'Like somebody gave me a happy pill:' Monoclonal antibodies are helping the Americans most at risk for COVID-19

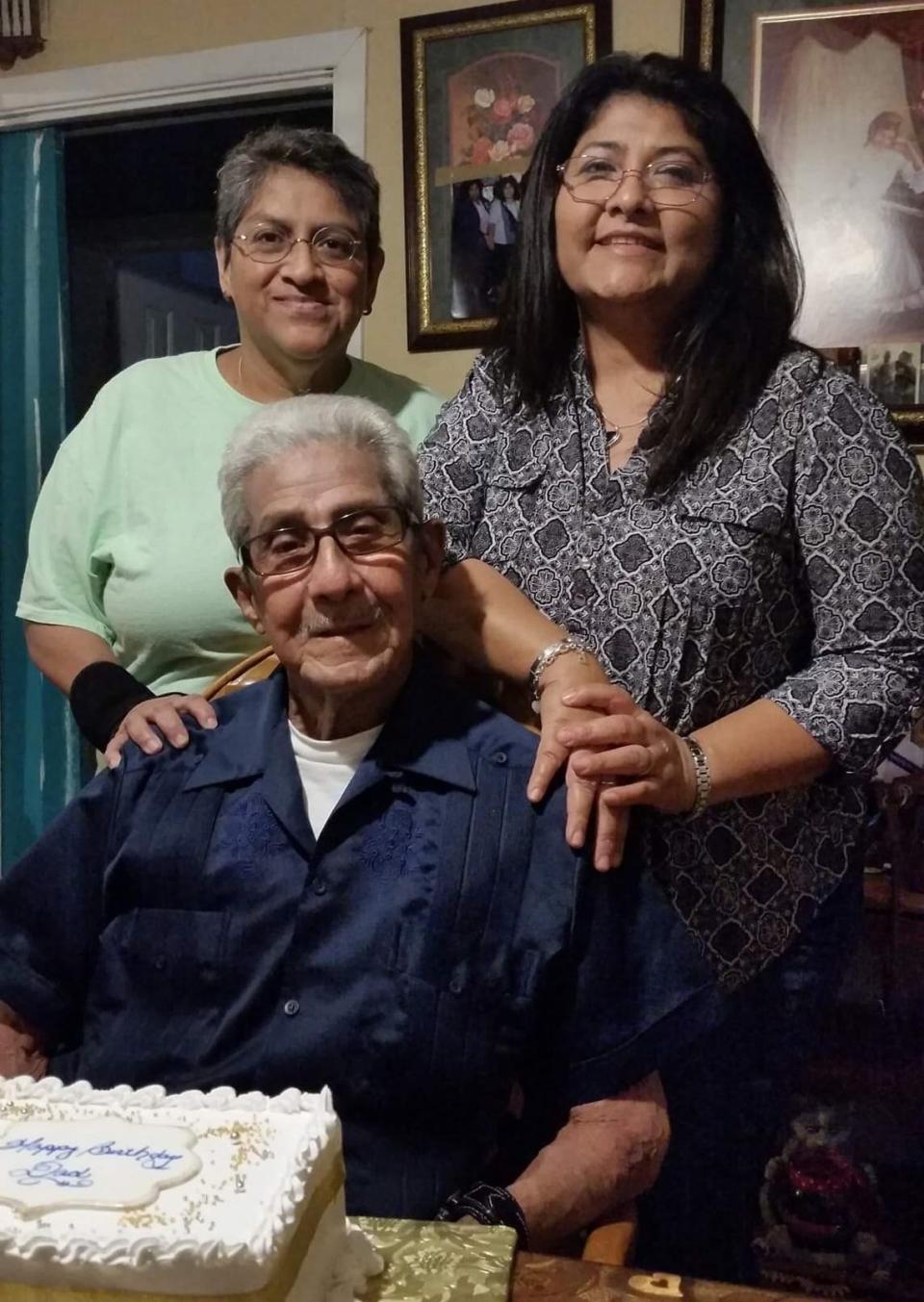

First came the sniffles. Guadalupe Ramirez dismissed them as nothing to be worried about. She popped a pill. And forgot about them.

Next came the searing back pain. That was easy to dismiss, too. She'd had rheumatoid and osteoarthritis for more than a decade, and recovered from a brain tumor in 2018. She was used to pain.

But she called her doctor anyway to report the new flare-up and its unusual location along her spine.

Related: How antibodies in recovered COVID-19 patients could treat others

Ramirez thought the doctor was being silly when she suggested getting a COVID-19 test. Ramirez had barely left the house in months. But the test came back positive.

Now, her doctor became insistent: Get monoclonal antibodies and get them fast.

Although it was nearly an hour's drive to downtown Houston from her home near Clear Lake, Texas, two days later, on a Friday in January, Ramirez made the trip.

It may have saved her life.

"By Saturday, I wanted to go jogging," said the 55-year-old former probation officer. "I woke up like somebody gave me a happy pill."

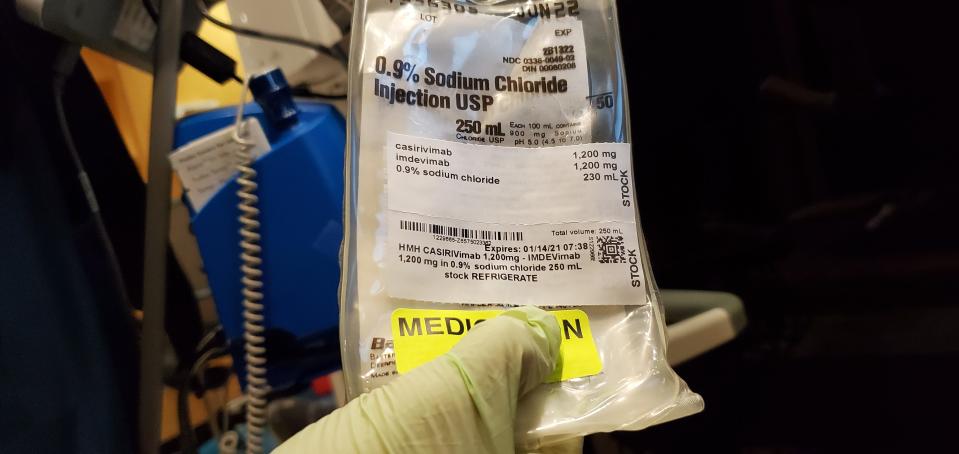

Monoclonal antibodies, which provide extra immune soldiers to help the body fight off COVID-19, are aimed at people like Ramirez, who are at high risk for serious disease because they will likely have trouble fighting off the virus on their own.

Former President Donald Trump credited them for quickly restoring him to health when he caught COVID-19 last fall. He called on the government to provide free doses to any high-risk American who needed one.

As of Wednesday, the government had bought nearly 1 million doses of monoclonals from the two companies that have authorized products, Regeneron and Eli Lilly, and has made them available to 5,800 sites across the country.

Many hospital systems, particularly those in large urban areas, have widely adopted the drugs, but still, only 43% of the federally funded doses have been used in patients, according to the department of Health and Human Services. The remaining doses sit on pharmacy shelves.

Last month, the Biden administration announced a $150 million plan to improve access to the drugs, particularly among vulnerable people.

Delivering monoclonal antibodies has been challenging, requiring a extended infusion and an another hour of observation, as well as a dedicated space, away from other people who might catch the disease. Many hospitals struggled to set up such infusion centers when they were needed most, in early January at the height of the U.S. pandemic.

On Monday, Regeneron released trial results showing that its antibodies, called REGEN-COV, can be delivered via four near-simultaneous shots, rather than an extended infusion, which should make the drug easier to deliver.

The drugs, which are considered safe for most people, already have become more accessible, doctors say. And they work well, when a patient or doctor asks for them early enough in the disease course.

"We're finally getting them in to people," said Dr. Daniel Griffin, an infectious disease specialist with New York-based healthcare provider ProHEALTH.

Getting monoclonals into arms

Several changes have happened since early this year to get more monoclonals into patients, Griffin and others said.

Most importantly, he said, research has shown that the drugs are effective, helping 80% to 90% of patients who receive them to avoid hospitalization or worse.

"It's one of those therapies where you don't need a statistician to tell you it makes a difference," Griffin said. "You're seeing a patient 36 hours later, saying 'I feel great!'"

The Food and Drug Administration also allowed health care centers to set up separate monoclonal antibody infusion centers, so the drugs don't have to be administered in a busy emergency room anymore.

"These people are at the height of their infectiousness," Griffin said. "You do not want to sit them in a room, much like an emergency room, with people who are most vulnerable."

The FDA also allowed in-home infusions, with trained personnel coming to the patient's home to deliver the drug.

"So now we have multiple avenues of access all allowing you to get therapy within 24 hours of thinking this is something required," said Griffin, whose own health care system provides them in a tent next to the emergency room.

The federal government also continues to increase the types of sites where the drugs are available, including urgent care facilities, doctor's offices, nursing homes, assisted living facilities, health centers, correctional facilities and dialysis centers, HHS spokesperson Gretchen Michael said in an email.

Griffin said more research is needed to know whether it makes sense to provide monoclonal antibodies to those with less than the highest risk for severe COVID-19, or whether they can prevent symptoms of "long COVID," which can linger for months after an infection.

According to its FDA authorization, monoclonal antibodies are recommended to be used in adults who are over 65, immunocompromised, have a body-mass index of 35 or above, chronic kidney disease, diabetes requiring medication or coronary artery disease.

"Everybody in our medical center who (tests positive for COVID-19) is evaluated for these criteria and immediately contacted," said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in Nashville, Tennessee. "We are assiduous about that."

Vanderbilt has treated more than 1,400 people with monoclonal antibodies since late last year, and believes it has cut its hospitalization rate by more than half, Schaffner said.

"We're really quite convinced that they are keeping people with risk factors for serious disease out of the hospital," he said.

Give 'em early

The key to getting monoclonals to work is to get them fast.

Studies have shown that patients hospitalized with COVID-19 don't benefit from the drugs, but people within a few days of first symptoms do.

"Time is of the essence," said said Dr. Howard Huang, medical director of the lung transplant program at Houston Methodist Hospital in Texas. "If you're combatting a virus and trying to inhibit its multiplication, we're talking about every hour, every day you wait that makes a big, big difference."

At Methodist, they set up a system to have pharmacists call people right after their diagnosis to encourage and educate them about the drugs' potential benefits.

Monoclonal antibodies are expected to continue to be useful even as most people are vaccinated, Huang said. Those who are immunocompromised, like his lung transplant patients, are unlikely to get full protection from vaccines, and are at high risk for bad outcomes if they catch COVID-19. There also will be people who decline vaccination but then get sick.

Getting an infusion early in their infection could be lifesaving, he said.

Huang and his colleagues have treated nearly 4,000 patients with monoclonal antibodies, most during Houston's January surge. They are contributing data to a national consortium which plans to aggregate information to eventually identify who benefited the most from monoclonal antibodies.

Because the drugs, which would normally cost about $2,000-$2,500 for a single-dose treatment, are provided for free and widely distributed, monoclonal antibodies should be made rapidly available to anyone at high risk, regardless of their ability to pay, Huang said.

"It's not something that's only available to rich and influential people," he said. "As a society we need to make sure everybody has equal access to that, especially the underserved population."

But access remains a problem for many, he said.

The business of monoclonals

Two companies, Lilly and Regeneron, have monoclonals already on the market. Regeneron started with its two-drug cocktail, REGEN-COV, and Lilly now has added a second monoclonal to its original drug, bamlanivimab, to provide more protection against COVID-19 variants. On Friday, the company announced it would no longer provide bamlanivimab alone.

Although experts have warned the variants might make monoclonals less effective, the cocktails have kept that from happening so far, said Regeneron spokesperson Alexandra Bowie.

"REGEN-COV remains potent against the variants first identified in Brazil, South Africa, New York, California and the U.K.," she said via email.

The company has delivered about 300,000 doses of REGEN-COV under its initial contract with the U.S. government and is making supply for the second agreement, which will provide at least 750,000 more, Bowie said.

The authors of federal guidelines for use of monoclonals expressed some concern about Lilly's combination proving less effective against many of the viral variants, though it appears to remain effective against the B.1.1.7 variant first seen in Britain.

GlaxoSmithKline, in collaboration with Vir Biotechnology, submitted a request to the FDA on March 26 for a monoclonal antibody of their own. They hope to receive authorization soon to provide a one-time, two-shot treatment, said Dr. Amanda Peppercorn, vice president clinical development at GlaxoSmithKline.

The companies believe their antibody will work on its own, regardless of the variants, she said, but also is studying it in combination with Lilly's bamlanivimab in case that proves more effective in the future.

"The pandemic has shown that monoclonal antibodies are a very rapid solution because of their predictable safety and dosage prediction – you can really model out how they're going to work," Peppercorn said. "Because they're part of the human immune system, they're a very safe type of approach for a pandemic."

Monoclonal antibodies are similar in theory to convalescent plasma, in which patients are given a blood product from people who have recovered from the disease. Unfortunately, with COVID-19, infected people seem to make vastly different levels of antibodies, Peppercorn said, so while some doses of convalescent plasma may be useful, it has not proved effective overall.

By contrast, monoclonal antibodies, which originate in recovered patients, are selected for potency, she said, and they deliver a consistent dose.

GSK and the other companies also are testing monoclonal antibodies as a prophylactic therapy, to prevent infections in people who have been exposed to the virus and are high risk for severe disease.

Currently, monoclonals are believed to provide protection for about three months.

Adagio, a biotechnology company based in Massachusetts, is developing a monoclonal it hopes will protect people for at least six months.

With clinical trials launched this week, their drug uses a different target on the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, which they expect will remain useful against other variants as well as other coronaviruses, said company CEO and co-founder Tillman Gerngross. Their antibody, called ADG20, is also more potent and so could be administered via a single shot, rather than an infusion or a multiple-shot regimen, he said.

The company expects to submit a request for authorization to the FDA late this year.

For her part, Guadalupe Ramirez remains a big fan of monoclonal antibodies. She wants everyone at risk for severe COVID-19 to learn about and get them.

"Whatever is in this medication has kept people going. I don't know what it does, but you're good," she said. "The thing is to try it right away."

Contact Karen Weintraub at kweintraub@usatoday.com.

Health and patient safety coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from the Masimo Foundation for Ethics, Innovation and Competition in Healthcare. The Masimo Foundation does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: COVID-19: Monoclonal antibodies are 'happy pill' for at-risk Americans

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies