleton said.

“It should never be that way to bring resources and taxpaying dollars to the city,” Middleton said. “It should never just be this kind of unnecessary red tape.”

Ryan Coleman, the city’s economic development director, agrees that the city’s taxes are too high and development regulations can be too cumbersome, which toughens his job of attracting major retail and new industry to the capital city.

“I’m not saying you’ve got to be the cheapest and fastest city in America, but you can’t be last, and you at least need to be in a competitive place,” Coleman said.

There are more reasons why the pace of progress in Columbia seems to run slow, community leaders and residents have said. Those include the sometimes fractured and competitive nature of investments and improvement efforts. While resources are poured into areas like Main Street and BullStreet, other parts of the city, such as the Two Notch Road corridor, seem left behind.

Competition among different regions of the city and imbalance of resources leads to unequal development in parts of Columbia, Artis, the Benedict College president, noted. There are two Columbias, she said; one that’s growing and thriving, and another that’s “under-resourced” and hurting.

“If we’re not intentional to say that we’re one Columbia, if Two Notch isn’t thriving, then Columbia is failing,” Artis said. “There are communities that have been left behind. … We’re not one Columbia. It starts with an honest acknowledgment that there are certain segments of Columbia that are not able to thrive.”

In Columbians’ quest for a brighter city, residents’ efforts are sometimes thwarted by official barriers, even for something as simple as painting a mural proclaiming the inherent value of Black lives or hosting a neighborhood movie night in a public park, Jared Johnson noted.

In the summer of 2020, when a wave of racial justice activism spurred bold “Black Lives Matter” murals in downtowns across the country, including Charlotte and Washington, D.C., Johnson rallied support from the Rosewood neighborhood and beyond to paint a similar mural on a street near the Owens Field airport south of downtown. But while paint quickly hit the pavement in other cities, the effort languished in Columbia — state transportation regulations and a lack of political will kept it from happening, Johnson said.

More than a year after the initial idea, Johnson’s mural eventually came through — with some guidance from the city’s One Columbia arts organization — in a place where it didn’t need city approval. It was just recently unveiled on the side of a private bakery in north Columbia.

“This is interesting that leadership and individuals in the traditional realm will make you wait for months to get something positive done, whereas businesses and grassroots (efforts) are quick to say, ‘Let’s get it done,’” Johnson said. “We could afford to be more flexible, more innovative. … Let’s not put roadblocks on, whether it’s me or you or anybody who wants to make the city shine.”

AGREEMENT ON PROBLEMS, NOT ON SOLUTIONS

Few people disagree about many areas where the city needs to make progress. What the city lacks, however, is a common vision on how to solve many of its problems.

Take for instance:

▪ Property taxes in the city, particularly for businesses, are notoriously high compared to faster-growing cities: twice as high as Charleston and 1.5 times as high as Greenville. A recent tax study concluded the area’s taxes, which include those levied by the county and schools, have stymied growth. Some solutions have been suggested — such as combining city and county services, lobbying the state Legislature to change part of the S.C. tax code, and financial cooperation between Richland County’s two school systems — but nothing has been implemented.

▪ The city struggles to retain its well-educated, talented college graduates, particularly from the University of South Carolina, home to some 30,000 undergrads, even as the university benefits from city resources and holds sizable leverage in the city.

The so-called “brain drain” troubles Steve Cook, who owns multiple restaurants in Columbia and leads the Five Points Association board, a merchants group for the popular downtown district.

“We need to keep some of these university students,” Cook said. “The university is, no doubt, a huge part of downtown Columbia, specifically. But too often, these folks come in from out of state, spend four years here, then, boom, they are gone. Back to Charlotte, Atlanta, wherever.”

▪ Then there’s Finlay Park, which presents a different sort of problem and the perfect center of a Venn diagram where Columbia’s past, its present and the unrealized promise of tomorrow converge at once.

Once considered the “crown jewel” of the city’s parks, the 18-acre expanse downtown off Assembly Street has been in disrepair for years. The picturesque spiral fountain on the north end of the park — long used in promotional images of the city — hasn’t been functional in years.

The City Council for nearly two years has considered an $18 million overhaul of the park, but that work has not yet begun.

Joe Taylor has seen Columbia — and even The State newspaper — circle the same projects and the same issues in the city for decade after decade, from economic development opportunities to underperforming schools to, yes, fixing Finlay Park.

“It’s almost a hoot,” said Taylor, who, sitting in his West Columbia office, pointed to a 2005 special edition of the newspaper that highlighted projects that could define the future of Columbia, including building out BullStreet, developing along the riverfront and improving Five Points — the majority of which are still in progress or still being talked about. “We go from new deal to new deal to new deal.”

A former state Secretary of Commerce, Taylor has long been a critic of what he sees as barriers to new investment and progress in Columbia. He’s also set to get a major voice in rectifying those barriers: Taylor is the only candidate for Columbia City Council in District 4 in Tuesday’s election, meaning he likely will secure the seat.

He’s adamant about making it easier to get permits and other bureaucratic necessities to move along new businesses and developments. He also said the capital city needs a strong voice to recruit new development. And he said Columbia should be looking for more ways to leverage its relationship with the University of South Carolina.

“We’ve got nobody selling Columbia,” Taylor said. “Nobody is selling this town. When you have the assets, when you have a university where there are more than 30,000 students, that’s an opportunity that very few other communities in America have.”

Creating a city that’s not still talking about the same problems 20 years from now isn’t so easy, in part because Columbia has a unique political culture that makes it hard to just get things done.

“For whatever reason, people in this town don’t play nice,” Cook said. “There are so many factions. You’ve got the university and the city government and private developers. If the people who make a difference in the city and the people who have the wherewithal got together and said, ‘This is what our vision is,’ we’d see major change for the future.”

As it is, Cook says Columbia is “so freakin’ dysfunctional.”

Merrell Johnson, who works for a local mental health nonprofit and is a city ambassador for the local tourism bureau, laughs when asked whether the various factions in Columbia are likely to get on the same page about how to move forward.

“Have you ever tried to plan a lunch with 10 people?” he asked. “No one agrees on the same thing. What is our population now? Almost 150,000? (Agreement) is not going to happen. But, as we move forward, it is important to get the public’s input. I’m a firm believer of the process of listening to what people have to say.”

But Benjamin notes very little of the city’s progress in the last few decades has come without a fight. And it is worth fighting for the things that will move the city forward, he said.

“They were all fights,” the mayor said. “Baseball, fight. BullStreet, fight. The Palmetto Compress, fight. The Hub, fight. Soda City, fight. Student housing, a fight. None of these things were easy. Folks think they’re all walks in the park, and we had to fight for each and every one of them.

“You lead, you spend time consensus building, and then at some point you have to act and do something.”

Mission 2041: Make Columbia proud of Columbia

For all its still-unmet goals, Columbia, to be certain, has made big strides in recent years. There have been a host of new private student housing complexes built across the city, particularly near the University of South Carolina, that have altered the city’s skyline.

Notable progress has been made at the BullStreet District, where the city and Greenville’s Hughes Development are overhauling the 181-acre former state mental hospital site in one of the biggest commercial development projects on the East Coast. Multiple construction crews are working there daily, building an office building, apartments and parking garages.

Those buildings will join the Columbia Fireflies minor league baseball park that opened in 2016.

And the Main Street District downtown has seen laudable change — tripling the number of residents living downtown in just eight years and becoming a regular destination for festivities including the weekly Soda City market each Saturday. It’s added new restaurants, bars, a theater and hotels in recent years, with more businesses on the way this very moment.

As a whole, the city reported $1 billion in active building investments for multifamily residential, office, retail and industrial developments between January 2020 and March 2021.

So sure, Columbia has its challenges. But the city’s bonafides don’t lie. For those reasons and more, Merrell Johnson doesn’t want to hear anything more about Greenville and Charleston.

He’s grown tired of the comparison game between Columbia and South Carolina’s other two hot spot cities.

“I hate that question,” Merrell Johnson said. “We are not a Greenville, and we are not a Charleston. When you think of Greenville, they are very much oriented around business. When you think of Charleston, they are very much oriented around tourism. Columbia has always been and will always be focused around government and higher education.”

A lot of people agree with Johnson. It was a sentiment basically agreed on by all four Columbia mayoral candidates — Moe Baddourah, Tameika Isaac Devine, Sam Johnson and Daniel Rickenmann — in a recent forum.

If the people, businesses and government of Columbia will actively work together to push the city forward, “then we can truly be competitive,” said Coleman, the city’s economic development director. “We need citizens who want to be in Columbia and make this city all that it can be, who are going to show up to events, who do things in the community, who are going to help grow this place.”

At this moment, Coleman said, “Columbia is in a put your money where your mouth is situation. … What you’re seeing happening right now and the good things that are happening are just a fraction of what we can achieve in 20 years if we get our stuff together and attack it in a very head-on, coordinated manner.”

Merrell Johnson said Columbia should aspire to be like other state capital cities that are thriving, specifically pointing to Raleigh, North Carolina. He wants to see the kinds of change that will make Columbia should feel more like home for young professionals like him, including investments in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, and diversifying the ways people can experience the city.

Cook, the Five Points Association leader and restaurateur, talks about the same kind of progress, especially when it comes to public transportation throughout the city.

“To me, that’s the future,” Cook said. “The public transportation infrastructure is probably not there (now), and getting some of that stuff more in line with bigger cities I visit, where you can literally live downtown without having a car, is critical. ... If we stick with the way we are ... we are going to be left in the past a little bit with that.”

Blackstone, the Columbia Chamber leader, says the capital city should aim to be the “best Columbia it can be.” But he says that work needs to start now, particularly in the realms of job growth and streamlining the local economy for new business.

“What does Red say in ‘Shawshank Redemption’?,” Blackstone said, referencing Morgan Freeman’s line in the classic film. “‘You either get busy living or get busy dying.’ We’ve got to get busy focusing on that 20-year future, or just recognize everybody else is passing us by and it’s going to be harder to come out of this thing years later. If you’re not growing, you are dying.”

Benjamin says Columbia needs to be deliberate in looking toward the future. And, in his view, that includes saying “yes” to ambitious, even controversial, deals like overhauling the BullStreet property (a long-fought gamble), or looking to expand the Columbia Metropolitan Convention Center (a new battle brewing).

“You can’t be all things to all people, but you do have to have a very intentional strategy to become the Columbia of 2031 and 2041 that you desire to be,” Benjamin said. “You just have to be willing to say ‘yes’ sometimes.”

“I hope that in 20 years from now that every single person who lives in the city is an unabashed, vocal advocate for what makes this place special,” the mayor added. “Columbia is more diverse than any other city in the state. It’s a special place. I’m biased; it’s given me everything I have in life, from a family to a career to opportunity and everything else. But I don’t know what we shouldn’t be talking about, but I can tell you what we should be talking about.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies