‘Shoeing horses is a passion.’ Lexington organization honors legacy of Black farriers.

In the racing industry, the trainers, breeders and jockeys often get lots of attention, but on Saturday, a Lexington organization dedicated to telling the stories of Black horsemen shone a spotlight on the farriers.

“A horse is just as good as his feet are,” said Bill Cooke, vice president of Phoenix Rising Lex and retired museum director at the Kentucky Horse Park. “Historically, farriers served as veterinarians before there were veterinarians.”

Since 2016, Phoenix Rising Lex has been holding awards ceremonies celebrating Black jockeys, trainers, owners, grooms and exercisers. This year’s ceremony, held Saturday at the Charles Young Center, was all about the blacksmiths.

“We just kind of forgot them,” Cooke said. “This year, we decided it was time to rectify that situation.”

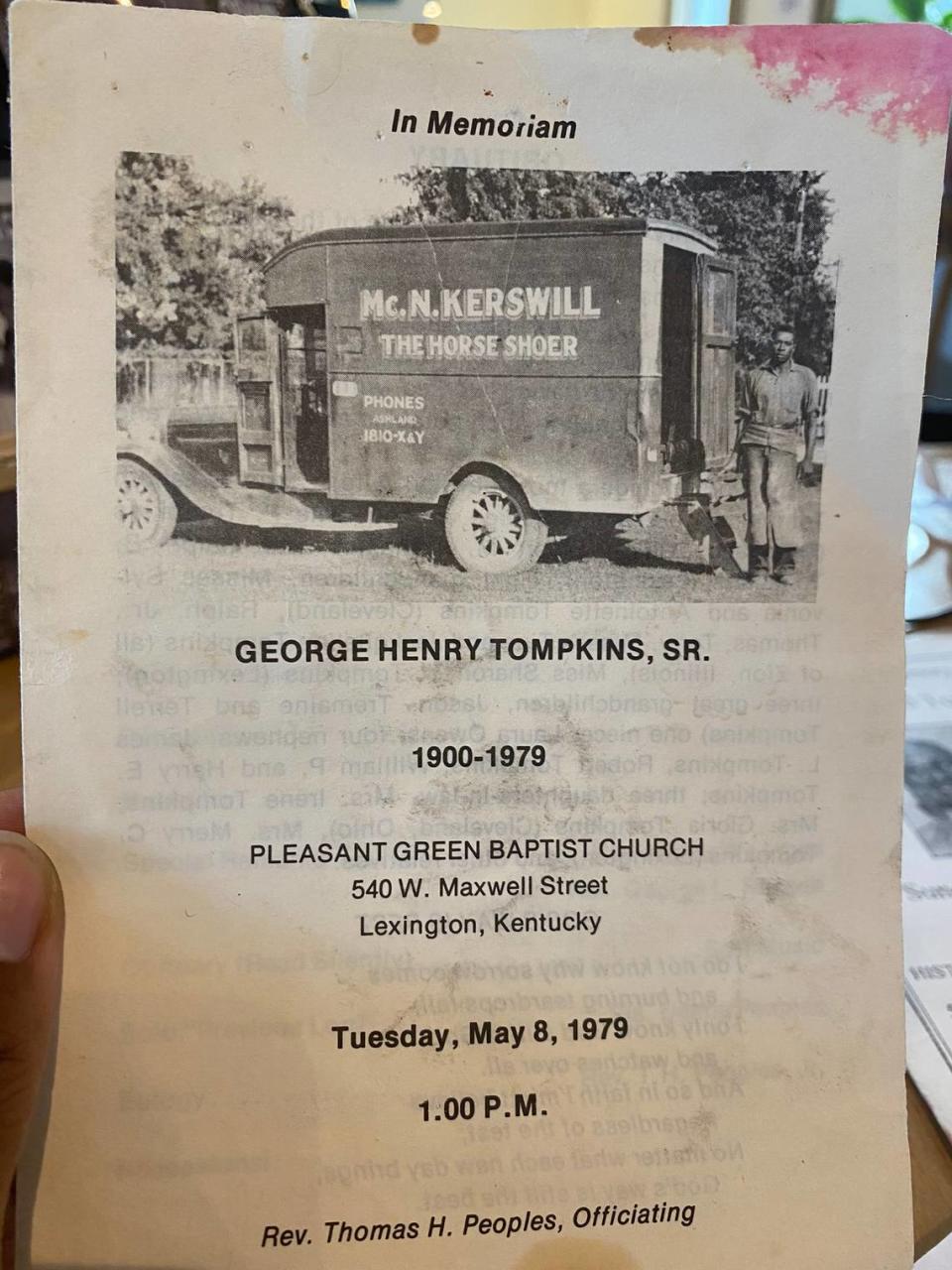

Tina Tompkins’ grandfather, George Tompkins, was born in 1900 and went on to become a farrier who shod racing greats including Man o’ War. She said old ledgers indicate that her grandfather earned about 50 cents for that.

She said George Tompkins gained a reputation as one of the world’s best blacksmiths and flew to Europe to shoe horses.

“He was a good family man,” Tina Tompkins said. “From his success, he would take care of the neighborhood. He was generous and giving.”

He also took on apprentices including Jackie Thompson, who shod a number of Kentucky Derby winners, and his own son, Ralph Tompkins.

Tina Tompkins said her father, Ralph, was the youngest of George Tompkins’ sons, and the family pooled their money to send him to college to become a teacher. Instead, she said her dad came home and decided to become a farrier like his father.

George Tompkins, who died in 1979, was later inducted into the International Horseshoeing Hall of Fame, which was established in 1992.

Tompkins said she told her daughters, who were with her Saturday, that their great-grandfather was there with them.

“He’s here in me. He’s here in you. And he’s here in spirit,” she said she told them. “I’m sure he’s just smiling down and saying ‘thank you.’”

Historian Yvonne Giles said she was surprised to learn that there is a long and rich history of African-American farriers in Kentucky, and there is a wealth of information out there to be gleaned.

Giles said writings by W.E.B. DuBois indicate that there were 512 African-American blacksmiths living in Kentucky at the time of the 1880 census.

“I was just totally floored when I started working on this,” she said.

The earliest reference she found to African-American blacksmiths in Lexington comes from Rolley Blue, who in 1818 advertised his blacksmith shop on Water Street as offering iron work and horse shoeing “done at the shortest notice.”

“They knew that their work was important and vital to the racing industry,” Giles said, referencing Lynn S. Renau, who wrote in “Jockeys, Belles and Bluegrass Kings” that “an inept farrier can ‘nail a horse to the ground’” while “a good one can give him wings.”

Duane Raglin, who has been shoeing horses for nearly 30 years and now runs Raglin Farrier Service, was honored by Phoenix Rising as part of the current generation of farriers.

Raglin said the celebration Saturday was meaningful to him because “no one talks about the guys that are staying after hours ... sore feet, sore back.”

Shoeing horses, he said, is a competitive, demanding and sometimes dangerous job.

“Every day could be your last,” he said.

But he said he’s more comfortable working on a horse than anywhere else.

“They are like humans, with multiple different personalities,” Raglin said. “You always get more done finessing them. You’re not going to overpower them. So talk sweet.”

Raglin gave thanks to “everybody that was before me that gave me the instruments to use.”

“I take pride in the fact that guys before me were in the hall of fame,” he said.

Raglin, who grew up in the Zion Hill community near Midway, spent five years working as an apprentice with John Collins and worked with Collins five more years afterward before going out on his own.

His father, Rev. Earl Brooks Raglin, worked as a groom early in his career. Now, Duane Raglin’s son, Hunter, who works with him, is the third generation of his family to work in the horse industry.

Raglin said they shoe horses for six farms, as well as about 20 track horses. They also work with in partnership with Park Equine Hospital, he said, adding that even after years in the business, “I’m still learning.”

He said his job is to “make sure everything is hitting the ground as smooth as possible at 35, 38 miles per hour.”

Often, he said, that begins with assessing a foal and working to straighten out problems caused by “limb deformities, limbs going the wrong way.”

“I’ve had horses sell for nothing at Keeneland, no bid, and I’ve had horses go for $2 million,” he said.

“Basically, you live for the horse. You get your vacation when you can get it,” Raglin said. “If you don’t love it, you won’t last. Shoeing horses is a passion.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies