‘I remember every single second of those 43 years’: A conversation with Kevin Strickland

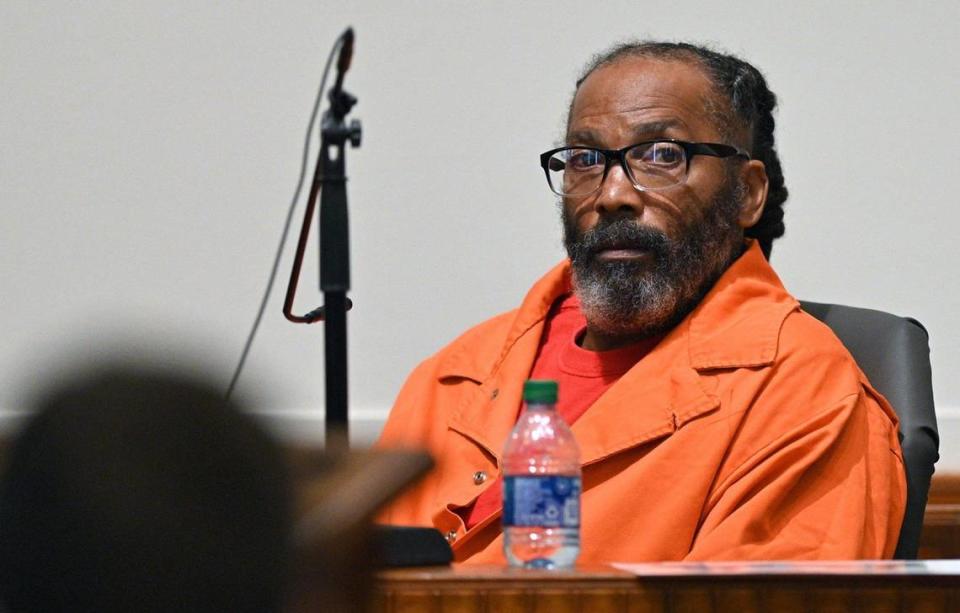

A week ago Tuesday, Kevin Strickland was released from prison after serving 43 years for a triple murder he did not commit. By Thursday, every major media outlet in the country had covered his story. By Friday, he was a millionaire, the beneficiary of an online fundraising campaign created by the Midwest Innocence Project, the Kansas City-based legal nonprofit that worked for years to overturn Strickland’s conviction.

On Saturday afternoon, in an interview with The Star in the second-floor offices of the Midwest Innocence Project, Strickland spoke carefully and with detectable reluctance about the almost unfathomable reversal of fortune he’d experienced over the previous 96 hours. If he was ever a man that was comfortable discussing his feelings, that changed the day an all-white Kansas City jury sentenced him to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 50 years.

They don’t call those a “hard 50” for nothing. Strickland is stony, smile-averse, emotionally coarsened. He expressed polite appreciation for the fanfare that has surrounded his release but hasn’t much been in the mood to celebrate. His first meal as a free man? “Some fish thing my attorney recommended at dinner,” Strickland said. “I don’t know them fancy fish names. I participated because I was the, what would you call it? Guest of honor type of deal.”

He didn’t seem particularly dazzled by the money, either. The GoFundMe donations — the amount had climbed to $1.6 million as of Tuesday morning — will provide Strickland with considerable long-term financial stability. But whatever peace of mind that gives him is diluted by an umbrage at a criminal justice system that made a fundraiser necessary in the first place.

“I’ve heard about it, it’s nice, I appreciate it. But it’s a shame I have to resort to that,” Strickland said, a reference to the fact that, under Missouri law, he isn’t eligible for a dime of compensation from the state that snatched away four decades of his life.

The conversation was a cold reminder that, despite the positive outcomes of the past week, Strickland’s story is a tragedy. The man served one of the longest wrongful convictions in U.S. history. His life was stolen from him. There isn’t a happy ending to a story like that. And Strickland isn’t interested in pretending otherwise.

Q: What have you noticed that surprised you since your release on Tuesday?

A: That everybody might not be as hateful as the stuff I’ve been seeing in the media over the years: mass murderers and blowing up buildings and people shooting up the supermarket. Not everybody is in that lane. The couple places I’ve been, people reach in their pockets and give me five dollars, ten dollars, whatever they have. That tells me there’s a lot of love and good people out there.

Is that the impression you got from the media? That the world had become this rotten place?

Yes. It gave me the sense of, I wanted out of jail but I’m not sure I want to go.

How’s it been interacting with people on the outside? Do you find yourself wanting to be around others, or wanting to be alone?

I feel like I have to work on reacquainting myself with my family relationships, and I have my legal counsel and social workers who are trying to help me get acclimated to society. But the sooner I can get somewhere by myself and my animals that I wish to have, the better.

Animals?

Yeah. I’m a dog person. Dogs and cats. Lizards and snakes.

You want to get some pets.

Pets, yes, but food too. Chickens is food.

Do you think you’ll stay in Kansas City?

I don’t know what my financial situation is going to be. I trust I will get the (GoFundMe) donations. But I don’t really want much. I want some peace. I want to go where I want to go when I want to go. I want a roof over my head and bills paid. And to be able to turn up the music as loud as I want.

Sounds like you want a farm, for those chickens?

Now you’re coming around. You’re getting closer. But you’re not getting my address.

One of the first things you did after being released was visit your mom’s grave site.

That was, uh, yeah. That was something. Looking at that dirt like that, knowing I won’t ever be able to look her in her eyes and talk to her and tell her, “See, mom.” Which — I knew in her heart she knew I didn’t do it. But in all those years she never put that question to me, straight to me. Because she was gonna believe her son. That’s what mothers do. It was really emotional. That’s my mom. She’s gone.

She died in August. You might have been able to see her before she passed had the Missouri Attorney General’s office not fought against your release and used various legal maneuvers to delay the process. Do you feel that the attorney general, Eric Schmitt, robbed you of that?

Yes, certainly. They made the maneuvers they made to let my mother pass before I could get to her.

How’d that make you feel?

Feelings is — that’s like an emotional thing. I didn’t really feel much about it. I just looked at it as something they had to do as part of their job. I felt there was going to be resistance, and I was just trying to calculate how long it would hold up.

Where in Kansas City did you grow up?

55th and Jackson is where we moved after fourth grade. Back in the early ’60s and up to the ’70s, “out south” in Kansas City was considered anything past 31st and Troost. If you moved past that, you were kinda uppity. It represented that you had a little money. They still had colored water fountains downtown where you had to get your water outside. When we were able to move to 55th and Jackson in 1969, it was like they played “The Jeffersons” song, “Movin’ On Up” — that’s what I thought in my mind. The school was better, and other Black folks started moving out there. And the white folks started packing up and moving further out south. I witnessed all that.

I went to grade school at JS Chick, between Norton and Jackson on 53rd Street. I did well in school. I paid attention. The teacher would teach us multiplication, and I’d get it in a day, and I’m waiting for everyone else to catch up. And that got me in trouble. Because I’m clownin’ while I’m waiting for the rest of the class to get it. Bothering people, being mischievous, telling bad jokes — as my legal counsel will tell you, I still do. But yeah, I did well through school. I was in a two-parent home, and that was a big deal then too. We didn’t come up in poverty. I can’t say I remember us ever getting government assistance. Mom and Dad provided well for the house, considering they had five kids.

What’d your dad do for a living?

He was a chef. Food service. [Pauses] Am I writing a book here, why am I talking about this?

Just curious!

I’m not gonna give all this up. This could be a book forthcoming. I gotta figure out a way to generate some finances. Back up, buddy.

Can you talk about some of the things you thought about while in prison, memories you cherished?

I’m a sports person, an outdoors person. I thought about that. I used to go hunting and fishing and horseback riding. I played church league fast-pitch ball. I wish they had camcorders at that time to record my playing. I think I was probably the only person at that age that ever had 200 at-bats and never struck out one time. Lead-off man, home-run man: I could do it all.

Over time, did you find it harder to access those memories? Did you feel you had to work to keep them from slipping away?

You keep throwing that word “feel” in there.

You don’t like that.

I had to check my feelings at the door when I walked into the penitentiary. You had emotional moments in prison, yes. People pass. I’d get an obituary in the mail of a family member. I would look at it and fold it up and put it in a locker and go along and finish what I was doing. The pain of losing someone very dear to me under circumstances where I can’t visit them ... I can’t say I held them (feelings) back. I just couldn’t release them. They wouldn’t come because of the environment I was in.

Do you feel that’s part of your purpose now that you’re free, to try to feel again?

Yes.

Do you know how you’ll try to do that?

Well... uh.. communication. Learning about people, learning about myself. I know what I want. I want love. Not relationship love. But family love, friendly love.

So far, does it seem like it will be hard to get back in touch with your emotions?

I certainly know it will be. It is, right now. Just in these past, what, five days.

Have you had any time since Tuesday to reflect on the fact that you’re actually free?

Some people tell me I think too deep. I overthink.

How so?

I want everything in a day. And that ain’t the way it is. My mind is moving like I want to make up time that I can never catch up with again.

What do you remember about the day you were arrested?

Police came to my house. And they asked me would I be willing to come down and answer some questions. I asked if I had a choice and they said no. Wasn’t no rights read, wasn’t no handcuffs placed on me. I was placed in the backseat of a car. I’m pretty sure it was a detective car as opposed to a squad car. And I hadn’t done anything wrong. So I had no problem complying with their questions. And I engaged them in free conversation en route to the police station and while at the police station. I didn’t try to hide anything. I hadn’t done anything.

You were then charged with the murder of three people in a Kansas City apartment and eventually convicted after a mistrial. Two other men, Vincent Bell and Kilm Adkins, were also charged for the crime. After you were convicted, they pled guilty and told police that you had nothing to do with the murders. Were you aware of that at the time?

I learned that — I was convicted in April 1979 and transferred to the penitentiary in Jefferson City on July 9. I heard Bell pled guilty in August, and I received a copy of his transcript in September saying I wasn’t involved.

So you learned very quickly this information that seemed like it should set in motion your release from prison. What did you do then?

I bought stamps and was writing letters before I even left the county jail: “Somebody help me.” “I didn’t do this.” My mother and father would send stamps in the mail for me to do what I needed to do. I wrote letters to people in the country, out the country, whoever. Any lawyer’s name I saw on the TV — auto or insurance attorney, whoever. If it said they were attorneys, I would write to them.

Was anybody helping you? Were you doing all this yourself?

Nothing other than my family providing me with stamps. I was out there on my own. That’s all I had.

How discouraging was it to send off all these letters and get nothing back for years and years? Did you fall into funks? Were there periods during which you stopped trying?

No. Next letter.

How did your concept of time change while you were in prison? Did it sometimes feel like a year passed by in a month, or that a month felt like a year?

I remember every single second of those 43 years. I didn’t go a year and say, huh, that flew by. Those were slow seconds.

You were offered a plea deal back in 1979. You could have pled down and served about 10 years like the others who were charged in the case. Why didn’t you take it?

That was never a question. I would have had to lie to do that.

Was it hard to convince your family and friends that you were doing the right thing?

It was. But I was willing to die for the truth.

How do you think race played into what happened to you?

I do think race played a part. The fact that I was a young, smartmouth Black teenager, being judged by a jury of middle class or upper class white folks who knew nothing about the type of lifestyle I was living, or even cared. My situation was supposed to be straightened out within 48 hours of me being taken down to the police station. And there I was 7-8 months later facing the death penalty in front of nothing but white people.

How’d that feel?

Scared to death. Scared to death.

How did the prison experience change during the four decades you were locked up?

Well, they moved me all around the state. I was in the Missouri State Penitentiary in Jefferson City three times, Potosi two times, Cameron two times, Western Missouri Correctional Center one time.

Jefferson City, that prison was built in the 1800s if I’m not mistaken. The plumbing — the water came out brown. It didn’t have air conditioning. When they started building these “correctional centers,” they were cleaner and more sanitary. Water wasn’t brown, no vermin. You didn’t wake up in the middle of the night with a rat eating your cakes.

The type of people you lived with, the convicted felons that were coming in — that changed, too. I watched that transition.

Can you talk about that?

Well, once again — I’m thinking “book.”

How about just generally? Did you see the newer convicts as colder, more hardened?

It’s a combination. They were cold hard cowards. Immature, overgrown, adolescent, grown-men children. They were soft. And if you don’t know what soft means — you could put me in the hole, and all I’ll tell you is to bring me my trays and my meal and get the hell on with it. I could sit in the middle of the floor, Gandhi style. I don’t need to talk to you. In the penitentiary, they were men. But the soft generation that started coming in around 1983, they were children. They acted like children.

Cynthia Douglas is the woman who identified you as being at the scene of the crime. She’s the reason you were convicted. Years later, she tried to recant her story, saying she was wrong to identify you at the crime scene. [Douglas died in 2015.] What are your thoughts on Cynthia Douglas?

What she did initially, I didn’t understand it when I was 18, 19, 20 years old. But I knew from family members, reliable sources, that she had expressed that the police made her do what she did. She was under a great deal of pressure. It could have been inferred that she had something to do with the crime, and that if she didn’t cooperate with [the police’s] plan they could involve her in it. I mean, I heard a lot of different versions and theories.

But when she finally came forward and said what she said because of her conscience, that felt good. Because that meant this stuff was about to come out.

Was there a moment when you felt a turn — that you began to feel you might have a real chance at exoneration?

When I acquired legal counsel. I knew all along that all I needed was legal representation. The case was so weak against me that if any attorneys and judges had a chance and the time to look at the actual evidence, I felt they would clearly see who were the perpetrators of this crime. And that I had nothing to do with it. Like I had been saying from the start.

But yeah, my legal team, when I first heard that voice on the phone from the [Midwest Innocence Project] attorney, I think I might have went out and told a few people in the penitentiary that I might have the help I’d been needing for over 30 years.

Do you have any thoughts about reforming the criminal justice system, as it pertains to cases like yours or others?

One of the first things I would suggest is that there be a public defender’s desk in every police precinct across the United States to discourage police from doing things they shouldn’t be doing. So that police can’t encourage victims to identify people who shouldn’t be identified as perpetrators — people who are innocent. I believe the presence of a public defender could knock down actions that people don’t want to believe police do, but that they do.

What about the law that prevented you from receiving compensation for the state? Do you think that’s the way things ought to work, that you have to rely on the kindness of the public for financial support after you’re freed from a wrongful imprisonment?

There’s quite a few other states around the United States that don’t think so.

What now? What are your priorities?

Finding somewhere I can live, where I can be alone and at the same time make arrangements to try to unite my family — the ones I can identify, at least. I want to know who I’m related to. I got family in Florida, California, Michigan. Everybody’s running around and don’t nobody know nobody. I’d like to spend my final days trying to get everybody together and have a big family get-together where we all get together and see who’s who.

This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies