Should you snitch on your neighbours for flouting physical distancing rules? Here's some advice

Removed from the current context, it sounds like a Cold War-era story from behind the Iron Curtain: a ban on gatherings, the possibility that police might enforce that ban with arrests, members of the public ratting each other out.

But during the COVID-19 lockdown, Quebecers, like billions around the world, are dealing with a reality defined by rules that prohibit basic human social behaviour.

"In many cases, we are suspicious when the government restricts individual freedoms," said Jocelyn Maclure, a professor of philosophy at Université Laval. But in extreme situations, attitudes can change.

"The fact that there's a wide social consensus on social distancing measures and confinement and so on — it seems people understand the need for these restrictions."

But navigating these restrictions remains a complex, stressful task. Quebecers are having to find ways to abide by strict rules and how to deal with people who break them.

There is no shortage of examples of people ignoring the rules. In Sherbrooke on Thursday, police broke up a student party at a private residence, dispersed a gathering of six people in a park, and shut down three non-essential businesses that remained open.

In Gatineau, police stopped a gathering in an apartment Wednesday that cost its hosts $1,200 in fines.

After the decree against indoor and outdoor gatherings was made public last Saturday, Montreal police received more than 200 calls in less than two days, said SPVM Inspector André Durocher. The provincial police say they have also received calls about people gathering in groups.

Do you snitch on your neighbours if they have a gathering?

Even now, reporting people to the police "should not be taken lightly," said Maclure, who is also the president of Quebec's commission on ethics in science and technology. But in the coronavirus situation, he said, "the stakes are very high."

(Note: if a situation does warrant calling the police, they are pleading with people not to call 911, but to contact their local police station.)

Montreal police haven't issued any fines or made arrests, Durocher said, and they have no intention of forming "a squad to monitor social distancing measures." He said most people seem to understand that the crisis requires a collective effort.

"For this to be over, everybody has a responsibility," said Durocher. If the public does its part, that will "make it easier on authorities to concentrate on other issues," rather than "telling people that they should be respecting" distancing rules.

Maintaining 'good faith among neighbours'

Where it can sometimes break down is where there's uncertainty.

People have reported on social media that they've been abused and shamed for being out with their children. Vincent Marissal, the Québec Solidaire MNA for Rosemont, said his four kids were confronted — from a safe distance, but confronted all the same.

"The four of them went out to get some fresh air," Marissal said. "They were scolded by a lady, who told them they were breaking the law and threatened to call the police. My 17-year-old daughter had to explain to her that they were siblings."

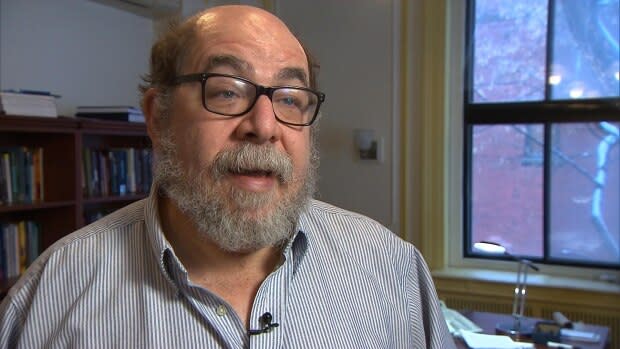

In an email to CBC, Daniel Weinstock, a philosopher and professor at McGill's faculty of law, said it seems reasonable to call the police if there's clearly a party happening next door. But it's otherwise worth maintaining a "certain amount of good faith among our neighbors" and assuming small groups out walking together are part of a family.

"Informing against our neighbors is highly corrosive to social relations, in ways which may continue to have echoes after this crisis is over," Weinstock said.

"Bottom line: probably a good idea to 'snitch' only in clear, unambiguous cases."

Maclure similarly advised that — except in cases like parties that show clear disregard for the well-being of others — calling the authorities should be a last resort.

"I would surely try to talk to them first — from a distance, of course."

Stepping up is crucial

Doing that may also seem challenging. Nancy Kosik, an etiquette and protocol consultant, said you should be polite, assertive and ensure your body language is friendly. Don't yell from your car. Maintain an appropriate distance, and maintain a positive tone.

You should greet the group politely, Kosik said, and then say something like, "I don't know if you've heard, but the government is urging us to speak up if we see people putting themselves at risk. I'm asking you to please wrap up and go home for obvious reasons, even if you're feeling fine."

Once you've said your piece, Kosik said, stay there. "Don't just leave. See them disassemble their group. Reinforce that you mean what you say."

It's a strange time, Kosik acknowledged, but that makes it all the more crucial that people step up and intervene.

"The more people who show that they're speaking up, the more people will understand how important this is," she said.

"The more we do our part and are effective in doing it in a way that does not cause confrontation, the sooner we can get back to our normal lives."

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies