Steelhead trout are struggling on California’s Central Coast. How scientists want to save them

It’s a fickle fish — one that evades even the most experienced anglers and darts for cover when curious passersby try to spot its freckled body against the backdrop of a gravel-lined stream.

Despite capturing the attention of many local scientists and conservationists, California’s Central Coast steelhead trout remain listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act, according to the latest review of the species released in May by the National Marine Fisheries Service, an arm of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The population segment on the south-central California coast reviewed by the federal agency, which has a range stretching from the Pajaro River in Monterey Bay to Arroyo Grande Creek, was first listed as threatened in 1997. It hasn’t appeared to improve since then.

A listing as threatened means the population is close to becoming endangered or at risk of extinction.

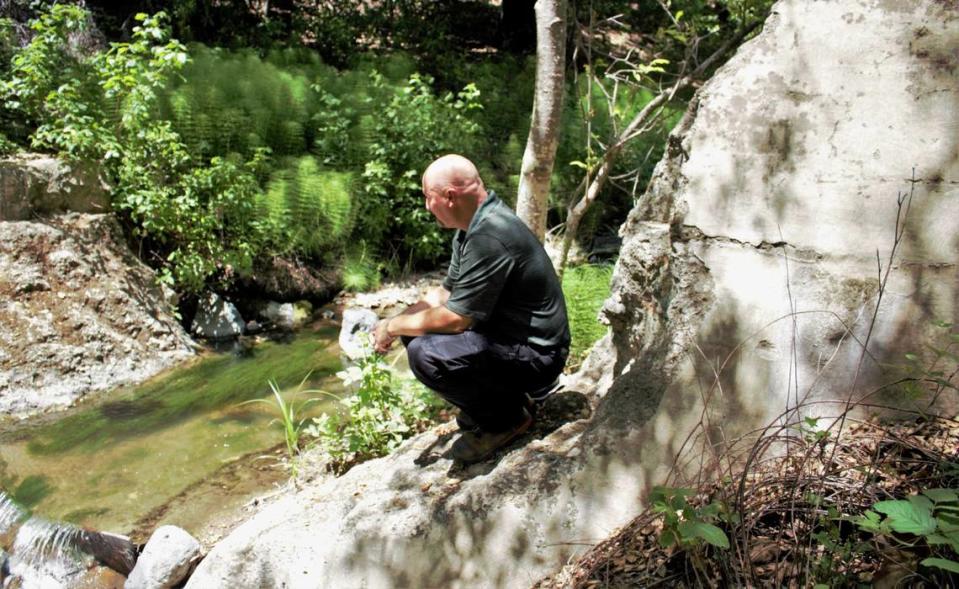

Devastated by drought and blocked migration pathways through their habitat, steelhead in San Luis Obispo County are struggling to survive in the waters where they were once abundant.

“These fish are canaries in the coal mine,” said Freddy Otte, biologist for the city of San Luis Obispo. “If they’re gone, something is wrong; our creeks aren’t healthy.”

The plight of the steelhead has motivated conservation and restoration efforts across the county in an attempt to save the species.

Teams of scientists have united to pool their data and countless hours toward studying the steelhead and restoring its San Luis Obispo County habitat.

With the proper resources, the work could benefit not only steelhead, but also entire ecosystems impacted by climate change and human interference.

“These are our lands and waters that if we don’t take care of them, and we lose our steelhead, that’s absolutely on us,” said Don Chartrand, executive director of Creek Lands Conservation, a local nonprofit organization that works on conservation plans and restoration projects.

“If the steelhead don’t exist, our watersheds are going to unravel even more,” added Steph Wald, watersheds projects manager at Creek Lands Conservation.

Trout once filled SLO County creeks

Steelhead trout are considered an indicator species, scientists say.

If you see lots of them swimming in a stream, that likely means the water quality there is quite good. An absence of the fish could mean the water is polluted, too warm or lacks the proper nutrients for animals to survive.

The steelhead starts its life in freshwater creeks and streams.

Some of the fish, known as steelhead, then migrate to the ocean to grow big before swimming back to freshwater to lay eggs and start a new generation. Fish that never swim out to sea are called rainbow trout.

Collectively, the fish are known by the species name Oncorhynchus mykiss despite genetic differences between the two.

Through the Great Depression, San Luis Obispo County creeks brimmed with the fish, according to historical accounts.

“If one had nothing else for dinner, there were always the fish in San Luis Obispo Creek,” Rose McKeen writes in a 1988 book about historical San Luis Obispo. “During those disastrous years, the creek literally fed many people, just as it had once fed the mission padres and the Chumash Indians.”

Pollution, dams, levees and severe drought have since left the creeks with little to no steelhead.

This year, Otte said he hasn’t seen a single steelhead in San Luis Obispo Creek. Others have seen small juveniles, but there’s a noticeable absence of the large adult steelhead.

“Historically, there were thousands of fish in our streams,” said Don Baldwin, an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. “Today, we’re lucky to see any.”

Decline of steelhead due to drought, migration barriers

The National Marine Fisheries Service’s five-year review of the species released in May attributes the lack of steelhead to two main factors: devastating drought worsened by climate change and blockages in creeks that impede migration paths.

Without enough water in the streams, steelhead simply cannot survive.

“The big story is the prolonged drought during this five-year review period,” which caused local streams to shrivel to trickles, said Mark Capelli, the local steelhead recovery coordinator for the National Marine Fisheries Service. “On top of that, we had numerous wildfires in the various watersheds and then there was a deterioration in ocean conditions, which were not conducive to the rearing of adult steelhead.”

Wildfires in the Big Sur area filled streams with charred debris and ash — and record-high ocean temperatures from 2013 to 2019 likely caused many of the adult steelhead to die, according to the National Marine Fisheries Service’s report.

Human-made barriers in streams, such as dams, have also likely hurt the population by impeding where the fish can migrate to lay eggs, the report said.

Lack of comprehensive monitoring impedes species assessment

Figuring out how many steelhead are swimming up and down the Central Coast’s streams is a difficult task because of a severe lack of funding and staffing.

“The lack of comprehensive monitoring has ... limited the ability to fully assess the status” of the species, the National Marine Fisheries Service’s population review said.

The state has funded coastal monitoring programs for steelhead and salmon in areas north of San Luis Obispo County, such as the Carmel and Big Sur rivers.

South of that, however, there isn’t a dedicated funding source for counting the fish locally, Baldwin said.

Any monitoring efforts conducted in San Luis Obispo County streams are conducted through a patchwork of self-funded efforts by Fish and Wildlife, local cities, nonprofit and non-governmental organizations.

“Funding and staffing is the biggest challenge,” Baldwin said. “And then, even once you have the staffing, landowner access can be a challenge. A lot of our creeks are on private property — anywhere from large ranch lands to small urban subdivisions —and it’s difficult to get full access.”

A bill introduced by California State Assembly member Steve Bennet, D-Oxnard, would stabilize funding toward coastal monitoring by Fish and Wildlife by establishing a dedicated fund to support the programs.

Assembly Bill 809 has yet to pass through the Assembly for a vote by the California State Senate.

Plus, it’s difficult to monitor a species that tends to avoid human interaction, Baldwin noted.

“Steelhead are very difficult to monitor because they are so elusive,” he said.

“We’re chasing ghosts. We never see them,” Baldwin said. “They can come in one day, spawn overnight and head back to the ocean.”

Restoration projects could help boost steelhead population

Steelhead restoration efforts over the past few decades across San Luis Obispo County have attempted to make the area more habitable for the important fish.

The groups conducting this work hope that by helping to repair habitat for the steelhead, the entire watersheds will benefit and become more resilient to climate change impacts.

For example, an old city water system dam on San Luis Obispo Creek along Highway 101 on the Cuesta Grade was knocked down about two decades ago to allow fish to migrate through there.

The city of San Luis Obispo also removed a culvert on Coon Creek at Pecho Valley Road — an access road to Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant — in 2004.

A 1930s-era stream gauge on Arroyo Grande Creek near the intersection of West Branch Street and Highway 101 is slated to be modified so steelhead can jump over it and continue to migrate to better habitat upstream.

That project, primarily carried out by Creek Lands Conservation, is a collaboration between the county, city of Arroyo Grande, Lucia Mar Unified School District, California Conservation Corps and private landowners.

Other restoration efforts around the county include a new San Luis Obispo Creek resiliency and rewilding plan funded by the Harold J. Miossi Charitable Trust; predator removal in areas such as Chorro Creek, which feeds into the Morro Bay estuary, and rehabilitation of the Villa Creek estuary north of Cayucos.

To combat drought, Creek Lands Conservation is working to design and soon implement what it calls streamflow enhancement projects.

The process could increase streamflows during abnormally dry periods by strategically releasing water stored in tanks or reservoirs into drought-thirsty streams.

Preventing steelhead from becoming endangered takes more than just monitoring the population and working to fix up habitats, Chartrand said.

Scientists can study the steelhead, release reports and perhaps implement successful restoration projects, he said. But all of that work means nothing if the public doesn’t know about it or doesn’t care about it, he added.

“We need to change that legacy of decision making that costs us our natural heritage,” he said. “We just can’t afford (not to do) it.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies