Spain passes law to bring ‘justice’ to Franco-era victims

Five decades after the death of General Franco, and three years after the Spanish dictator’s remains were finally removed from his hulking mausoleum outside Madrid, the country’s senate has approved legislation intended to bring “justice, reparation and dignity” to the victims of the civil war and subsequent dictatorship.

On Wednesday afternoon, the upper house of Spain’s parliament passed the socialist-led government’s Democratic Memory law, with 128 votes in favour, 113 against, and 18 abstentions.

The legislation, which was approved by Spain’s congress in July, contains dozens of measures intended to help “settle Spanish democracy’s debt to its past”.

Related: Old wounds are exposed as Spain finally brings up the bodies of Franco’s victims

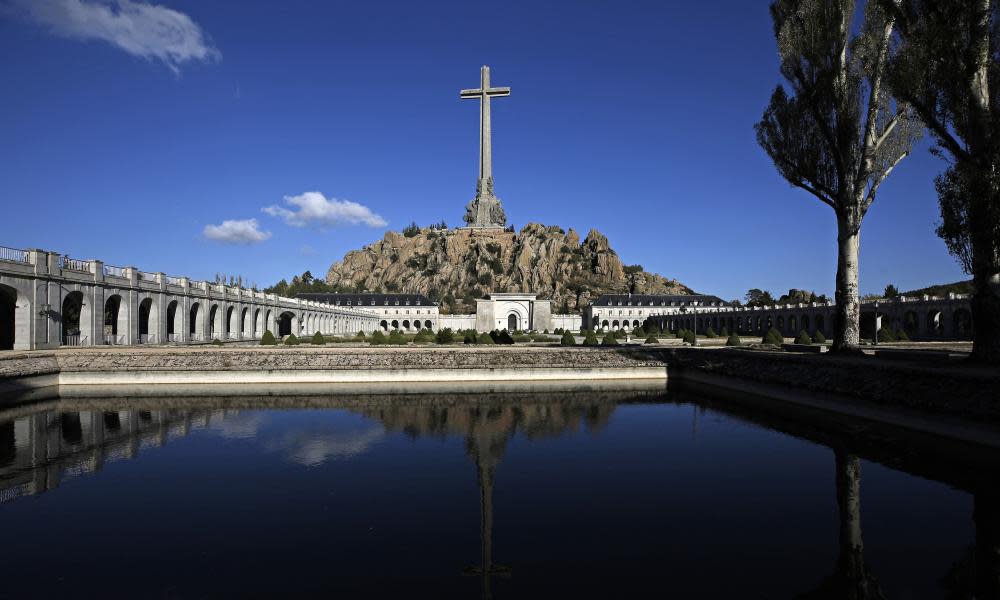

Among them are the creation of a census and a national DNA bank to help locate and identify the remains of the tens of thousands of people who still lie in unmarked graves, a ban on groups that glorify the Franco regime, and a “redefinition” of the Valley of the Fallen, the giant basilica and memorial where Franco lay for 44 years until his exhumation in 2019.

According to the government of Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez, the legislation will help “encourage a shared discussion based on the defence of peace, on pluralism and on broadening human rights and constitutional freedoms”.

In a tweet after the vote, Sánchez said: “We socialists have always worked to strengthen our democracy and today we have taken another step towards justice, reparation and dignity for all the victims.”

The new law builds on 2007 historical memory legislation introduced under another socialist prime minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, which was resisted by Spain’s conservative People’s party (PP). Many on the Spanish right have opposed legislative efforts to revisit the past, saying they risk undermining the 1977 amnesty law and the so-called Pact of Forgetting that helped to usher Spain back to democracy after Franco’s death.

Born in 1892 in Ferrol, Galicia, Francisco Franco Bahamonde was a Spanish general and politician who ruled over Spain as head of state and dictator under the title Caudillo between 1939 and 1975.

He and other officers led a military insurrection against the Spanish democratic government in 1936, a move that started a three-year civil war. A staunch Catholic, he viewed the war and ensuing dictatorship as something of a religious crusade against anarchist, leftist and secular tendencies in Spain. His authoritarian rule, along with a profoundly conservative Catholic church, ensured Spain remained virtually isolated from political, industrial and cultural developments in Europe for nearly four decades.

The country returned to democracy in 1977 but his legacy and place in Spanish political history still sparks rancour and passion.

For many years, thousands of people commemorated the anniversary of his 20 November 1975 death in Madrid's central Plaza de Oriente esplanade and at the Valley of the Fallen mausoleum. And although the dictator's popularity has plummeted, the 2019 exhumation of his body has been criticised by Franco's relatives, Spain's three main rightwing parties and some members of the Catholic church for opening old political wounds.

The PP, which is now led by Alberto Nuñez Feijóo, has said it will repeal the law if it wins next year’s general election. The party’s previous leader, Pablo Casado, said the law would serve only to “dig up grudges”, while the PP’s Mariano Rajoy – who was prime minister from 2011 to 2018 – boasted of cutting Spain’s historical memory budget to zero after his administration inherited the 2007 law.

Others, however, argue that the new law does not go far enough. The Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARHM), a human rights group that has spent two decades exhuming mass graves and campaigning for justice for Franco’s victims, says the 1977 amnesty law needs to be repealed and financial amends made to those whose goods and properties were seized by the Franco regime.

The ARHM has also called for a census to be made of all those who benefited economically from Francoism, and for the Roman Catholic church to be investigated and held accountable for backing the 1936 coup that brought Franco to power and for supporting the ensuing dictatorship.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies