She is 8 years old. I ask her what the war in Ukraine is like. 'Terrible,' she says.

Eight-year-old Sofia sits beside me, in a park in Irpin, a suburb of Kyiv, next door to Bucha, in a now placid neighborhood where this year Russian soldiers massacred hundreds of civilians.

I’ve asked Sofia what the war was like for her before she and her family, like so many families in Iripin and Bucha, fled.

“Terrible,” she says, making a small, sour face. Then, as I wait for more, she repeats it, “Terrible.”

I want to know more, and I know, as a psychiatrist who has worked with children during and after wars for 30 years, that words about terrifying experiences don’t come easily. “Would you draw ‘terrible’ for me?” I ask, sharing a piece of paper and crayons.

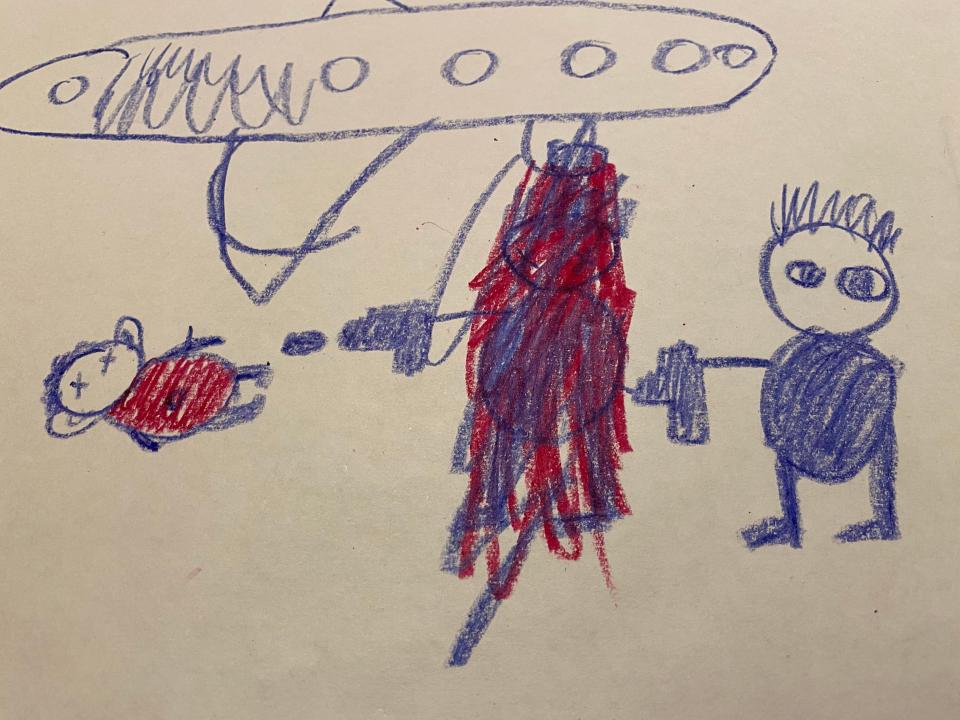

Sofia's drawing haunts me

Sofia bends to the task. She draws a small, child-size body, eyes closed, covered in the red of blood, lying on the ground. Next, a vertical figure standing over the body, holding an automatic weapon. “This,” she tells me, “is the Russian soldier who killed the girl.” Behind him rises a third figure, a Ukrainian soldier, who, she says, with some satisfaction, shoots the Russian.

Opinions in your inbox: Get exclusive access to our columnists and the best of our columns every day

We sit together silently, contemplating the murder and revenge Sofia has summoned up. It’s a lovely day, with chestnut blossoms filling the limbs of tall trees, perfuming the air.

Sofia picks up another crayon, draws a plane flying low above the figures. Suddenly, she scribbles a burst of red on the Russian soldier. “Now, I believe he’s really dead,” she says in a voice that is as uncertain as it is hopeful.

Sofia’s drawing haunts me as I listen to other children. They have heard that Russian soldiers have killed children, and, like Sofia, they fear that nothing, not even brave Ukrainian soldiers, will permanently remove this alien menace.

I recently visited Ukraine to help children and their families devastated by the Russian invasion and to take steps with my Ukrainian partners to create a nationwide program to heal the trauma that affects millions of Ukrainians so profoundly. The terrible memories of death and destruction and fear of the future persist even when children like Sofia are out of harm’s way.

Though 7-year-old Oleksandr was in Lviv, on his way from intense fighting in the eastern city of Pavlograd to safety in Poland, he gave the central place in his drawing to the grave of a murdered cousin. His mother told me he is “normal” during the day, but screams in his sleep.

U.S. must investigate: Was Palestinian American journalist killed by Israeli soldiers?

Millions of children suffer trauma in Ukraine

Since the war began five months ago, millions of Ukrainian children have been traumatized by a world that has become darkly incomprehensible and overwhelming – for the 60% who have had to leave their homes, as well as those who are living close to the front lines.

It’s not individual treatment that the vast majority need, but rather a national program of public health education, a nonstigmatizing, skill-building approach that recognizes that their psychological distress is a reasonable and remediable response to a catastrophic situation.

Angelina Kasyanova, a 19-year-old university student and hotline volunteer whose home in Irpin was scarred by artillery and bullets, understands this. When I explained the program of population-wide trauma healing, of self-care and group support that my Center for Mind-Body Medicine colleagues and I are sharing with Ukrainian physicians, mental health professionals, clergy, teachers, military and youth peer counselors, she got it.

“Yes,” she said, “you will teach us to use these techniques to help ourselves, and then we will teach them to others.”

As we sat at a picnic table outside her home, I did teach a couple of these techniques to Angelina. Together, we breathe slowly and deeply to stimulate, as I explained to her, the vagus nerve, which will quiet the fight-or-flight response, which, when it continues over time, can make sleep and concentration challenging, and provoke children to irritability and hypervigilant anticipation of future threats.

Kids – even self-conscious teenagers like Angelina – are natural experimenters, and she felt good, satisfied that 10 minutes of slow, deep breathing quieted her body, and hopeful that over time, it can calm the fear and anger centered in the portion of her emotional brain called the amygdala. In a world where children have so little power, controlling how her body feels and reacts is so affirming.

I pitied Russian people: Then came the rage of their war in Ukraine

Angelina and I discussed the severe trauma of children who call on the hotline, who are living close to fighting or under Russian occupation. I explained that these kids are likely experiencing the “freeze” response, a last-ditch mechanism for surviving overwhelming trauma that is meant to be quickly turned on and off.

“Think,” I said to her, “of a captured mouse, limp – frozen – in the jaws of your pet kitty.” I pointed to a gray cat curled on a nearby chair. “If the mouse doesn’t fight, kitty gets bored, and drops her. Frozen Miss Mousey shakes herself off and runs back to her mouse hole.” The freeze response has come, done its job, and gone.

Individual transformation and collective healing

In the fearful, flat-voiced children who call the hotline, it is likely that the freeze response persists. Their bodies may be limp or rigid, and their brains pour out endorphins to blunt emotional as well as physical pain. They may remain socially withdrawn, even long after the threat is over.

Nowhere to turn: Families are overwhelmed as kids' mental health needs go unmet

When I asked if Angelina would like to learn Miss Mousey’s technique for relieving the freeze response, she looked skeptical, but nodded yes.

I put on fast, driving, electronic music, and she and I stood, shook our bodies, from our feet up through our chest and shoulders and head. We did this for five minutes, as her father, a long-haul truck driver, smiled and shook along with us. We paused and relaxed for two minutes of awareness, and then, as I played Bob Marley’s “Three Little Birds,” we let ourselves move freely.

Afterward, Angelina was, like the vast majority of kids and adults with whom I’ve done this, both calmer and more energized. She felt “friendlier” and “light hearted.”

Now, Angelina wanted to show me around. She pointed to a pile of shrapnel from the anti-personnel weapons that had burst near her house, showed me the bullet holes in a neighbor’s car, and invited me on a tour of the basement bomb shelter to which her family retreated nightly. Mattresses cover the floor, with pennants of favorite European football (soccer) teams strung above them. She pointed with pride to a corner mattress covered by a bright blanket, “That’s my bed.”

Many people ask me if the children of Ukraine will ever get over their trauma. “Yes,” I say, “Just about all of them,” recalling young ones from Kosovo and Gaza who’ve lost parents and homes.

Ukraine war diary: 'I would never imagine this and I will never forgive Russia.'

Over 30 years, I’ve seen them begin with slow, deep breathing and shaking and dancing, and go on to use imaginative techniques like drawings, journals and guided imagery to look at their daunting situation in new, more hopeful ways.

In the small groups our trainees learn to lead, the kids feel a supportive connection to others who’ve gone through the same kind of hell; 80% of kids who begin these groups qualifying for the diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder no longer qualify at the end of 10 or 12 sessions, and the gains hold.

Abortion extremists undermine cause: Medical students shunned a doctor because of her abortion views

I believe that in Ukraine, even more is possible. As kids come into physiological and psychological balance, and mobilize their imagination to deal with persistent difficulties, many will discover untapped reservoirs of compassion – and a desire to share what has helped them with others who are also suffering.

This kind of psychological growth and transformation after trauma is well-known to Indigenous people, and has been rediscovered by modern psychologists, who call it “posttraumatic growth.”

I see the seeds of it in Angelina’s hotline counseling, in Sofia’s generous sharing, and in Anastasia, Oleksandr’s 13-year-old sister, who misses her old home terribly, and relives the terrors of nearby explosions, but finds peace and purpose in tending to Oleksandr and their younger brothers.

It is this process of individual transformation and collective healing that the 3,000 my colleagues and I hope to train will be able to bring to all of Ukraine’s children.

Dr. James S. Gordon, a psychiatrist, is the author of "Transforming Trauma: The Path to Hope and Healing," a clinical professor at Georgetown School of Medicine, and the founder and CEO of The Center for Mind-Body Medicine.

You can read diverse opinions from our Board of Contributors and other writers on the Opinion front page, on Twitter @usatodayopinion and in our daily Opinion newsletter. To respond to a column, submit a comment to letters@usatoday.com.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: War in Ukraine: Children bear emotional scars of Russian conflict

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies