Stanley, an Idaho mountain mecca, is changing. Can its little-town character survive?

Despite rapid population growth, there remain places in Idaho that are rural. Towns with few people and big mountains; small human footprints and abundant wildlife.

Many such places have long since ceased to be inconspicuous, drawing attention and money from the recreation- and seclusion-minded. To some, the pattern has been devolution: special places gobbled up by a wealthy few looking to buy their own piece of paradise.

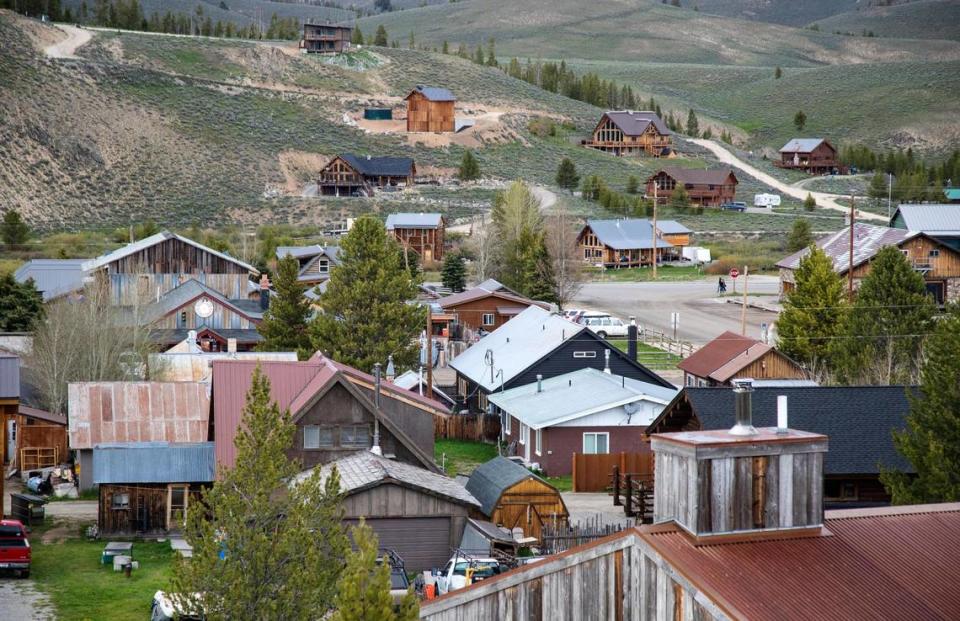

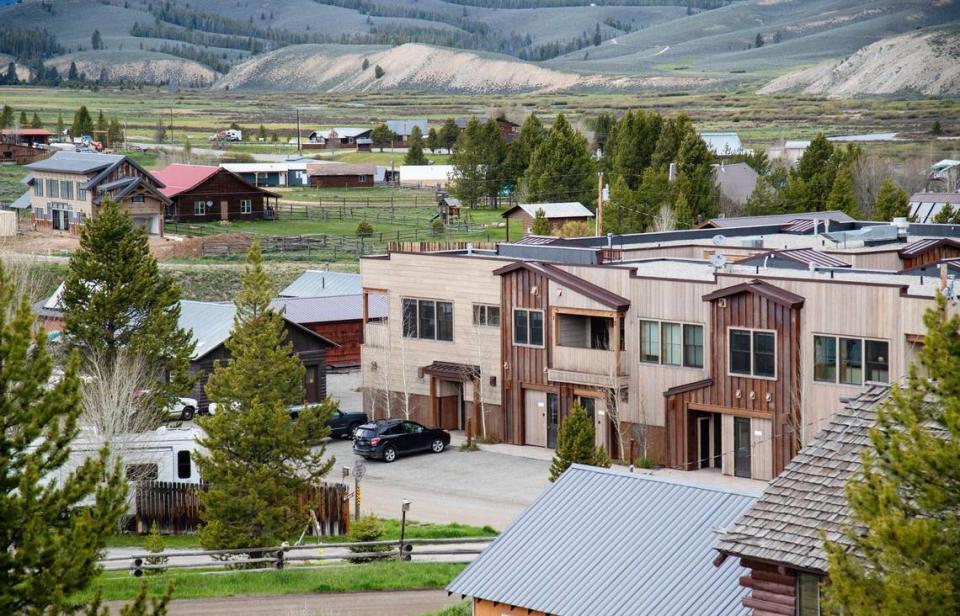

One of the state’s most popular mountain destinations faces a somewhat different problem. Surrounded by hundreds of miles of public land, Stanley is fenced in, unable to expand outwards and with a city code that attempts to limit the visual footprint new homes can have.

But recent building has skirted the town’s efforts to keep Stanley looking rustic. And while encircling public land has kept the mountain village from advancing farther into the Sawtooth Valley, it has caused its own problems, as a shortage of affordable housing threatens the local businesses that keep the town up and running.

People in Stanley are ‘a little bit different’

Aside from the two highways that form a T just east of town, many of Stanley’s roads are unpaved. The town has no high school and no police officers — a contract with the Custer County Sheriff’s Office supplies the law enforcement.

The school has two teachers and offers from kindergarten to eighth grade, with about 18 students. For high school, teenagers must go to Challis, a town that is an hour’s drive away.

The school does not have a bus driver, according to Amy Klingler, the town’s physician assistant, so her child chose to take classes online.

There’s also no full-time doctor. Klingler runs the clinic on Niece Avenue, and a doctor visits once a month.

In the winter, avalanches can shutter both highways, blocking access to the remote village for days on end. The electrical grid runs south from Challis, and power to the town once was cut off for three days when the temperature hovered around 40 degrees below zero.

But while the town lacks certain amenities, it continues to attract residents committed to life close to nature, to public land, and to the magnificent crags that serve as the valley’s backdrop.

It takes a certain type of person to live there.

Maryellen Easom came to Stanley from Oregon in the early ‘80s for a backpacking trip with a friend. While in town doing laundry, she ran into a woman who ran a ski-hut business who hired Easom on the spot to work at her lodge.

Over the next several years, Easom worked odd jobs, including as a cook, scooping ice cream and shoveling snow — all to stay in the Sawtooth Valley. She eventually became the head teacher in Stanley, and worked at the school for 30 years.

“People who end up coming to an area that maybe isn’t really easy to live in are a little bit different,” she said, “and maybe think more creatively. I just enjoyed the people that I met here.”

‘Housing is a real issue’

Much of the efforts would-be residents must devote their creativity to is finding a place to live.

The small village faces a major housing crisis. Around 20% of the town’s workforce is homeless, the mayor said, living out of tents or camper vans while working in bustling restaurants and outdoor shops in the summer.

And as a resort town, many of the larger homes in the area are second homes, with owners only in town for parts of the year.

“All these places that are tourism-oriented towns have housing problems, but here most of the people who work here have difficulty buying a house or even buying a lot that they can build a house on, because the real estate prices are so high and since there’s such a scarcity of private land within the city limits,” Botti said.

Easom said she’s lived in 17 places in the Sawtooth Valley over the last 40 years. She and her husband — a river guide — would often find a place to live for the summer that wasn’t winterized, meaning they’d have to leave when the seasons changed.

For 27 years, the Easoms were the caretakers of a home, living there in the fall, winter and spring and moving out in the summer, when the owners came for the season. In 1990, they bought property outside of Stanley and put up a yurt — with no running water other than a pump, and no electricity — and camped there in the hottest months.

“Housing is a real issue,” Easom said. “In the summer it’s really hard, because businesses can’t get workers, because they have nowhere to live.”

Some restaurants and other businesses have to stay closed multiple days per week due to worker shortages, she said.

Other businesses have developed ways to provide housing for employees.

Tim Cron, the co-owner of Stanley Baking Co. and the Sawtooth Hotel, said he has space for around 20 of the employees at his businesses to live. But another 15 or 20 employees still need to figure out their own housing.

At Redfish Lake Lodge, a few miles south of Stanley, the employees are also mostly housed on site. The lodge sits in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, a large and rugged forest with over 300 alpine lakes and many peaks over 10,000 feet.

For those workers who plan to solve their housing woes by camping, problems remain.

Easom noted that, even for those employees who camp, Forest Service regulations put in place during the pandemic have made that prospect close to impossible. Camping limits in the recreation area are 10 total days within a 30-day period, after which a person must move at least 30 miles away.

That distance “would mean you’d have to move out of the valley, virtually,” Easom said.

A major aspect of the housing troubles is the inability to grow. Surrounded by public land, Stanley cannot expand, only infill, Botti said. Around 15% of the town property is still vacant — mostly commercial — land that will likely one day be developed. But there remains a housing supply issue.

“Private lots to be developed for houses are becoming pretty scarce,” Botti said.

One potential solution the town has envisioned would be to build workforce housing on city property. North of town, the federal government ceded 4 acres to Stanley to build housing on when the Boulder and White Clouds wilderness areas were created in 2015 and which adjoins the original recreation area. The city is working on a plan to do that, but concerns remain about the expense of building it, as well as how to maintain revenue at the site when demand for apartments would mostly occur only in the summer months.

“That’s a question we have not resolved yet,” he said.

‘Rustic and Western’

In a town of around 100 people, population counts can fluctuate wildly.

In 2010, Stanley’s population was 63, according to the U.S. Census. In 2020, it rose to 116. Botti is doubtful about both numbers.

“It depends on when you count, because of the wild fluctuation in the population here,” he told the Idaho Statesman. “If you count in the middle of February, you wouldn’t get 116 people. If you count in the middle of the summer, you can get three times as many people.”

Regardless, it’s growing, the mayor said. At least 15 new homes have gone up in the last decade.

As new homes are built, locals are also concerned that some new residents are not committed to maintaining the character of the town.

Regulations on the recreation area stipulate that building should be in line with historic buildings, and Stanley’s own city code includes a provision for buildings to be “rustic and Western.”

The town’s history dates back to the 19th century, when fur trappers and later miners made their way into the Sawtooth Valley, and a town was built to supply their wares, according to Megan Nelson, the Stanley Museum’s docent.

Before then, bands of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes lived in the Sawtooth area and were forcibly removed, said Daniel Stone, a member of the tribe, at a conference on the Sawtooths hosted by the Andrus Center for Public Policy at Boise State University.

After mining, ranching followed, and then recreation, and COVID-19 has accelerated a tourism boom: In 2020, the city’s local option tax, which allows local municipalities in Idaho to raise their own taxes, brought in 40% more in revenue. The following year, it increased another 60% over that, Botti said. Around 70% of those revenues come during the summer season.

Despite the town’s history and efforts to maintain it, new developments have been able to meet the letter of the code while still building modern-looking homes. While contemporary, large homes are common to the south in Sun Valley, some locals don’t want to see that kind of development in the Sawtooth Valley.

“It just doesn’t work here,” Easom said. “Up and down the valley there have been a number of houses … . Where there used to be log cabins, now there are megamansions.”

The City Council recently passed an ordinance to strengthen the zoning code to try to ensure that the rustic requirements are more defined, said Cron, who is also a member of the City Council.

“The trend is that the new building is high-dollar vacation homes that sit vacant most of the year,” he said.

How cold does it get?

To say that temperatures in Stanley can get cold might not do justice to the climate. The town is frequently one of the coldest places in the lower 48 states in summer. Stanley has an average of 293 days per year when the temperature drops below freezing, said Korri Anderson, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Boise. Surrounded by steep peaks, that cold air drains into the valley overnight, where it settles.

The coldest recorded temperature, in December 1983, was minus-54 degrees. In July, the warmest month of the year, temperatures drop below freezing on nearly a third of the month’s days, Anderson added.

Here’s another benchmark: In the winter, the school shuts down for the day when the temperature drops to colder than 30 below zero, Easom said. In any given year, that could happen up to five or six times.

When she started teaching, the standard was 40 below, and Easom — who also became an EMT — went to the school board to explain how skin can freeze in minutes at 40 below, and that it takes slightly longer at 30 below.

“I went to the school board and said, you know, don’t you think we ought to give the kids out there waiting for the bus that margin of error?” she said.

To get their cars to start, people have to use oil-pan or engine-block heaters, Easom said. Or they might try other creative solutions.

“One fellow I know used to take a blowtorch out and put it under his truck,” she said.

Botti said that the cold weather can make “very strange things happen.” One resident told him that one day he came out to start his car, and the door handle “came right off and shattered” when he tried to open it.

Longtime residents, like Botti, come to enjoy the cold, and to appreciate it. The mayor said that when it’s really freezing, there’s often little wind, and a sunny day can be “comfortable.”

“Most people love this place in the summer, it’s just like a Shangri-La — it’s just so beautiful here,” Botti said. “A lot of people have moved to Stanley because they come up in the summer and they just say, ‘I’m gonna buy a house here, it’s a great place.’ And then it’s 35 below zero, long, cold, dark winters, and not so appealing, and so they don’t stay.”

‘Would I want to be anywhere else?’

Stanley is nearly 60 miles from health centers in two directions: north, to Challis, and south, to Ketchum.

In town at the Salmon River Clinic, there’s a physician assistant and a front office manager. This year is the second that there’s been a full-time nurse on staff. A doctor, based in Hailey, drives up to see patients once a month. And a courier, who brings mail from Twin Falls, also picks up prescriptions at a pharmacy in Ketchum each weekday.

The town’s isolation means that strong relationships are vital to its functioning.

“We’ll call one of the Idaho Transportation Department drivers to drive the snowplow in front of the ambulance if we need it,” said Klingler, the physician assistant. If necessary, an ambulance will leave Stanley with a patient, while another, more well-equipped one will leave Ketchum, and the two will meet on the highway to transfer the patient.

Patients in critical need can also get flown to Boise via helicopter, which Klingler also coordinates, as well as responding to calls as an EMT.

She chose to become a physician assistant over going to medical school specifically because of the job in Stanley — a position that fulfilled a dream of living in a place close to the outdoors and with a tight-knit community, she said.

“There’s that kind of Western independence, but knowing that you have this community to rely on if you need something or something happens, I think is super comforting,” she said.

“I love walking down the street and waving. I love the fact that when I got a new car, people were like, ‘Where’s Amy?’ ” she said. “Nobody knew who I was, because I got a new car.”

In such a small town, there’s a lot of overlap between professional and personal life, and Klingler said medical confidentiality is vital, since she’s apt to see patients at the grocery store, or at a restaurant.

Though not able to do surgery or other procedures, physician assistants can diagnose, treat, prescribe to patients and interpret lab and imaging studies.

When she goes on vacation, Klingler has to coordinate finding a replacement, and if she were to get sick and couldn’t find one, the clinic would have to close. As the only provider, she’s not able to walk down the hall to ask a physician a question about a diagnosis, and persuading a patient to drive an hour to the nearest hospital can sometimes be difficult.

Until the Sawtooth National Recreation Area was founded, Stanley had no health clinic. Employees of the Forest Service would try to provide medical care to residents, Klingler said.

Even with the clinic, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary, the demands are mounting. The summer season, which is getting longer, can have “extreme” demands for local health care providers, not least because many visitors do not understand the town’s ruggedness, and may expect to have a faster medical response than is possible, she said.

“Would I want to do anything else? No,” she said. “Would I want to be anywhere else? No.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies