We’re Still Wrestling With What Prince Taught Us About Sex

Has there ever been any musician more famously obsessed with sex than Prince? I don’t mean off-stage. I mean right there in the spotlight, in the grooves of the album, night after night onstage, recording after recording, in his lyrics, his moves, his costumes? We’re speaking, after all, of an artist whose third album showed him attired in an elaborate open jacket, a kerchief, and a banana hammock. That album was called Dirty Mind.

From early until late, the obsession was there in his music, and never mind the lyrics, the song titles alone told the story. Dig if you will this abbreviated list: “Kamasutra Overture,” “Pussy Control,” “Love and Sex,” “Horny Toad,” “Feel U Up,” “Vagina,” “Head,” “Do Me, Baby,” “Sex Shooter,” “Electric Intercourse,” “Wonderful Ass,” “We Can Fuck,” “Erotic City,” “Breakfast Can Wait,” “Cream,” “Sexmesexmenot,” “Orgasm,” “Jack U Off,” and “Soft and Wet.”

But if it’s easy to figure out what was on Prince’s mind, his effect on his audience was more complicated. Women loved him, and he loved them. As for men, heterosexual men anyway, he seems to have disarmed and threatened in equal measure. It’s interesting how many male writers get around, sooner than later, to visually comparing Prince and Bambi, which is suspiciously infantilizing, or at least an attempt to make Prince a little less threatening. For gay men, Prince seems to have been less threatening but no less mystifying.

Taylor Swift Follows Prince: The Artist Who Tamed the Corporate Giant

Two books forthcoming in November, both by men, take Prince as their subject: Hilton Als’ My Pinup: A Paean to Prince and Nick Hornby’s Dickens and Prince. These two short, unclassifiable book-length essays could hardly be more dissimilar, but they are united in their estimation of Prince as artist and changemaker, deepening and enhancing our appreciation on almost every page.

Their different approaches are obvious in their titles. Als writes about Prince and his music from the perspective of a gay man who was attracted both to the man and his music. Hornby as a straight man writes about Prince not as a sexual creature, though he has smart things to say about Prince’s sexuality, but as an inspiration.

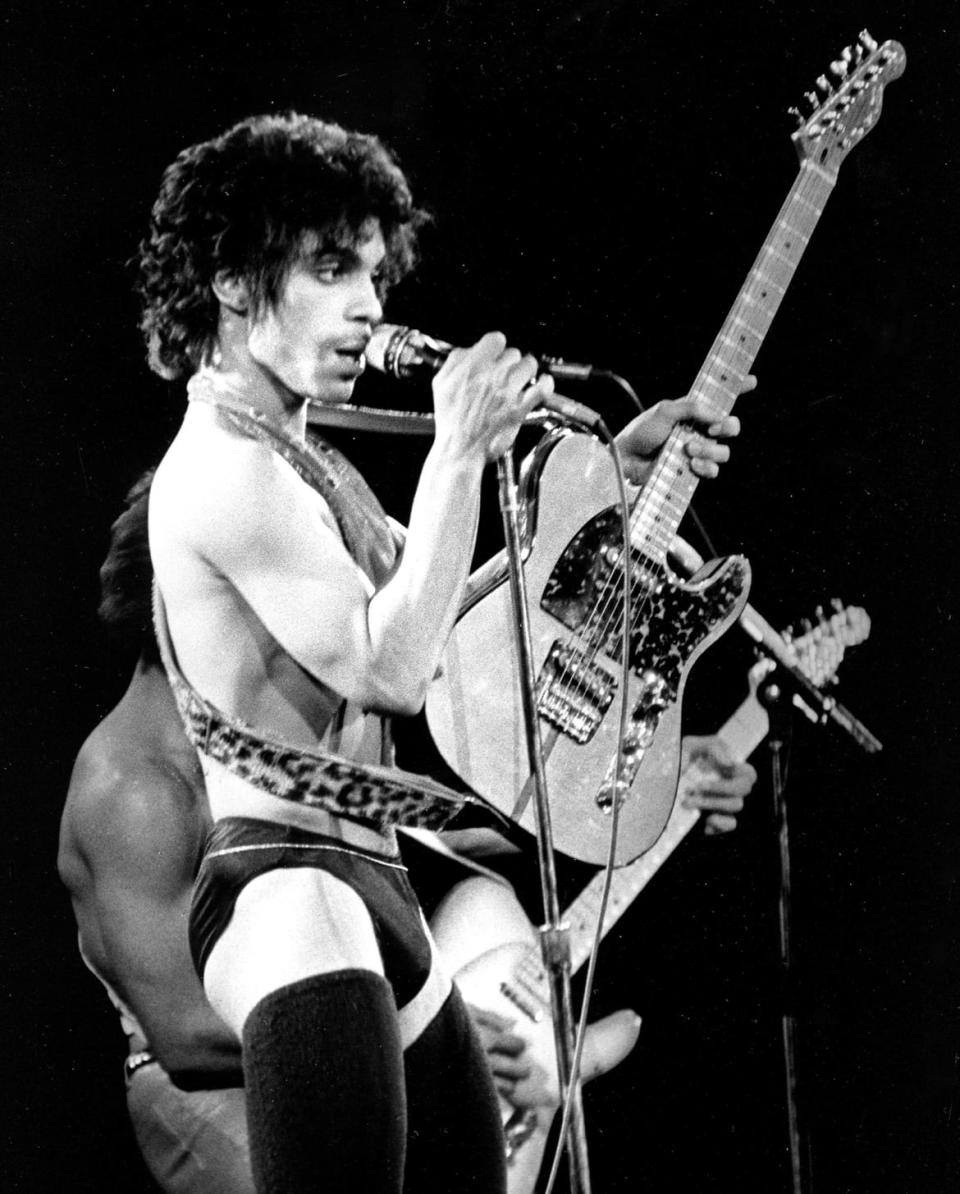

Prince performs at Cobo Hall on Dec. 20, 1980, in Detroit, Michigan.

This is where the pairing with Dickens comes in: both were insanely gifted artists who created an insane amount of top-drawer material in roughly the same time span. Dickens was 58 when he died, and Prince was 57. Right from the jump Hornby warns us off the weirdo Kennedy-Lincoln type of comparison. But the similarities are intriguing. Both men emerged in their respective fields almost fully formed as artists, both had their first big hits in their early twenties, and thereafter both worked tirelessly (an understatement in both cases) and with great artistic success right up to their untimely deaths (more untimely in Prince’s case, as Hornby points out, since dying at 58 in the 19th century meant you’d beaten the odds at least by a little).

Hornby and Als might dislike each other’s books. They certainly don’t like the same Prince. Als trashes the period that produced 1999 and “Little Red Corvette” and Purple Rain and even some of Sign ‘O’ the Times as “self-consciously ‘white’ pop” aimed at frat boys. Hornby loves that material and thinks Sign ‘O’ the Times is Prince’s finest album. But no matter, because as both men would surely agree, Prince contains multitudes. Or as Als puts it, “Like a figure in a Platonic dialogue, I had always longed to meet my other half, my Prince half, and then another, and another, just as Prince was always himself, and then another, and then someone else.”

Als’ appreciation for Prince has something possessive about it. He loves the early albums, then takes a break until Lovesexy, feeling betrayed when “what mattered was Prince’s acquisition of a larger audience… not the black queens who lip-synched to ‘Sister’ while voguing near the Hudson River in the clear light of night.” And: “He was like a bride who left me at the altar of difference to embrace the normative. Could my queer heart ever forgive him?”

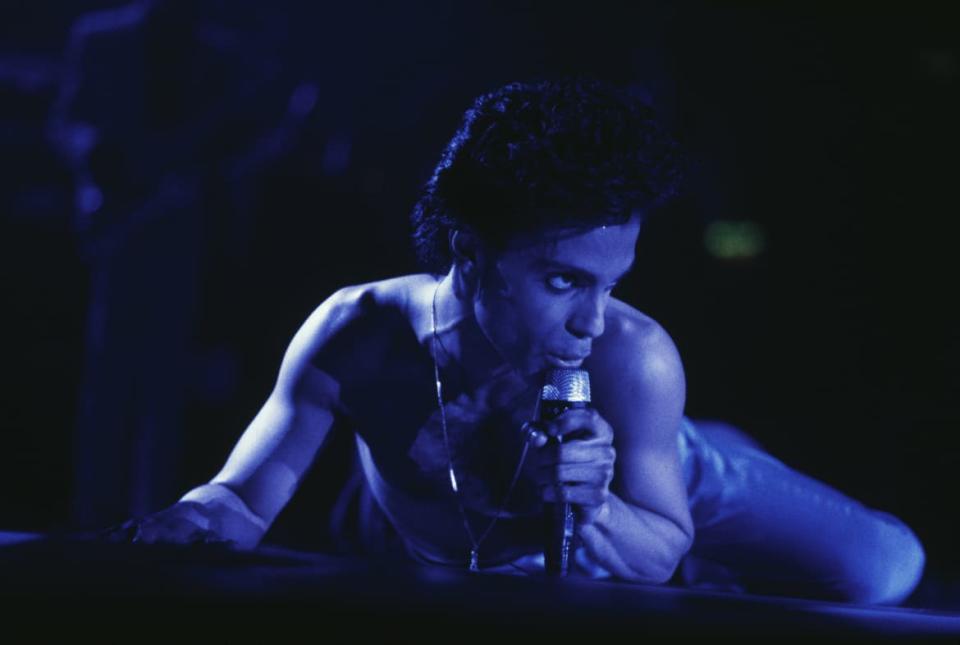

Prince performs on stage on the Hit N Run-Parade Tour at Wembley Arena, London, in August 1986.

In the end, there is Prince and there is a lover, and for Als the two merge: “I inched closer as he danced to you, Prince. But he already was you, Prince, in my mind. He had the same coloring, and the same loneliness I wanted to fill with my admiration. I couldn’t love him enough. We were colored boys together. There is not enough of that in the world, Prince—but you know that.”

There is nothing so personal in Dickens and Prince, which is not to say that Hornby’s book isn’t heartfelt. His love for the work, for the sheer unbelievably prodigal output of both artists, is intense. And when he does write about Prince and sexuality, he is almost jarringly illuminating, particularly when he wrestles with Prince as shapeshifting sexual avatar: “He was that relatively rare creature, the androgynous heterosexual.”

As early as the ’80s, Hornby writes, Prince was showing us that gender is fluid, that we all live on a sexual spectrum. “Prince’s sexuality came from the future… And yet here we are, in the future, and a lot of people finally do understand, or are beginning to.” Ultimately, “Prince was a heterosexual man who loved women, but he was like a member of the sexual civil service: his personal views were his own, and they didn’t affect his ability to do what he saw as his job… which was to embody sex, onstage and on record, and whatever sex was to you was fine by him.”

Prince performs on stage on the Hit N Run-Parade Tour, Wembley Arena, London, August 1986.

Hornby is the more consistently funny writer, which is to say that he more readily and more frequently acknowledges the humor in Prince’s outrageousness. But it is Als who records the funniest moment, which is worth repeating at length. It occurs when he visits Prince before a show as a reporter. Prince does not say much of interest in the initial backstage interview, but the two men seemed to bond, because before he goes onstage, Prince invites Als to collaborate on a book and then asks him to come back after the show. “There’s some people I’d like you to meet.”

So Als goes backstage after the show, not quite sure why he is being asked back. “When I was asked in, I found Prince sitting on the sofa with funk legend Larry Graham, and Graham’s wife. They were all holding Bibles. They wanted to talk to me about Jehovah, and what it meant to be a Jehovah’s Witness.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies