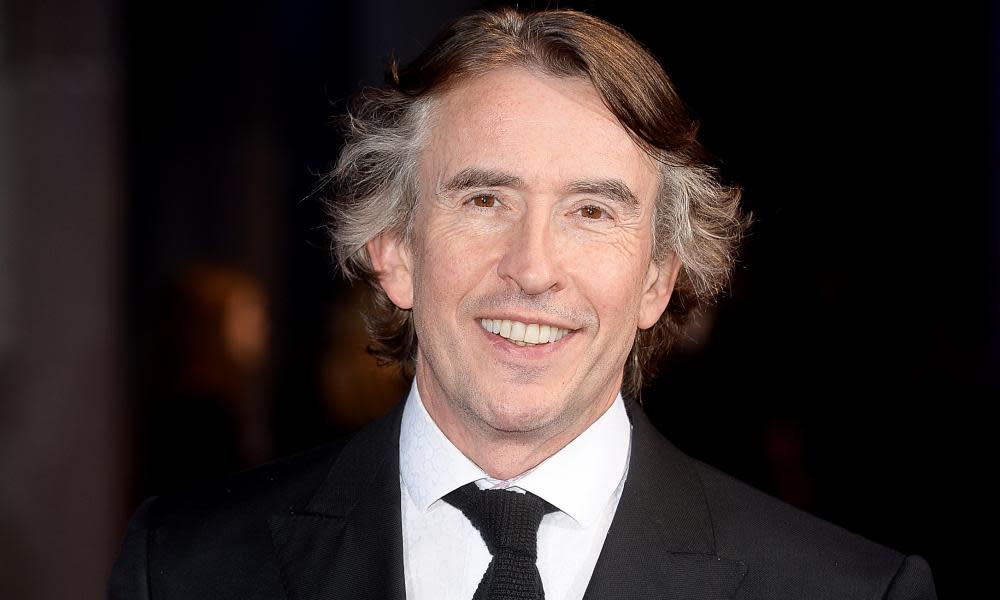

Steve Coogan sets his sights on the life of a fugitive king

Steve Coogan, fresh from the story of the discovery of Richard III’s bones in The Lost King, is now to tackle the life of King Charles, with the help of Princess Diana’s brother, Charles Spencer, and his longtime writing collaborator, screenwriter Jeff Pope. The monarch in question is not, however, our current king, but one of his predecessors, Charles II.

“Rather than a sequel to The Lost King, I suppose you could call it a prequel to where we are now, with King Charles III,” the actor told the Observer.

Coogan is currently to be seen in cinemas as the husband of Philippa Langley, the woman whose determination led to the extraordinary uncovering of the remains of Richard III in a Leicester car park. But he is already researching the story of Charles II’s escape and flight from Oliver Cromwell’s troops in 1651.

He and Pope are about to track the path of the fugitive king, as they put together a screenplay. The new project, in which Coogan will be cast in a supporting role, was inspired by the 2017 book To Catch a King, written by Spencer, Viscount Althorp.

“I’ve had a Zoom meeting with Charles, which went well,” said Coogan, who, with Pope, secured the rights to the book this spring. “It is going to be about a pompous young king who is humbled by contact with ordinary people.”

It is a story which Pope believes will have added resonance after the upheaval of the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. “It is about the sort of up-turning of things that should have resonance,” he said. “After the execution of Charles I no one in society knew where they were.”

Their film will be “a kind of reverse Pygmalion story”, according to Coogan, in which someone privileged learns how to behave in a different way, including having to hide inside that famous oak tree as Cromwell’s troops pass by. “I am not a monarchist, so I suppose the message that appeals to me is that wisdom and integrity are not conferred by wealth. Those kind of virtues are classless ones.”

Both Pope and Coogan have prolific solo careers. Coogan, aside from playing Alan Partridge, the Norwich-based DJ and chatshow presenter with a life of his own, has appeared in a string of Hollywood films and television dramas, while Pope is behind many of the most highly acclaimed real-life television dramas of the last decade, including The Widower, A Confession and the up-coming Stephen Graham drama The Walk-In.

But the pair have a lengthy track record together, with hits such as Philomena, the Stephen Frears film they co-wrote, Laurel and Hardy biopic Stan & Ollie and a controversial new series, The Reckoning, which stars Coogan in the role of Jimmy Savile. Written by Neil McKay, but produced by Pope, it comes to BBC One soon.

“Charles II will be our sixth or seventh project together and we’ve more lined-up,” said Coogan, who describes their partnership as like “meat and potatoes”. Perhaps they also dovetail like Laurel and Hardy, the comedy duo at the centre of Pope’s admired screenplay, in which Coogan played comedian Stan Laurel.“We come from a similar background,” said Coogan. “I like to think Jeff is the Essex version of me. We are people who have grown up having breakfast, dinner and tea, and are less rarefied than most writers. There’s a creative tension between us, so we have robust arguments, but also a kind of feeling for moral justice.”

Both are grammar school boys from what Pope describes as “aspirational backgrounds” and they share a productive resentment of the entitled classes. They also bond over a conviction that you don’t have to give the public “garbage” to entertain them, Coogan adds: “Although we are certainly populists, we believe there is something between The Bodyguard and I May Destroy You.” There’s a chippiness that drives their choice of subject matter, Coogan admits: “We like stories about the little person against the Behemoth. We get incensed and that’s what drove us to write The Lost King.”

Some of the archaeologists who worked on the Richard III dig have been unhappy to be cast as the villains of their story, but Pope and Coogan stand by their version.

They never go in with an agenda, Pope claims, but Coogan confesses to a liking for embarrassing the comfortable professionals in any narrative. “We put our ideas through the ringer before we decide on one,” he said. “And for me there is a real joy in the research side of it too. That’s a way of educating myself.”

The actor has also been criticised for portraying Savile in The Reckoning so soon after the crimes were revealed. It is something that rankles with Coogan. He suspects there is “a blanket view” that he should not take on such subjects. Why were the actors David Tennant and Stephen Merchant not criticised for playing the parts of horrific serial killers such as Dennis Nilsen and Stephen Port, he wonders, although Pope does acknowledge an especially troubling element in Savile’s story.

“I’ve made a lot of stuff about serious crimes, whether about Ian Brady or Fred West, yet this is more challenging. It was all in plain sight, so the question is, ‘Why did we let these things happen?’”

Coogan wants to look at the way Savile’s deeds affected those around him, rather than to explore the psyche of the offender himself. “You do have to walk across the hot coals to do something as difficult as this. We may want to turn away, but that’s not always a healthy thing.”

He hopes the show’s audience will confront the fairly recent tolerance in society for the idea of sex with underage girls. Savile was like a stage magician, he suggests, who “discombobulated” people around him to distract them. “I know there are different ways to play him and that if you look at the whole person, there is a danger you seem to be giving him some respect. But then if you caricature him instead, and make him into a pantomime figure, that isn’t right either.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies