‘A story worth telling.’ This exhibit in Little Haiti pays tribute to queer Black Miami

Drag queens dressed in colorful gowns hold a mock wedding to raise money for a local Black church. At a Miami club, a popular drag king entertains hordes of people. Local newspaper editorials call for an end to LGBTQ discrimination. And queer couples fall in love.

These aren’t stories of Miami today. They’re glimpses of Miami’s Black LGBTQ history dating back to the 1940s.

“Give Them Their Flowers,” a new exhibition at the Little Haiti Cultural Center Art Gallery, displays and celebrates Miami’s under-documented Black LGBTQ community at a time when Florida’s government has become increasingly hostile toward Black and LGBTQ representation.

The project, on view until April 23, is the most relevant exhibition in Miami right now.

“This is a space that celebrates, honors and makes visible what has always been here,” said Nadege Green, the exhibition’s co-curator and founder of historical storytelling platform Black Miami-Dade. “There’s something that happens, especially around LGBTQ+ folks, where sometimes you feel like you remain invisible, and this fully rejects that.”

“We’re here, we’re queer, we’re Black in Miami,” she added. “And that is a story worth telling.”

Since the show was years in the making, it wasn’t meant to be a response to the current political moment, said Marie Vickles, the curator-in-residence at the Little Haiti Cultural Center who co-curated the show with Green. Still, Vickles said, the show underscores the importance of researching Black, queer Floridian history. On Saturday, Green will host a lecture at the Lemon City Branch Library about the project and its findings.

“It feels right on time,” Vickles said. “It’s not so much about responding to the vitriol that’s currently out there, but really just showing that queer folks have been here and these are their histories.“

Filling in the gaps

Green didn’t plan on a curating an entire exhibition at first.

A couple years ago, Corey Davis, Green’s friend and the co-founder of Maven Leadership Collective, asked her if she was planning on a series for Black Miami-Dade about Miami’s Black queer history. Green started to look into it, but “what I found was lacking.”

Sure, there were some records of Black queer celebrities -- like dancer Josephine Baker and drag king Stormé DeLarverie -- performing in Overtown when it was known as “the Harlem of the South.” But besides a few newspaper clippings, arrest reports and event posters, there was very little written material that documented the day-to-day lives of the queer community in Miami’s Black neighborhoods.

“And that is where oral histories fill in those gaps,” Green said. “I was like, ‘I need to talk to people.’ Just because the historical records of old newspapers and archives don’t reflect this, it doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. It just means no one really thought to record it.”

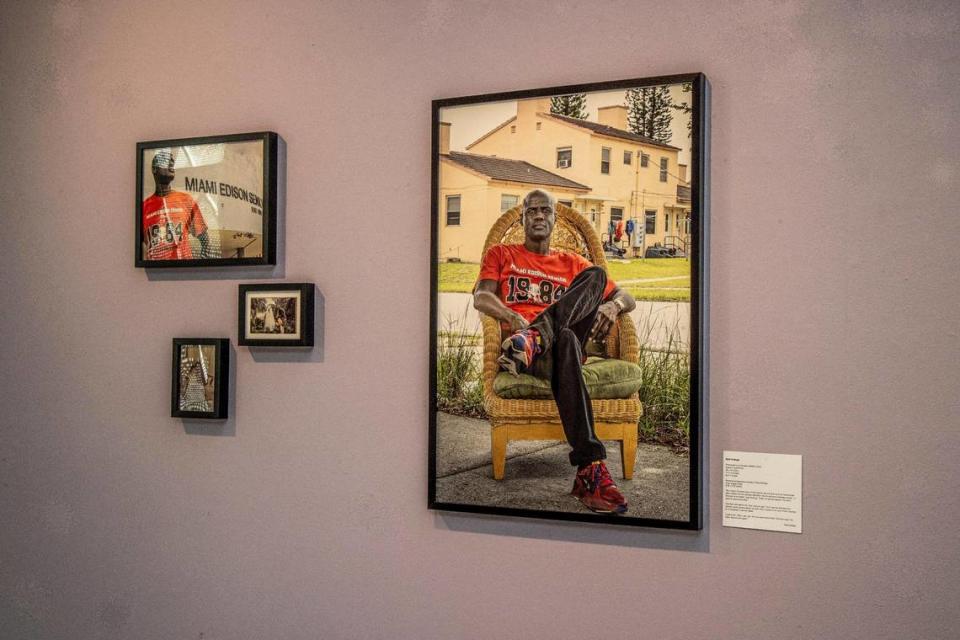

For the next two years, Green reached out to Black queer Miamians all over the age of 40 to talk to them about their lives. She worked with Miami-based photographers Vanessa Charlot and Woosler Delisfort to take portraits. She pulled documents from archives. Eventually, Green had accumulated so much information, she needed a place to put it.

That’s when she reached out to Vickles, who was immediately on board. The show features artwork all by Miami-based or raised artists: Charlot, Delisfort, Kendrick Daye, Hued Songs and Loni Johnson.

Honoring the present

The name of the show, “Give Them Their Flowers,” was inspired by a common saying in the Black community. “Don’t wait to celebrate people when they die,” Green explained. “Honor folks, honor all that they are, while they’re still with us.”

The first thing visitors see when they enter the gallery is a wall of flowers. It’s meant to let people know that this is a celebratory space.

The show is divided into three sections that focus on the present, the past and the “repast.”

The first section features portraits from Black LGBTQ Miamians who recounted their experiences growing up, dealing with segregation and partying with friends. On the lavender-painted walls, couple Frederica Dawson and Barbara Horne hold hands and share photos of their wedding. A jersey belonging to former WNBA Charlotte Sting player Tracey Reid hangs next to her portrait.

Green recalled conversations she had with Naomi Ruth Cobb, 69, a retired cultural anthropologist who grew up in Liberty City during the Jim Crow era. Cobb remembers the physical wall that separated Black and white neighborhoods in Miami.

And Cobb remembered the fun times, too. She used to get barbecue with her dad and watch as drag queens wearing towering heels walk across the street to a spot called The Pool. Sometimes, the queens would stop to chat and eat ribs with Cobb and her dad. At the time, Green said, drag queens were referred to as “female impersonators,” and some were likely to have been transgender women.

A quote from Cobb is displayed next to her portrait. “With my coming out, I started hearing these stories about people being ex-communicated from their families, and here I was with family support,” she said. “Here I was with all this queer love around me.”

Searching for the past

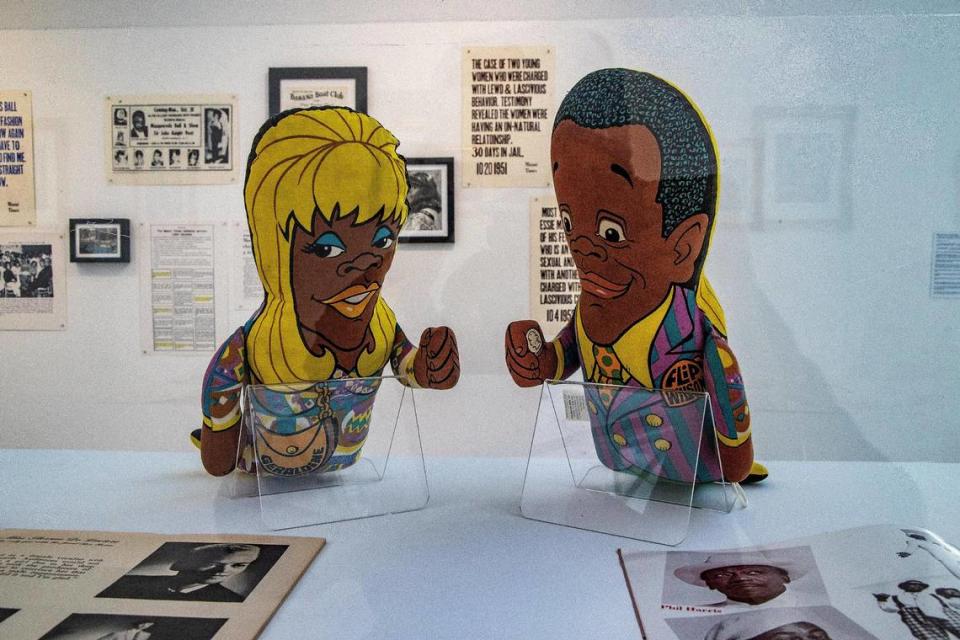

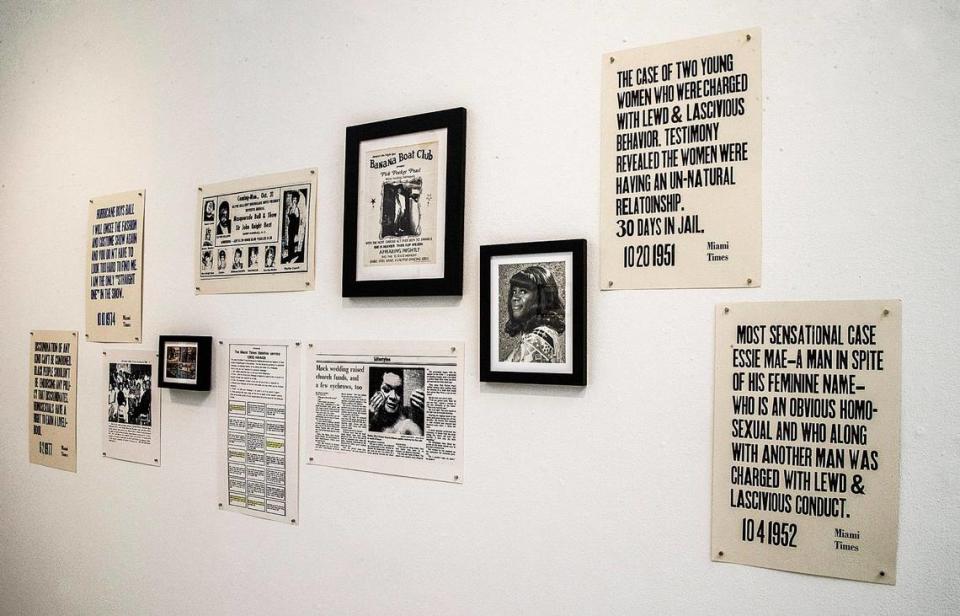

The next section explores Miami’s often forgotten queer Black history.

On one wall are collage artworks made by Kendrick Daye featuring big names in Black entertainment who visited or lived in Miami. Josephine Baker, the famed Black American dancer who was bisexual, is credited with desegregating the Copa City Club in Miami Beach.

On the opposite wall are archived advertisements and photos of a drag masquerade ball in Miami hosted by legendary club promoter Clyde Killens. Another framed poster invites folks to see the fabulous Pick Pocket Pearl “with the most curious act ever been to Jamaica.”

One poster shows a quote from a 1977 editorial from the Miami Times, a newspaper that covered Miami’s Black community, that defended a law that protected gay people from job discrimination. The newspaper printed: “Discrimination of any kind can’t be condoned. Black people shouldn’t be endorsing any policy that discriminates. Homosexuals have a right to earn a livelihood.”

And then there’s a full Miami Herald story from 1983 with the headline: “Mock wedding raised church funds, and a few eyebrows, too.” The photo shows Pick Pocket Pearl herself putting on makeup to play the maid of honor. The group of drag queens attracted a crowd of 500 people to fundraise for St. Peter’s African Orthodox Church.

“Who gives this bride away?” one queen said during the ceremony.

“I do,” another responded.

“I don’t blame you, honey.”

Remembering the repast

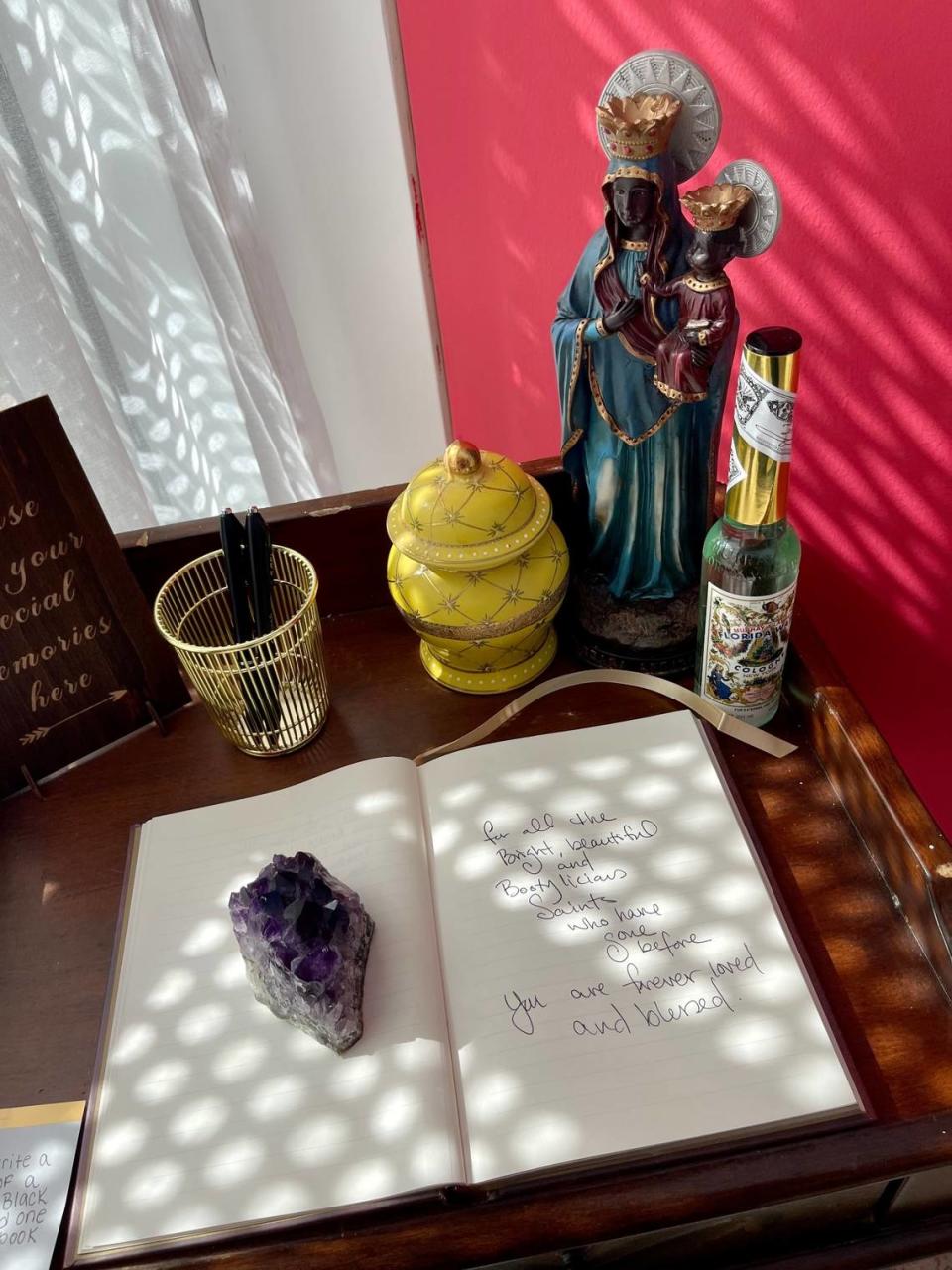

The show ends with a somber, yet celebratory section called “The Repast,” which is where family and friends gather after a burial to tell stories about the deceased, Green said.

The section, which is meant to be a space for people to mourn and remember loved ones, is an artwork installation in its own right by multimedia artist Loni Johnson. A traditional altar space is draped in gold cloth and stacked with photos, jewelry, Florida water and seashells. White candles and cups filled with water are arranged on the ground. A statue of Yoruba goddess Yemaya sits in the corner. A book and pens sit on a desk for people to leave messages.

On the walls are images of Black queer Miamians who have died, like Marion “Flossie” Sheffield, a transgender woman who was killed in Overtown in the ‘50s. Empty picture frames also hang on the walls to represent people whose names are unknown.

There were a lot of tears on opening night, Green said. Folks who were interviewed for the project spoke about how happy they felt to be seen. One woman approached Green and told her about when her oldest son came out of the closet to her. She didn’t take it well at first, but accepts him now. Then her second son came out. Now, she told Green, she can’t wait to bring them to the exhibition to see themselves represented.

“This work is for Black queer folks, period,” Green said. “It is love, right? This is a loving space.”

One person wrote this anonymous message in the repast book:

“For all the bright, beautiful and bootylicious saints who have gone before. You are forever loved and blessed.”

“Give Them Their Flowers: An Exhibit of Black LGBTQ+ Miami History”

Where: Little Haiti Cultural Center Art Gallery, 212 NE 59 Terrace, Miami

When: On view until April 23

Info: Free and open to the public. https://www.blackmiamidade.com/givethemtheirflowers

This story was produced with financial support from The Pérez Family Foundation, in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies