‘Why did you murder my father?’ How Liz McGregor confronted a killer

Two days after burying her mother’s ashes in the summer of 2008, Liz McGregor received a devastating phone call. Her 79-year-old father, Robin, was also dead – and his house 75 miles north of Cape Town, where she lived, was now the scene of a murder inquiry. His car, a bronze-coloured Mercedes that had for years been his pride and joy, had been discovered by police a few miles away in a poor neighbourhood with its lights on. A man was arrested as he tried to run away and officers found blood on his clothes. In the house itself there were no fingerprints, because whoever had murdered Robin McGregor had been wearing gloves.

So began a story that brings McGregor face to face with South Africa’s brutal history and the violence it has spawned. Her new book, Unforgiven: Face to Face with My Father’s Killer, is so unflinching that it challenges its readers to look away first: it’s her way of processing the horror, she says. “It changed me fundamentally. When you get such a profound shock, you rethink everything. I’ve always lived my life afraid of what might happen, and when this earthquake happens, at the start you become slightly numb, then you become grief-stricken and terrified and angry, and gradually you become slightly more inured to things.”

At the trial of the man who was charged with her father’s murder, McGregor and her four siblings listened as the gruesome details emerged over many weeks. “I am a journalist,” she writes. “I have covered murder trials in this very court. I have interviewed victims of violence and done my best to enter imaginatively into their experience to properly convey their pain. But none of it prepared me for the horror of sitting in this stuffy courtroom, day after day, while details of the brutality inflicted on someone with whom I was so intimately connected are revealed in torturous detail.”

Her father was a retired publisher and game farmer, the former mayor of a town in the mountains of the Western Cape that was coincidentally called McGregor. He had become a bit of a celebrity in his younger days after publishing a bestselling book exposing the grotesque monopolistic corruption of apartheid, and was rewarded with a place on the Competition Commission in the early days of Nelson Mandela’s presidency.

He had spent 11 August 2008 with his son’s family, who recalled him patiently explaining the US sub-prime crisis to his young grandson. After they left, he ran himself a bath, in which it was his habit to wind down with a book at the end of each day. He was still in the bath when intruders broke in. “Some time between 10pm and midnight he was murdered,” writes McGregor. The blankness of that sentence is where the enduring trauma lies. His body had been found with 27 stab wounds, the fatal one of which was a slash to his neck that severed his carotid artery. Practical to the last, even in his final seconds, he had tried to staunch the bleeding with his pyjamas. As she recounts this particular detail, McGregor starts to quietly weep, impatiently wiping away her tears to carry on talking. Even 14 years on, this always happens, she says.

The forensic facts reveal everything and nothing. Part of the trauma, the reason she has found it so hard to recover, she says, is that her father’s killer still maintains his innocence, and refuses to reveal what really happened, even though he was convicted and imprisoned for 30 years, and all the evidence – including her father’s blood on the clothes he was wearing at his arrest – confirms his guilt. This has prevented the family from understanding how he came to be targeted, why he was so brutally treated in such a prolonged attack, and how many people were involved. He had recently moved to a new house, which he had extensively renovated.

As a farmer, he was used to keeping cash in one safe to pay his workers and guns in another to protect himself and his family. He had ensured his children knew how to protect themselves, but had also drilled into them that one key survival skill was to know when not to put up any resistance. “We can only assume that one of the workmen helping him on the house saw the two safes, and tipped off a local gang, and in his shock and panic he forgot the combinations of the locks,” says McGregor. The safes were wrenched out of the wall and the cash and the guns were taken along with the car.

Robin McGregor was a third-generation immigrant of Scottish extraction whose great-grandfather had abandoned a wife and children to seek his fortune in the South African gold fields. Cecil Thomas, the man convicted of his murder, was a 33-year-old from a Coloured (the term still used for South Africa’s mixed-race population) family that also probably had roots in 19th-century Scotland. In her desperation to understand, McGregor travelled to the Western Cape town of Saron, where Thomas grew up, the youngest of 10 children with a loving mother and grandmother but a largely absent and fitfully violent father who died when he was 14. Spooked by the small, isolated settlement that had been founded by German missionaries as a refuge for slaves, she motored on the few miles to Tulbagh, where her father was murdered. “I take out my tourist maps, hoping to see the town anew,” she writes, “but all I see is our country’s painful history writ large.”

The main street of Tulbagh, she discovers, was named after a Dutch governor who, in the 17th century, brought his countrymen out to colonise an idyllic wooded valley that he recognised as “eminently suitable for agriculture”, wiping out or enslaving the original inhabitants in the process. Parallel to that street is one named in honour of the Boer leader who led the Great Trek out of the cape in the 1830s in protest against British rule and the emancipation of slaves.

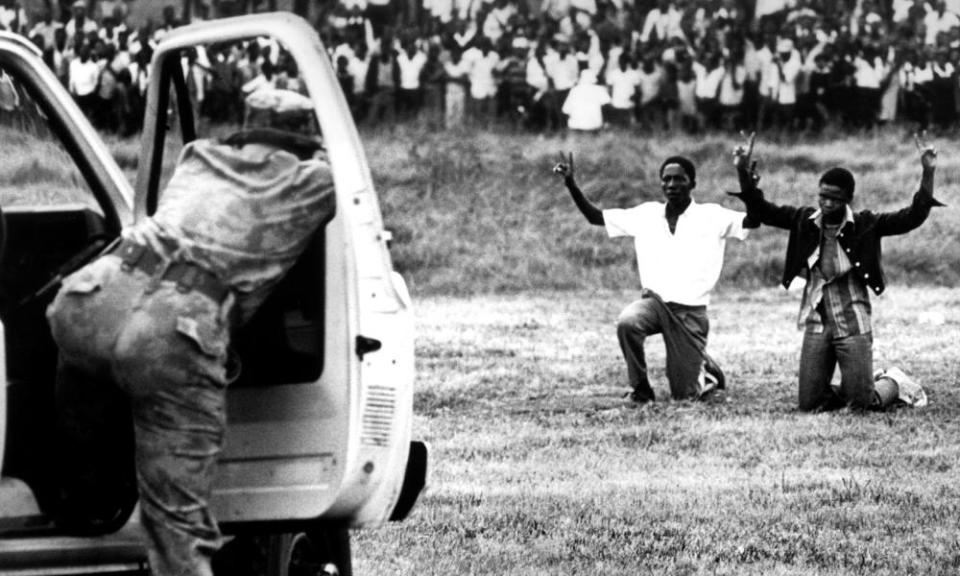

McGregor’s own teens had been spent protesting against the injustices of apartheid that were the legacy of this violent history. As a student at Cape Town University she was thrown into jail for a night, and had to be rescued by her father, after marching in support of the Soweto Uprising. To the dismay of her devoutly Catholic mother, she writes, she had abandoned the faith for socialism and the anti-apartheid struggle. “The stain of original sin became visible – the colour of my skin, all too clear a stamp of the oppressor.”

After university she became a journalist, “but apartheid seemed invincible and increasingly oppressive,” she recalls. “Security police bugged our phones and every newsroom had at least one journalist who doubled up as a government spy.” Disheartened, she decided to move to England, and a job at the Guardian, until her mother’s diagnosis with dementia persuaded her to return home in 2002, where she pursued a new career as an author of nonfiction books.

It was a time when the euphoria about Mandela’s release and the repeal of apartheid was starting to curdle into disillusion, crime and violence. In 2008, when her father died, she points out, 18,479 people were murdered in South Africa, most of them with many more years left to live than he had. “Although it feels like it, I am not marked out in any way.” Fretting at why she was finding herself so very distraught and unable to move on, she started to wonder if the process of truth and reconciliation that was being played out on the public stage could offer a personal resolution.

Despite opposition from her family, who were afraid of opening old wounds, she set her heart on a meeting with Thomas in the open jail to which he had been transferred for good behaviour, five years into his sentence. It was clear from the start that the prison authorities had little patience with her pestering, but she was allowed to sit in on a session in which convicted rapists were brought face to face with a rape victim, and slowly she found people willing to help her reach Thomas.

Despite all the grand words in the constitution, the lofty ideals of restorative justice are just that – ideals

Liz McGregor

Gradually, a picture emerged of a young man who, for all that he was from a close and supportive family, had got caught up with drugs and the rampant gang culture in his home town. In her father’s car on the night of the murder he had been smoking tik – the street name for crystal meth. But by the time she finally came face to face with him, prison had bound him so intractably into its gang network that he could not afford to speak the truth even if he had wanted to. In a grotesque parody of colonialism, the gang to which Thomas now belongs describe themselves as “British”. After prison skirmishes, explains a kindly ex-warder who she enlists to set up and mediate her prison visit, “you hear them say ‘We fought under the British flag’. I think this goes back to the wars against the Xhosa and the Zulus and the Boers. They see the British as good fighters.”

This is not a story with a happy resolution. “In my blind rush to confront, I had ignored reality,” writes McGregor. “What was in it for Cecil Thomas? There’d be nothing waiting to embrace a repentant sinner. He would be taken straight back to his communal cell … his only debriefing would be from gang leaders.” To survive, he had to stick to the story agreed with his accomplices – “the tired, implausible story he had told in court”.

In the months that followed, she concluded that the whole thing had been a farce. “Despite all the grand words in the constitution and in the legislation, the lofty ideals of restorative justice that theoretically underpin our system are just that – ideals,” she writes. To make it work, “efficient, ethical governance would have been required. He would have to be offered a credible alternative life, away from the gang, and treatment for his drug addiction.”

Thomas is due for parole next year and the McGregor family’s consent will be part of his passport back to freedom. The family will be consulted but won’t have the final say. She is going to leave that decision to her siblings, to whom the book is dedicated, two of whom have not yet been able to bring themselves to read it. “I feel I’ve played my part by writing this book,“ she says. Pressed on whether she feels Thomas should be released, she shakes her head, and asks, “What will be waiting for a convicted murderer? With his tattoos, his drug habit and his prison record, how will he not get involved in yet more violent crime?”

Though the pain of her father’s murder will never disappear, McGregor’s own life is far from bleak. In March 2020, shortly after a national state of disaster was declared in South Africa due to the escalating Covid pandemic, she married Alan Hirsch, a fellow campaigner from her student days, who rose to manage government policy on economics before quitting in despair over the misrule of the Zuma years, and is now an academic. They spend part of the year in London and the rest in a house by the sea, a 90-minute drive from Cape Town. Despite everything that has happened, she says, “I feel totally bound up with my country. Its pain and its anger and its yearnings are mine too.”

Unforgiven: Face to Face with My Father’s Killer by Liz McGregor is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers on 7 July

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies