We studied 40,000 pieces of litter to find out where it all comes from – here's what we discovered

Litter is perhaps the most tangible of all environmental problems. And it’s not just a disrespectful few who are responsible for it. Litter, defined in its broadest terms, includes any solid material present in the environment that was made or processed by people. It may have arrived there from an accidental spillage, as debris washed ashore, or because of the irresponsible management of industrial waste.

How some types of litter enter and travel through the environment cannot be traced. Litter breaks down beyond recognition, identifying marks such as branding wear away and rivers can transport it far from where it originated. But some litter has clear sources and pathways, discernible from its function and packaging labels, from which the brand that made the item can be easily identified.

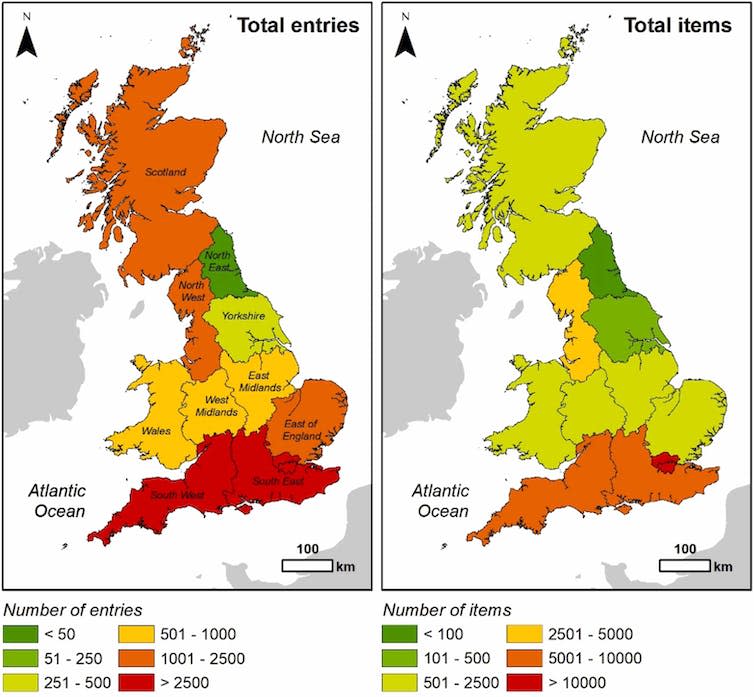

The community interest company Planet Patrol created an app for people to record the litter they find and remove. We used it to map the location, materials, type and, where possible, brands of 43,187 items of litter collected across the UK in 2020. Our research was recently published in the Journal of Hazardous Materials.

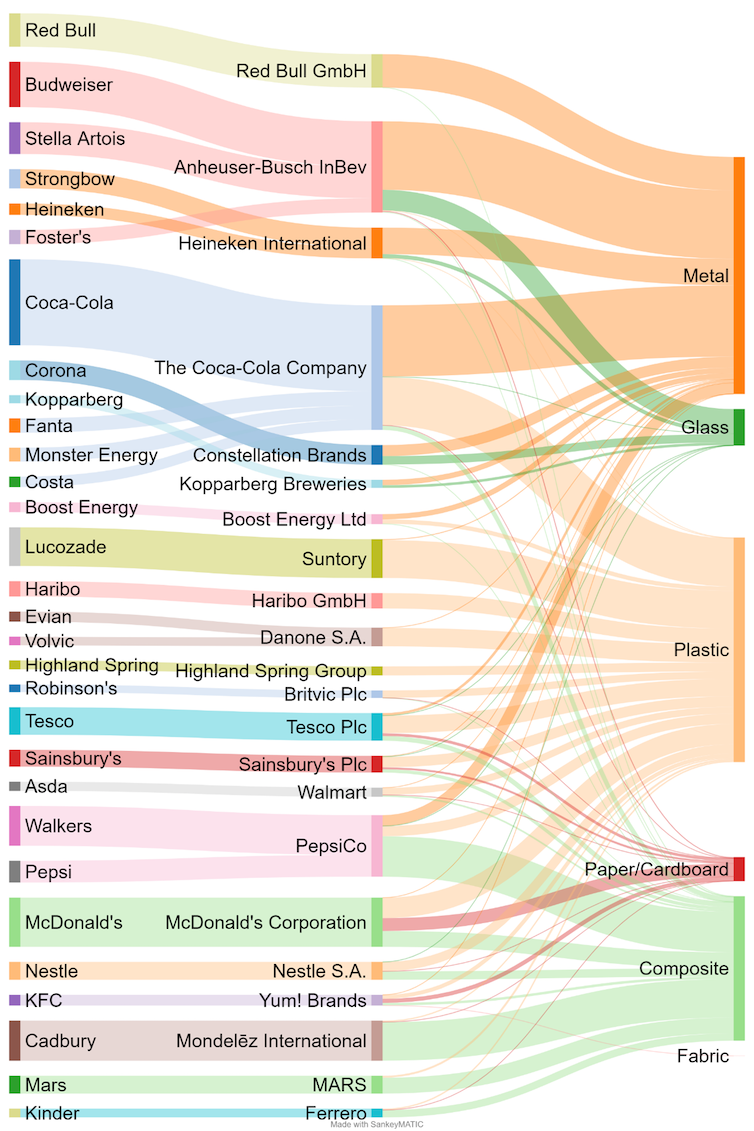

Plastic was the most common material recorded, accounting for 63.1% of all items. Metal was second (14.3%), followed by composite materials (pieces of litter made from more than one material, like Tetrapak cartons) at 11.6%. Bottles, lids, straws and other items from the drinks industry made up 33.6% of the total, of which metal cans were the most common.

Our citizen scientists identified brands for 16,751 items (38.8% of the total), with 50% of these belonging to just ten brands. The Coca-Cola Company was the most frequently identified brand (11.9% of branded litter), followed by Anheuser-Busch InBev (7.4%) and PepsiCo (6.9%). The top three brands were all drinks manufacturers.

Plastic policies

Surprisingly, our findings do not vindicate one of the EU’s most important orders on litter: the 2019 Single-Use Plastics Directive. This identified the top ten types of plastic litter based on beach surveys around Europe, and legislated to reduce their production and sale in the EU while the UK was still a member.

These ten items, which include cotton buds, plastic bags and plastic bottles, were not all common in our results, which came from sampling inland areas as well as some beaches. Though this directive applies to the whole of the EU, we suspect its focus on coastal environments alone does not accurately reflect the nature of most litter found across Europe.

Throughout the 2020s, the UK government and its devolved powers will introduce or reform legislation to tackle litter. These include a plastic tax (introduced in April 2022), a tax on the production of plastic packaging containing less than 30% recycled plastic, a deposit return scheme for drink containers (limited to plastic containers only in England) and reforms which will make packaging producers pay for action including litter picking and education campaigns. Over the same decade, the top ten companies identified by our study plan to change the materials they use in their packaging.

Our analysis of these corporate and legislative policies concluded that they disproportionately favour solutions based on recycling, with little consideration of how to reduce waste and allow people to reuse items. This approach fails to address plastic pollution’s root cause: selling things people don’t really need.

Should we name (and shame)?

Since most litter in the environment cannot be traced back to its origins, naming the people and organisations responsible may seem futile. But litter that can be linked with an industry or a company is some of the easiest to address. This is particularly true for packaging, which made up 59.1% of the items logged in our study.

Given how common this type of waste appears to be, expanding opportunities for people to refill containers with goods (where appropriate), removing or reducing the need for new packaging as zero-waste shops do, is a good idea. This will require collaboration between companies, industries and governments. Small-scale efforts to achieve this are underway, with Wales pledging to become the first refill nation (where people can easily refill water bottles, making bottled water obsolete), some supermarkets introducing or trialling refill aisles and The Coca-Cola Company’s various small-scale efforts to allow consumers to refill bottles with beverages, most notably in Latin America.

Making it easier for people to refill packaging would also reduce demand for raw packaging materials, lower transportation costs and emissions and reduce waste. It will also help people reckon with their own environmental footprints.

Tracing and curbing litter requires foresight and collaboration, which is currently lacking among companies that profit from the waste-generating consumption of single-use products, and the legislators that fail to properly govern it. Naming them is the start of holding them accountable.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Thomas Stanton works with Planet Patrol on a voluntary basis. He received funding from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI).

Matthew Johnson is a trustee of the Clean Rivers Trust, a charitable organisation working on environment pollution.

Antonia Law and Guaduneth Chico do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies