I sued Harvard to save my slave ancestors' legacy. Black people own rights to US history.

In January 2010, I lost my mother, Mattye P. Thompson Lanier.

She was born to sharecropper parents in the small agricultural community of Mount Meigs in Montgomery, Alabama. She was a proud woman who loved and adored her family. She graduated from a historically Black college in Alabama and later worked as a teacher and principal.

But more important, she was the keeper of our family’s oral history. She often remarked of her experiences growing up in the Jim Crow South, describing her community as the cradle of the civil rights movement. And she was reared by her extended family, which included her grandfather, a former enslaved man named Renty Taylor Thompson – a descendant of Papa Renty, who was born in Africa and brought to America in chains.

Some of my mom's last comments to me were about documenting the story of Papa Renty – the first in a line of many men named Renty in my family. He was forced into bondage and, like many slaves, sold by whites in their quest to profit from human suffering.

I've never broken a promise to my mother.

So after she died, I set out to learn as much about my family history as possible. In the process, I sued Harvard University and found allies in the most unexpected place —among the descendants of the man who ordered the abuse of my family.

My lawsuit kicked off one of the most controversial questions in America's reparations fight: Who owns the rights to the pillages of slavery?

Different sides of history

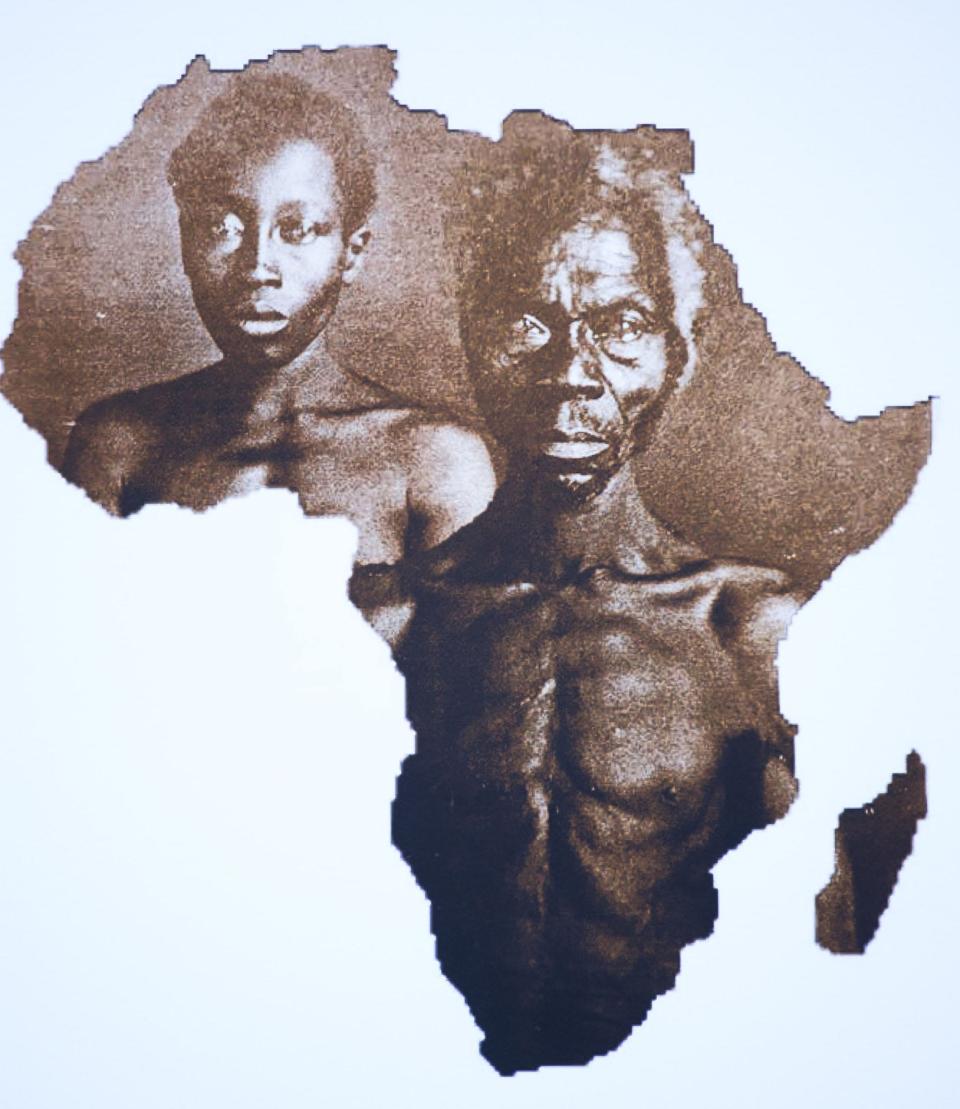

In 1850, Harvard professor Louis Agassiz commissioned partially nude images of African-born enslaved men and women. Pointing to their stark physical differences, Agassiz theorized a racialized science that alleged Black people were a separate and inferior species.

My great-great-great-grandfather, Papa Renty, was one of them. So was his daughter, Delia.

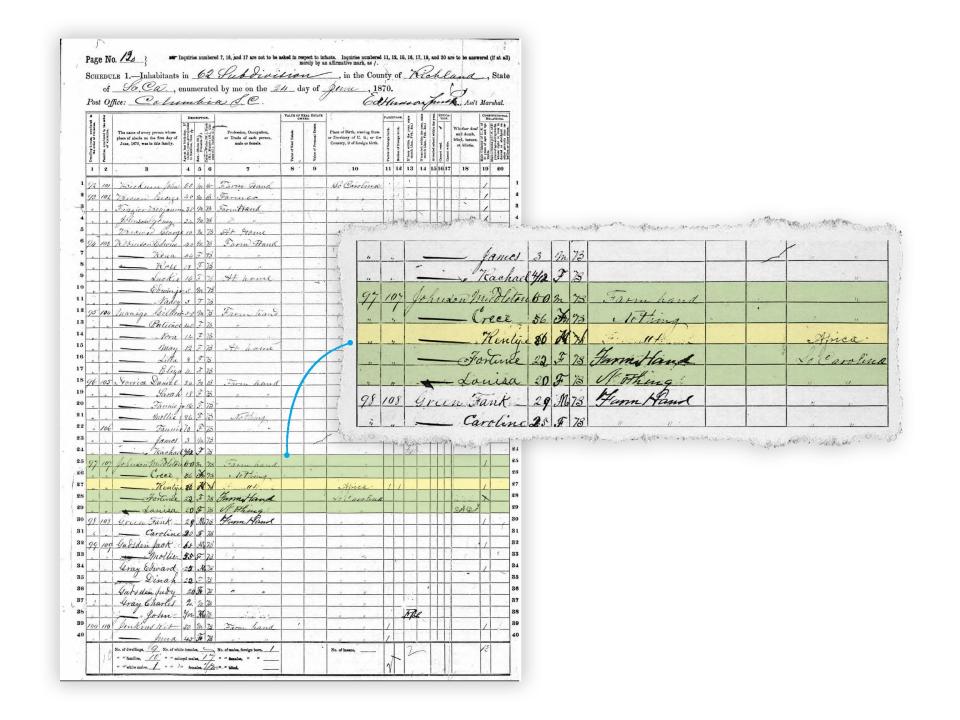

I found slave indexes and cemetery records that place my family on land owned by slaveholder Benjamin Franklin Taylor. The documents offer what is, in my view, a direct lineage from the man in the image to me.

In 2011, I appealed to Harvard officials to look into my research and confirm that I am Renty’s great-great-great-granddaughter. They did not. But even more important, I asked that the full and rich legacy of Papa Renty be presented to the public. It was not.

Every time I looked at the Agassiz photo, I was reminded of the stories I heard about Papa Renty growing up: He was strong willed, a bit hard headed and determined.

I kept fighting.

An unexpected connection

The note from a woman describing herself as Agassiz's great-great-great-granddaughter landed in my Facebook messenger app on March 23, 2019, at 9:34 p.m. She stated that she "wants to see justice and liberation made real. I was trying to see how I might be of service to y/our cause."

I had been afraid to click on the message. It was just three days earlier that I had filed my initial lawsuit against Harvard University in Massachusetts Superior Court, Middlesex County, demanding ownership of the exploitative photos of my ancestors. Since then, I had been flooded with negative comments, threats and harassing messages. I couldn't handle another troll.

It turns out Marian Moore wasn't a troll. She was a force and a social justice advocate. She asked whether she could pay for my legal fees. While I didn't need help in that area, the support she and her family provided was even more of a saving grace.

I met a handful of the Agassiz descendants on a Zoom call. They had a plan to push Harvard to right the wrongs of their ancestor's actions. More than 40 of them signed a letter to the president of the school asking that the photos be relinquished so the university could begin to "make amends for its use of the photos as exhibits for ... white supremacist theory."

Three months after I filed my lawsuit, Marian and her sister, Susanna Moore, joined me for a news conference on Harvard's campus and pushed their way into the building that housed the president's office to deliver the family's letter. I was initially stopped from entering by authorities. Those same authorities allowed Marian and her sister to walk through with little to no resistance. They were determined. I was terrified.

I spent time on a plantation in Louisiana with Marian and several other members of the organization she works for, Jubilee Justice. The group is dedicated, in part, to bringing equity to Black Americans whose families were exploited on Southern land.

I immediately felt comfort and compassion in her voice.

Being on that plantation was a learning experience for me. Being in spaces I know enslaved people once occupied is difficult. I replay what potentially might have happened in the rooms where people were victimized.

That trip was a chance for me to strategize with Marian about Harvard.

The family history I knew

Throughout my childhood, family time on Sunday afternoons was usually reserved for reflections: “Always remember, we are Taylors, not Thompsons” is usually how the conversations began.

As a child, my mother listened intently to the stories told by her formerly enslaved elders. They always began with the patriarch and Black African, fondly referred to as Papa Renty.

He was literate, according to my family's oral history. He also taught others to read. He read the Bible and taught other slaves from it. He went to church, but also worshipped in secret when he could, holding on to spiritual traditions from his native Africa.

For my mother, these stories were a source of pride. Education was important to her.

I also grew up hearing about Tena, the mother of the third man named Renty in my family. She was known for being bossy and moved between South Carolina and Alabama. Her name was one of many I found in slave records in Charleston.

My mom talked about African medical traditions and roots that were used to cure illnesses. She knew about them because of the stories that were shared over generations.

Why didn't Harvard reach out to get those stories? The university published a book in 2020 and hosted a 2017 symposium using these images that mischaracterize and marginalize my enslaved ancestors.

Harvard suit and white supremacy

I've since taken Harvard off that pedestal of premiere academic institution. When Ivy League schools speak, the world, sadly, believes them. Harvard used its academic and scientific prominence to subvert Black life and legitimize white supremacy.

The school denigrated the legitimacy of Papa Renty’s heritage. It's a legacy that's established by the rich and detailed history passed down to me through generations. But more than that, Harvard commissioned and acquired these images illegally. The daguerreotypes are the plunders of slavery, taken without permission.

Scroll down to read Lanier's legal complaints and the judge's decision

In response to my suit, Harvard stated that a picture, irrespective of how it is acquired, is the property of the photographer. It also stated that the subject has no interest in the image even if the image was the outgrowth of a violent act or crime.

In March, the Massachusetts lower court found in Harvard's favor, dismissed the case and ruled that Renty and Delia, as crime victims, have no “property interest” in the daguerreotypes.

The descendants of Agassiz – Marian and Susanna – were supporting me online. They had listened, just as I did, to virtual hearings. They seemed shocked by the ruling. I was not.

I remember them questioning how a case that so clearly showed Renty was my ancestor, and so strongly demonstrated Harvard's lack of humanity, was found in favor of a university that had not only sanctioned the infraction of slavery but also seemed to maintain a disregard for its history of exploiting others.

And I remember thinking about this nation's long history of resistance to recognizing rights of Black Americans.

For many reasons, but particularly because what happened to Renty and Delia were crimes against humanity, I appealed to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, which agreed to hear the case. Harvard fought back against our appeal by equating the photos of Renty (in court documents) to Civil War battlefield images that changed public perceptions, some of which may have previously romanticized the war.

I look forward to my attorneys, two of whom are Jewish and one of whom is Black (descendants of Holocaust survivors and enslaved men and women respectively), seizing Harvard's cultural insensitivity as a teachable moment to educate the most well-known academic institution in the world.

No, Harvard, we will not allow you to retain the property of my ancestors and steal their stories. And no, Harvard, we will not allow the institution that helped birth white supremacy to expropriate the property of the formerly enslaved and appropriate their stories.

On Nov. 1, the matter will be before the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, and I will be standing on the shoulders of giants for the legacy and lives of Renty and Delia.

I hope to be standing next to the descendants of Agassiz.

This will be the Massachusetts court’s Brown v. Board of Education moment. This is a groundbreaking reparations fight that has the potential to change the way this nation sees the rights of Black Americans and our historical legacies. I hope that the court will recognize right as well as reality by acting boldly in upholding the laws of the commonwealth.

Tamara Lanier is a retired probation officer who has been active in the Connecticut chapter of the NAACP. Find her on Twitter @tamaralanier

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: I sued Harvard University to save my slave ancestors' legacy

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies