Silicon Valley Bank’s implosion rattled Miami’s growing technology sector

In seven years of investing in early-stage technology startups in Miami, Chris Adamo, 42, has never had a tougher month.

Between March 8 and March 10, the co-founder of Flamingo Capital and his partners hurriedly contacted each of their portfolio companies to check whether they had deposits at Silicon Valley Bank. News spread that the California niche bank catering to startups was in deep financial trouble. They urged their eight Miami startups who were clients of the bank — which opened an office in Brickell in late 2021 — to urgently wire their money out and to open new accounts at multiple larger banks.

Four of the eight companies could before the bank collapsed on March 10, said Adamo, who moved here from New York in 2012. He also asked other investment firms, if they could wire fresh capital into those startups’ new accounts amid the massive uncertainty among regional banks nationwide prompted by the bank’s abrupt failure. They did, but those were “definitely the scariest days for us” as investors, he said.

Adamo’s firm certainly wasn’t alone. At least half of the tech startup businesses operating in Miami apparently had their money in SVB, according to a reliable estimate given to the Herald. And the bank’s managers in Brickell were reaching deeper in the Miami area to sponsor tech-related events. In one such case, it turns out the bank hasn’t delivered the city of Miami $15,000 it promised to invest in the winning Black-run startup firm after a February entrepreneurship contest city officials held.

Miami’s tech and finance sectors surged the past two years in a pandemic-induced expansion. Entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and private equity titans moved to Miami and helped transform the city. Many came from New York and California. And last year, Miami posted a sharp increase in venture capital dollars invested and number of venture investment deals done, bucking softer trends in traditional tech hubs like Boston, the San Francisco Bay Area and nationally. Miami was different, excited newcomers and locals supporting or working in the blossoming tech ecosystem proclaimed.

Yet, the aftermath of Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse underscored that the larger the technology and finance sectors become in Miami, the more the city and surrounding South Florida area get exposed to significant blowback — even when the epicenter of an implosion from the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history occurred thousands of miles away on the West Coast. Miami’s continuing goal of going big in tech comes with high risks of unintended consequences.

“We’re not insulated from any of that stuff,” Adamo said of the bank’s misfortunes. “We’re not ever going to be an island.”

‘It’s part of capitalism’

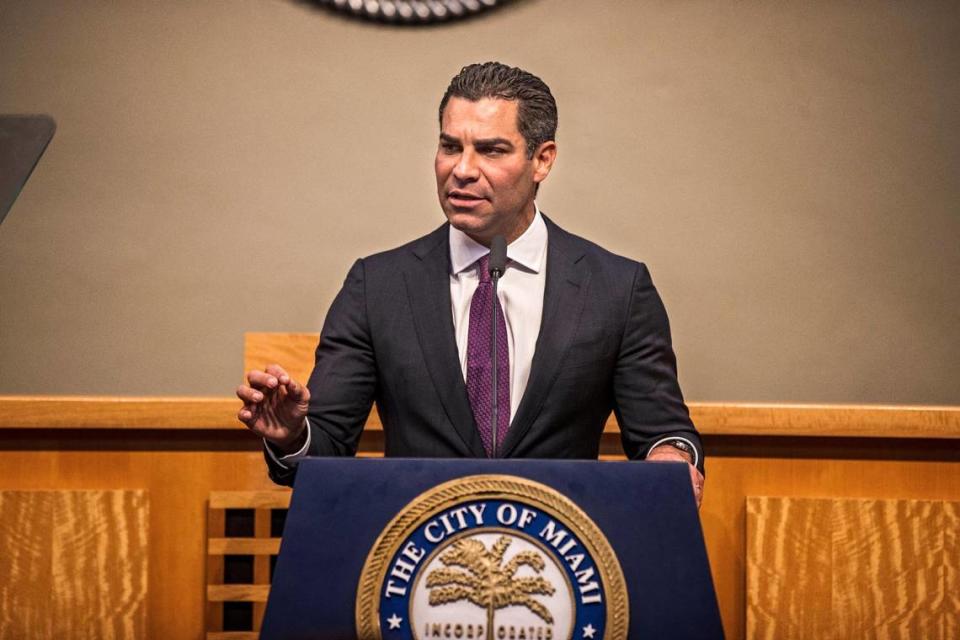

Miami Mayor Francis Suarez has been particularly bullish on tech, determined to establish a sustainable, thriving tech cluster here. He’s played a large part in accelerating the city’s massive tech and finance expansion, since his now-famous tweet in December 2020. Suarez responded to a Twitter poster in the throes of pandemic shutdowns in California, suggesting bringing Silicon Valley — the startups and investors, not the bank — to Miami with a simple tweet of his own: “How can I help?”

In a rare interview last week in City Hall, the mayor said, “A lot has gone through my mind” since Silicon Valley Bank’s failure. However, he has no second thoughts on going all-in on tech.

Failures or setbacks, he said, are part of the free-market system — all the more with startups — and he approaches his tech evangelism with that assumption.

“It’s part of capitalism. You invest, you take a risk,” the mayor said. “Sometimes you succeed, sometimes you fail. You learn from failure and you build again, and you try not to make those same mistakes.”

But he said when you juxtapose that with politics, “everyone wants to tag the failure onto you and make it seem like you’re a failure as opposed to a project that fails.”

Suarez said a key part of his job is attending local events to celebrate the arrival or opening of new businesses, including tech and finance companies. Whether some of those firms later go under does not spook him.

“The world has never been more disruptive,” he said. “So the velocity at which a big company can be disrupted out of existence as we’ve seen is incredibly fast. So that creates a tremendous amount of risk, but what are you going to do? You can’t just sit back.”

At the same time, the mayor said he would gather even more information when new ventures emerge in Miami.

“I think I’m going to continue to do more and more due diligence,” he said. “I think that’s part of my learning process, so I think you have to grow and learn on your own, too.”

Widespread exposure

After the collapse, national media reported the federal regulators had Silicon Valley’s operations in its crosshairs and under review for a few years. Still, the bank’s demise was unexpected in Miami’s tech arena of investors and startups — and around the country.

Without warning, they’ve had to reckon with shock and varying degrees of disruption to their firms.

Capsule, a Miami company that uses artificial intelligence for businesses to make videos, started in 2021 and was backed by Flamingo Capital. It was also a customer of the now-infamous California bank named for the part of the state where it made its home.

“It was not seen as risky to hold your money in a 40-year-old bank with the best reputations in the valley [Silicon]” co-founder Champ Bennett posted after someone on Twitter criticized him.

Plus, Bennett said SVB was one of the only banks that would work with his startup, offering products such as a corporate credit card without requiring personal guarantees from company founders.

Although Bennett is one of the few to admit it publicly, at least half of tech startups in Miami were likely commercial banking clients of SVB, according to an estimate provided to the Herald by Juan Pablo Cappello, a longtime Miami entrepreneur, business attorney, and founding partner of PAG Law. He declined to discuss specifics, citing attorney-client privilege.

One reason for that is because noteworthy venture capital investment firms, such as San Francisco Bay Area-born Atomic and Founders Fund, were also SVB clients and both proudly set up shop in Miami during the pandemic. They have offices in Wynwood. Atomic and many of its portfolio companies had accounts at SVB, said Chester Ng, a general partner in the firm’s Miami office.

Billionaire Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund pulled out its money a day before SVB failed.

“Thursday morning it was clear we were in the middle of a bank run, and we reacted in line with our fiduciary duties,” said Neil Ruthven, Founders’ chief financial officer, in a statement sent to the Herald.

The firm’s partners like billionaire Keith Rabois, a former PayPal executive, have strongly promoted Miami’s tech scene. And it was a principal at Founders who sent the prophetic tweet in December 2020, to which mayor Suarez responded.

Miami’s tech old guard not spared

Old-timers who have championed the city’s potential as a tech oasis for more than a decade also were squeezed by SVB.

Miami native Melissa Medina, co-founder and president of eMerge Americas, which has held the largest homegrown annual tech conference since 2014, told the Herald eMerge was a client of the bank for over five years. After a stressful several days, “We were able to access our funds and didn’t incur any losses, thankfully,” she said.

eMerge had also collaborated with the bank and its employees, and she said the bank’s former local representatives “spent a lot of time and resources on the growth” of Miami’s tech sector. Emblematic of the emotions of many in the tech world, Medina said, “It’s difficult and unfortunate to see how this unfolded and what transpired.”

Demian Bellumio, a longtime tech founder who graduated from Florida International University in 2000, said he personally kept three accounts with SVB. Miami Tech Life, an organization he helped start, banked there, too. He said he was initially able to withdraw some money, but other wires did not go through. After federal regulators stepped in, he got access to all of his money. (Within 48 hours of the collapse, the U.S. Treasury stepped in and insured all of Silicon Valley’s depositors, including many that had more than the $250,000 cap the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. insures at all federally charted banks.)

Bellumio maintains a deep appreciation for the bank, and in fact has since returned his money to the temporary SVB Bridge Bank under federal government management, “to support the bank” as government and U.S. banking leaders continue trying to sell it to one or more buyers. So far, banking giants JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo have decided against absorbing what’s left of SVB.

Even Miami real estate investors apparently were caught in the demise. Rialto Capital, based on South Biscayne Boulevard, was raising a new fund and so had asked investors to put money into its SVB account by the end of the week the bank collapsed, according to two individuals with direct knowledge. It was unclear what ultimately happened. Multiple phone calls by a Herald reporter to Rialto officials yielded no response.

SVB’s internal missteps

Based in Santa Clara, California, Silicon Valley Bank operated for four decades. Its growth rocketed the past decade. During the ongoing pandemic that began in spring 2020, clients’ deposits at the bank surged as tech boomed. SVB put much of that money into long-term U.S. treasury bonds, normally a conservative investment. Then, last year the Federal Reserve started a series of interest-rate boosts, trying desperately to thwart stubborn inflation still gripping the country and squeezing consumers’ wallets. Therefore, the value of those bonds SVB held, but couldn’t liquidate, plunged.

SVB managers did not adjust their investment strategy to offset risk. Meanwhile, the tech sector nationally slumped last year, and so startups increasingly withdrew money from their accounts at the bank, needing it during tough times to keep making payrolls.

After SVB said early in the week it blew up it was seeking to raise fresh capital, panic ensued. The next day alone, customers withdrew $42 billion. It was clear there was a depositors’ run on the bank underway that neither the bank nor elected leaders — or anyone could stop. Uncle Sam had to rescue SVB’s depositors to soothe the fears and keep mayhem from engulfing potentially much of the U.S. banking system.

Challenges ahead

In the aftermath, for Miami’s tech scene, “it’s not going to be quite as easy as it’s been the past year and a half,” said Scott Kimball, chief investment officer of Miami-based Loop Capital Asset Management. “When you talk about the tech or finance industries at the systemic level, you can’t operate in a silo.”

In addition to the stress and disruption of the past three weeks, tech startups face other likely financial challenges, according to investors, analysts, and founders.

“[This] will make things harder,” Flamingo Capital’s Adamo said.

Venture capital firms will have a harder time finding investors, raising funds, and have to be more careful about which startup companies they back.

And overall, financing costs will increase, and credit will become more restrictive. “When we see these bank failures or bank stresses, credit conditions tighten for all consumers,” Kimball said.

This is all occurring during a slow start Miami startups are having so far in 2023. After the record year in 2022, in January and February Miami drew $78.6 million in venture capital financing for early-stage firms, about one-tenth of what it received in the first two months last year, according to research firm PitchBook. And the number of startups that secured venture investment deals during the past two months is only half of the number of deals in Miami in the same period a year ago. Tech startup hubs in the Bay Area, New York and Austin have also stumbled out of the gate this year.

Another spillover effect here is that SVB no longer will be sponsoring local community events around Miami.

On February 7, the city held the Black History Month Pitch Competition with co-sponsors eMerge Americas and SVB.

“We are proud to partner with eMerge and Silicon Valley Bank to present the Black History Month Pitch Competition,” Suarez said in January. “The pitch competition is an important step towards promoting diversity and inclusion in the tech industry and supporting Black entrepreneurship in Miami.”

SVB officials had committed to provide $15,000 to the startup firm winner.

Mayor Suarez said in last week’s interview he now assumes the failed bank can’t honor its financial pledge, and his office is seeking a replacement sponsor.

Erick Gavin, executive director of Venture Miami, a City Hall arm focused on growing the expanding tech sector, was present during the interview with Suarez and said city officials already are looking for another partner to make good on the $15,000 sponsorship. Gavin said, “100%” it will be covered.

Optimism amid anguish

Suarez, Gavin and others remain convinced Miami’s tech hub will prevail, remain attractive to outsiders and survive the SVB financial wreckage.

“There will be some short-term disruptions,” said Mason Williams, managing director and chief investment officer of Coral Gables Trust. However, “Businesses are still going to flock here. I don’t think that’s going to change.”

Even Adamo, the bruised venture investor in Miami, is positive over the long haul. On March 15, the Wednesday after SVB collapsed, he returned to the weekly tech happy hour at the Freehold in Wynwood that he helped start and has become an influential gathering drawing old-timers and new arrivals in the growing innovation ecosystem.

“Overall, I’m personally not stopping my investment thesis, and my cadence has been pretty steady for the past few years,” he said.

Still, SVB’s failure offered a bitter reality that the larger Miami’s tech hub becomes, the more intertwined it will be with any financial catastrophe anywhere in the nation, and around the world. Throw in the difficult macroeconomic environment and lingering recessionary fears.

“It’s going to be difficult for any tech sector, anywhere in the global economy to not be affected by this,” Loop Capital’s Kimball said.

Adamo concurred. “We’re equally as impacted as New York or San Francisco is. That is going to be the case forever, I think.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies