A shot in the dark: How AJ Lawson’s family, upbringing prepared him for NBA leap

The basketball goal still stands on the farm in Summerton. It might need a new rim, but its foundation is sturdy.

Jerome and Anthony Lawson grew up on that farm, raised by their grandfather, Moses Lawson, and grandmother, Mary Gertrude Boatwright Lawson. They never knew their father, but Moses and Gertrude cared for them like their own sons.

The boys’ mother lived in Baltimore, where Anthony spent the early years of his life. Jerome, 60, still remembers sitting on his tricycle, with a toy shovel and little white pail, on the day Anthony moved down to Summerton. When Jerome stood up to empty the dirt from his pail, Anthony — his junior by about 18 months — sat down on Jerome’s tricycle.

The boys brawled instantly. And like any pair of young, competitive brothers, they scrapped and fought all the way through to their high school years at Scott’s Branch in the late 1970s.

Summerton is a small, rural town in Clarendon County with a population of about 1,000. Moses and Gertrude owned a farm and lived off their land, putting both boys to work. Jerome and Anthony would spend their days pulling plows, cropping cucumbers and sweet potatoes, stringing tobacco up in the barn to cure it. Southern at heart, Jerome didn’t mind getting his hands dirty, milking cows, working with chickens. Anthony was more of a city boy, and still is.

Though their personalities would often clash, the brothers found common ground in their love for basketball.

Every night, after their farm work was done, Anthony and Jerome would meet at the basketball hoop and put up shots. There were no lights outside; they could barely see the rim. It didn’t matter. Night after night. Shot after shot. In the dark.

Whenever they had the chance to play with other boys around town, in broad daylight, they wouldn’t miss.

“People were like, ‘Man, you’re not even looking at the rim,’ ” Jerome said, laughing. “We knew where the rim was. If we go and sit in that corner and you threw that ball up, it’s coming down, man. We just got good at that.”

After high school, both Jerome and Anthony enlisted in the Air Force. Jerome played basketball on base in Korea, earned a second-degree black belt in Hap Ki Do, and he’s lived in Rock Hill for the past 17 years. True to his city roots, Anthony moved back to Baltimore after serving in the Air Force, then migrated farther north to Ontario, Canada, eventually becoming a citizen.

It has been decades since the brothers have lived in the same country, yet all these years later, basketball continues to tie them together.

Anthony’s son, Anthony Lawson Jr., moved from Brampton, Ontario, down to Columbia three years ago to play Division I basketball. Decades after his father and uncle played ball in the pitch-black night on a farm, A.J. played under the lights at Colonial Life Arena. He etched the Lawson name into the South Carolina basketball record books.

In his three-year career with the Gamecocks, Lawson scored 1,153 points on 40.7% shooting from the field, becoming the 47th player in school history to join the 1,000 point club. He ranks eighth in program history with 164 3-pointers.

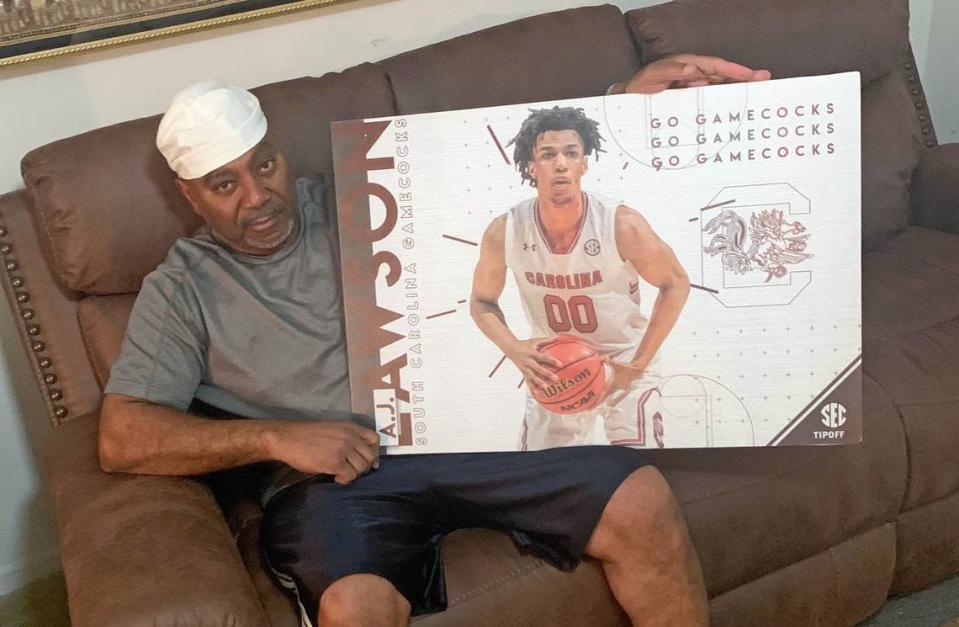

All the while, his father and uncle have looked on with pride, living their childhood basketball dreams through him. Jerome attended every home game A.J. played at Colonial Life Arena and let his nephew stay with him at his Rock Hill home whenever he needed an escape. Anthony and his wife, Kathleen Parchment, watched from afar in Canada, texting and calling him every game day. Anthony has coached A.J. since he was 4 years old.

“It wasn’t easy for us blue-collar working parents trying to keep him up in the basketball journey, as you know how costly it is,” Anthony said. “He was always an underdog and overlooked. He worked hard to get where he’s at. He’s still got a lot to offer in his growth with an unlimited upside that I trust everyone will see in his future. We know he’ll never stop working hard to achieve.”

A.J.’s journey is only just beginning. On Monday night, Lawson declared for the NBA Draft and signed with an agent, ending his Gamecocks career. In his draft announcement, Lawson acknowledged that “there is great room for improvement, and that is all that I’m committed to — reaching my potential — and I believe I’m 100% ready.”

Though not a finished product, Lawson is only 20 years old and coming off a career-best junior season. Even with the stops and starts caused by COVID-19, Lawson finished fifth in the Southeastern Conference with 16.6 points per game and led the conference with 2.8 3-pointers per game. He landed second-team All-SEC honors.

At 6-foot-6, 177 pounds, the versatile guard has room to grow into his frame and has raw athleticism that he has yet to tap into on the court. Like his father and uncle before him, Lawson possesses an insatiable work ethic and a knack for sinking 3-pointers, establishing himself as one of the premier shooters in the SEC.

But does he have the confidence to shoot the ball in the dark?

Stuck in quarantine

It’s late December 2020, and A.J. Lawson is sitting in his Columbia apartment. Eyes closed. He’s holding a basketball he found in the trunk of his car.

Over and over again, Lawson imagines his feet lifting off the court, the orange ball arcing high in the air, then dropping straight down through the cylinder below. Again and again. Shot after shot.

The Gamecocks are in quarantine. From December into January, positive COVID-19 cases shut the team down on three separate occasions, postponing or canceling seven games.

For weeks, Lawson and roommate Justin Minaya couldn’t leave their apartment. They couldn’t go to the gym and lift weights or go for a run around town. They couldn’t put up shots at the Colonial Life Arena or at a nearby court somewhere. They were stuck inside together, just like all of their teammates.

This wasn’t what Lawson had envisioned for his junior season. Coming off an up-and-down sophomore campaign, Year 3 was supposed to be the year Lawson took a leap as an NBA prospect, the year he’d help lead the Gamecocks back to the NCAA tournament. Instead, USC played just three games — all on the road — before shutting down.

In the last of those three games, on Dec. 5, South Carolina took future Final Four team Houston to the wire, leading the Cougars at halftime before falling late, 77-67. Lawson had his worst game of the season that night, going 2 for 10 from the field and scoring just five points. Days later, the Gamecocks announced positive COVID-19 tests in the program and halted team activities.

“He did not play well at Houston — and that just sat in his gut,” head coach Frank Martin told The State. “I had never asked him about that, but I’ve been around him for three years, so I’ve got him figured out pretty good.”

In past years, Lawson might have stewed and stewed over that game, letting it drag him down. As a sophomore, coming off an SEC All-Freshman year, Lawson found himself at times overwhelmed by the pressures and expectations that come with a starring role on a Division I team.

“Where he was last January, mentally, he was at a very low point of his career, because he was expected to basically be the face of the franchise, be that guy for that program,” said Tariq Sbiet, a confidant and mentor figure for Lawson. “But he learned how to fight through that, and that’s the thing I’m most proud of him about is the fact that he’s fought through it all.”

Along with his brother, Elias, Sbiet is the co-founder of North Pole Hoops, a Canadian prep scouting service that launched in 2011 with the aim of helping traditionally overlooked Canadian high school prospects gain exposure and connect with D-I programs. Over the past decade, the NPH brand has grown to sponsor showcase events and launch the National Preparatory Association — the prep league Lawson played for as a teenager.

Through his work with NPH, Sbiet has been able to watch Canadian NBA players like R.J. Barrett and Shai Gilegous-Alexander blossom in front of his eyes. He remembers being in awe of a young Jamal Murray, one of the more advanced Canadian players Sbiet has seen in terms of the mental game.

When the second-year expectations started catching up with Lawson, Sbiet introduced him to the meditation and visualization techniques he saw Murray use.

“I really started doing it last year, like towards the end of the season,” Lawson told The State. “And I feel like it’s helped me throughout this year, because if I didn’t start visualizing I feel like I probably wouldn’t have as much hope.”

Lawson and Minaya could’ve sat in their apartment through December and January and sulked. With the coronavirus spreading through the program, they could’ve given up on the season entirely. Instead, Lawson chose to begin each day with positivity, praying to God and thanking him for his health and the opportunity to play college ball.

Like Sbiet taught him, he’d close his eyes and imagine himself on the court, imagine himself thriving. He’d picture the ball falling through the net. He’d watch film, NBA highlights, guys like Steph Curry raining 3-pointers and think to himself, “I can do that.” Not out of arrogance. Out of self-belief and determination.

For weeks, Lawson relied on nothing but his own imagination. He and Minaya spent their days doing squats and push-ups in their apartment. They’d take turns dribbling a ball, annoying their downstairs neighbors. The closest they came to participating in actual basketball activities was when Minaya managed to track down the elusive Playstation 5. The teammates created video game versions of themselves in NBA 2K21 and played together online.

“My player’s a scoring machine,” Lawson said, grinning. “I try to do flashy dunks and shoot the trey ball all the time.”

As it would turn out, the real-life Lawson can be a scoring machine, too.

On Jan. 2 the Gamecocks were finally able to resume action, hosting Florida A&M for their first home game of the season. USC played despite only having nine available players and despite putting in only a couple of light practices after a month-long quarantine. The Gamecocks were not in basketball shape. Not even close to it. Players talked about gasping for breath late in that game and fighting off cramps.

Yet Lawson was undeterred. After weeks of fantasizing about 3-pointers, Lawson found an open look from the corner nine seconds into the game — and drained it. The junior finished with a game-high 25 points, practically willing the shorthanded Gamecocks to a 78-71 victory.

Just four days later, the still-rusty Gamecocks hosted Texas A&M for their SEC opener. Lawson scored a career-high 30 points, leading the Gamecocks to a 78-54 win in one of his best games in garnet and black.

A day after that, the Gamecocks shut down yet again.

“He had an enthusiasm for this year, and sometimes you don’t control what’s in front of you, and there are so many things that just kind of kicked in and kind of tried to knock that enthusiasm off of him and our team,” Martin said. “And he — this is that spirit I’m talking about — he didn’t allow that moment, that chapter, to impact him.”

On the contrary, Lawson represented one of the few consistent bright spots and daily certainties for the Gamecocks in a turbulent, unprecedented season. When USC played its best basketball, Lawson was usually in the middle of it. He had moments where he was the most dangerous player on the court.

Ten days after the Texas A&M game, Lawson scored 22 points on the road at LSU while Frank Martin and top assistant coach Chuck Martin stayed home with COVID-19 symptoms. In a 13-game stretch from Jan. 2 to Feb. 20, Lawson scored at least 20 points in 10 games. His determination was visible in the aggression and decisiveness he played with, slicing toward the basket, dunking, mixing in more mid-range looks to go with his 3-point sharpshooting.

While much of the attention around the men’s basketball team centered on its COVID-19 issues and subsequent struggles in a 6-15 season, Lawson’s evolution as a player flew somewhat under the radar.

“I’m kind of disappointed to be honest,” Sbiet said. “Because I look at A.J. and I know his talent and what he’s capable of and what he’s done this year. And you look at his last three years, I’m disappointed in the sense that I don’t believe A.J. is appreciated in the whole region, in the SEC and South Carolina. I don’t feel the love for A.J.

“One thing you can’t say this year, you can’t say A.J. didn’t do his job.”

Lawson has learned to filter out negativity and outside perceptions. What he and his teammates accomplished this season goes beyond basketball or statistics. Lawson learned something about himself. What he lost in time on the court, he gained in mental toughness.

“What am I going to remember the most? Definitely the COVID tests,” Lawson said, laughing. “But as a team, I’ll remember just how hard we worked, like the trials and tribulations we went through playing without our head coach, playing without some teammates sometimes. I’m just going to remember those moments and how hard we had to work just to keep the season going and sacrifice.”

Hard work runs in Lawson’s blood.

‘My city love me like DeMar DeRozan’

In the beginning, David Cooper was irritated.

As head coach at GTA Prep in Brampton, Ontario, Cooper could never understand why he’d look over at the bench after a deflating loss and see his top player smiling or cutting jokes with the opponent.

Lawson had on-court rivals in high school, but he never had enemies. And that baffled Cooper. In his 18 years of coaching, he has never met a player quite like Lawson. Cooper thought that to be a star, to make it to the next level, Lawson needed to earn his way onto a few “hate lists.” He needed to play with more of a mean streak. An edge.

But Lawson never stopped smiling. His positivity never waned.

“At first, I thought it was because he didn’t care,” Cooper said. “And then you get to understand him and you’re like, ‘Man, this kid is tough.’ I used to try to lean on him sometimes. If we had a rough game or a rough patch, I kind of looked over at him and he smiled at you. And you want to be upset, but that smile is contagious. It’s almost like you knew everything was gonna be OK.

“And the next game and the next practice, he comes with a vengeance, and he has something to prove.”

Cooper’s perception of Lawson changed when Lawson started living with him. For a couple of seasons, Lawson boarded with Cooper and his family to maximize his basketball training. Cooper remembers the way his 4-year-old daughter, Cardavia, looked up to Lawson and how he always took the time to talk and play with her. Now 8, Cardavia still tells people about her “older brother.”

Friends, family and coaches describe Lawson as having a sort of joyful purity about him. He takes after his mother Kathleen with a quieter, more low-key personality. But that doesn’t mean he’s shy or doesn’t like to have fun — or that he doesn’t take his craft seriously.

Lawson and Cooper used to have secret workouts at 5 a.m. every day. Cooper would take Lawson to the gym and push him mercilessly for an hour — demand everything out of him. Then from 6:30 to 8 a.m., Lawson would join his teammates for a full team workout without saying a word about the work he had already done. He didn’t want to make excuses or draw extra attention to himself.

Lawson never viewed himself as a star. It took time for him to establish himself on the Canadian circuit, playing behind more physically mature players like Barrett. He couldn’t dunk a ball until the 10th grade, and he didn’t garner high-major interest until a late growth spurt pushed him to 6-6.

“Back then I was overlooked all the time,” Lawson said. “I was coming off the bench. No one was ever like, ‘Oh hey, that’s my star player,’ like I always wanted to be that star player growing up. I was never that. I always had a chip on my shoulder.

“The North Pole Hoops people, they have a showcase every year. And grade nine, I went to the showcase, and they always had an all-star game for the top-20 best players in the camp, and I didn’t make it. The next year, I finally hit the growth spurt, I made it and won MVP. That’s the underdog mentality I’ve always had.”

That underdog mentality has long been pervasive in Canadian youth basketball, which lacks the robust infrastructure of its American counterpart. But the game is growing, and recent NBA success stories like Murray, Barrett and Gilgeous-Alexander only add momentum.

Lawson counts playing for Team Canada as one of his career highlights. He takes pride in his hometown of Brampton, which is a blue-collar, working-class suburb on the outskirts of Toronto. When the Raptors won their first NBA championship in 2019, Lawson was out on the street celebrating during their victory parade. Like any kid from the Greater Toronto Area, Lawson considers Drake his all-time favorite rapper. In the week leading up to the SEC tournament, he listened to “Lemon Pepper Freestyle” on repeat.

His favorite line: “My city love me like DeMar DeRozan.”

Lawson’s Canadian roots will always be an essential piece of his story. So, too, will his time in Columbia. There’s a reason why he signed with the Gamecocks over tempting offers from Oregon and Baylor.

Lawson wanted to play for Martin, someone with an entirely different temperament from his own, someone who could bring out an edgier, tougher, more aggressive side of him. When Lawson first set foot on campus, he hardly said a word to Martin. He was skittish, afraid to make a mistake.

“When I get mad at him, it pains me because he’s such a good kid,” Martin said. “It’s just like my own children. I don’t like getting mad at them, but I have to because that’s my responsibility to help them so they’re prepared to handle reality. But that doesn’t mean I feel good about it.

“There’s some guys that I get mad at and it really doesn’t bother me as much because they’re just being knuckleheads. But A.J. is a beautiful young man, just a beautiful young man.”

Over the past three seasons, Martin has seen Lawson develop into a more complete player, particularly on the defensive side of his game, where he needed the most work coming into college. This season Lawson finished ninth in the SEC with 1.52 steals per game. His signature defensive performance came late in the year at Georgia, when he held Bulldogs guard Sahvir Wheeler to 2-of-13 shooting one game after Wheeler put up a triple-double.

Even more eye-popping for Martin was Lawson’s increased maturity and assertiveness as a junior. Late in the season, as losses mounted, Lawson met with his head coach and asked him what more he could do, how he could help his teammates.

“He’s had a heck of a run,” Martin said. “He’s a lot more vocal. He’s a lot more confident with who he is, which is part of the journey.

“You see these guys come on campus, where like him he’s 17 years old and he’s a baby, and you start seeing them come out of their shell and grow into who they’re going to become as men. And for me, that’s why I coach, so I can see guys like A.J. become comfortable in their own skin.”

‘He’s not coming back’

Moses Lawson was often mean — but he was the good kind of mean. He instilled discipline in Jerome and Anthony, taught them the value of hard labor. Though he was quick to scold, he cared for the boys, too.

Before long, he took notice of the nights Jerome and Anthony spent at the basketball hoop on their Summerton farm, taking shot after shot in the dark. One day, the boys came home from school to find a light installed above the goal.

“We were the two happiest little kids going,” Jerome recalled. “When we could actually see the dadgum rim it was like, ‘Oh man, this is a piece of cake.’ ”

Someday, the lights will turn on for A.J., too. That’s what the people close to him believe — that he has yet to tap into his full potential, that he has only shown flashes of the player he can become. As Lawson acknowledged in his NBA Draft announcement, his path to this moment has not been linear. Especially not this season.

In early top-100 prospect rankings and mock drafts from ESPN and The Athletic, Lawson is on the outside looking in, but he has time to raise his stock before draft day on July 29. Each of the last two offseasons, Lawson has participated in the draft process without signing an agent, gaining valuable feedback on the ways he can improve, from adding size to tightening up his defense.

“He was not ready to make the jump last year to the NBA Draft. I think he’s ready now,” Sbiet said. “You look at the Canadians that came before him, 6-foot-6, 6-foot-7 combo guards, R.J. Barrett, Nickeil Alexander-Walker, Shai Gilgeous-Alexander. A.J. is the best shooter of them all. And he’s maybe the best athlete of them all.

“This is not my opinion. I’ve spoken to his coaches that have coached all of them, and that’s what they say. He hasn’t displayed his full athleticism yet, and he needs to get physically stronger. That’s the next thing he needs to work on. But I bring up those names because you look at those guys’ trajectories and then you look at A.J. and the fact that he’s the best shooter and arguably the best athlete of them all — that’s exciting.”

Lawson’s draft declaration is a celebratory, full-circle moment for the whole family, even if it’s somewhat bittersweet for Jerome. For the past three years, he has made the short drive from Rock Hill to Columbia every home game to watch his nephew chase a dream, building a bond with A.J. through basketball the same way he once did with A.J.’s father.

On Aug. 4, 2019, Jerome’s wife died. Laronistine Dyson Lawson was a kind, intelligent woman who wrote books on criminal justice and spent much of her adult life working in higher education. Along with Jerome, she served as a parental figure for A.J. away from home. She’d visit him frequently in Columbia, and they’d get meals together. She made an effort to get to know his teammates

“When I lost my wife, it was a real bad time, and A.J. just didn’t know how to take it,” Jerome said. “It hit him hard, man. Because she was a softer side of me.”

In the time since, the relationship between A.J. and Jerome has only grown tighter and more meaningful. There were days when A.J. would come visit Jerome’s house simply to get away. He and Jerome would hardly say a word to each other. They didn’t need to.

Jerome sees himself in A.J. He sees his Anthony in him, too. He sees a boy who evolved into a man. Fittingly, when A.J. packed his bags and was ready to leave Columbia for Canada in late March, Jerome served as his chauffeur. Emotions rushed to the surface the moment Jerome said goodbye.

“He’s just a good kid, man,” Jerome said. “It really hit me when I took him to the airport — he’s not coming back.”

Im 100% ready pic.twitter.com/b2G8T9g8EW

— AJ Lawson ️ (@ItsAJLawson) April 19, 2021

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies