'Really been a struggle': Bill to protect pregnant workers passes in House. Female lawmakers say it's crucial

WASHINGTON – Rep. Jaime Herrera Beutler, R-Wash., told USA TODAY she went into labor with her first child years ago when she was running from a House office building to the U.S. Capitol to cast votes.

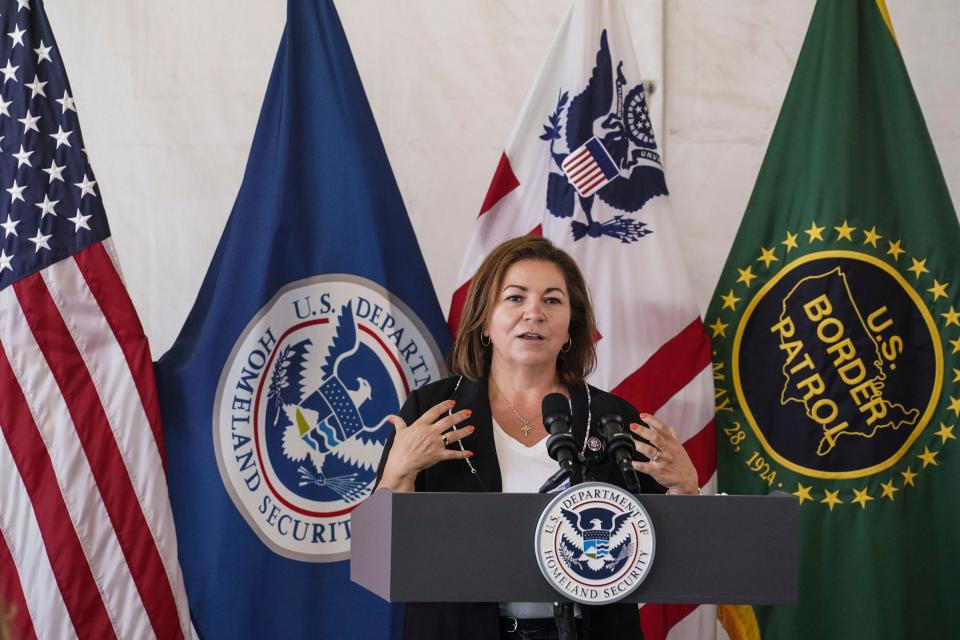

Rep. Linda Sánchez, D-Calif., during her pregnancy in 2009, developed gestational diabetes, a complication only 2%-10% of women develop, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Both women belong to a group of just 10 women in history to have served as a U.S. lawmaker while pregnant.

Such developments could have been much riskier for both of them and their babies if they had been working a job that's more physically demanding or not as flexible, like the waitressing one Sánchez had before she went to college, she told USA TODAY.

And while Capitol Hill has at times lacked accommodations for women — for example, the first lactation spaces weren't installed until nearly 2010 — Sánchez said, "Being a member, I had a certain degree of flexibility that I think most women, and most, in most workforces in the country, do not."

Sánchez and Herrera Beutler are part of a bipartisan group of lawmakers who find current anti-discrimination laws don't go far enough to address the needs of employees who are expecting. It's why they're pushing for passage of the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, which would require employers to provide specific accommodations for pregnant employees.

Pregnant women — whether they are walking the halls of the Capitol, working on the front lines, or in restaurants and offices — still face discrimination more than 40 years after legislation was passed to prohibit it. According to the House Committee on Education and Labor's research, 62% of employees have witnessed such discrimination in their workplaces.

The legislation passed the House on Friday with a bipartisan vote of 315-101.

Though many of the interviews USA TODAY did with lawmakers focused on the legislation as being a step toward addressing pregnancy discrimination as largely a women's issue, it is important to note that lack of accommodations toward people carrying children can occur to those who do not identify as women.

What would the PWFA do?

The new legislation would extend protections beyond those provided by the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, a decades-old law that prohibits sex discrimination on the basis of pregnancy in a workplace, including any aspect of employment such as hiring, firing, pay and job duties.

Congress enacted the PDA in 1978, in response to Supreme Court rulings that found pregnancy discrimination was not a form of gender discrimination. This made it hard for women to pursue legal action against their employers if they were wrongfully fired or mistreated.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act has made it so women can continue working into their pregnancies, but advocates say now it doesn't go far enough to protect the health of the mother in the workplace or bar her from being fired for requesting those accommodations, among other discriminatory practices.

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act would require employers to provide reasonable accommodations to their employees, and track the requests similarly to the Americans with Disabilities Act, per a summary of the legislation. Under the PWFA, employers with more than 15 workers would have to make reasonable accommodations to employees and it would be unlawful for employers to deny such requests for the "known limitations related to the pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions of a qualified employee."

Some of these accommodations include additional breaks for eating and to use the restroom, limiting heavy lifting, stools to rest on, and more.

Herrera Beutler, who is an author of the legislation, said providing water or a stool would "allow a woman to both pursue a career interest, while also starting a family." Such accommodations won't put them out of business, she said.

According to research by the Childbirth Connection — an initiative focused on improving pregnancy care — approximately 250,000 pregnant workers are denied accommodation requests each year.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., told USA TODAY constituents regularly call her office "to talk about the problems they faced when an employer insisted that they meet physical demands that just weren't possible during pregnancy."

Though the accommodations may seem small to some, Rep. Cindy Axne, D-Iowa – who worked in human resources when she was pregnant and before she worked in government — said she saw firsthand how places of employment may not give accommodations to those who need it.

"I can tell you by the time women even get to the workplace, when they're pregnant, they're worn out," Axne, the mother of two boys, told USA TODAY. "I honestly don't remember one person getting up for me on a train. ... So by the time you finally get to work, you need accommodations to make sure you can get the job done."

Accommodations critical to healthy pregnancy

According to Kathryn Luchok, a research professor in the Department of Anthropology and a senior instructor in the Women’s and Gender Studies Program at the University of South Carolina, such accommodations are critical to preserving a healthy pregnancy.

"For instance, standing for long periods, like you have to do if you're at the checkout counter or on an assembly line, is not recommended, particularly as you get more advanced, because it's linked to premature labor," she said.

"You know, in some workplaces, that's not a big deal at all, but in other workplaces, that's a real issue," Luchok told USA TODAY.

Sánchez agreed, saying, "Other women might not be as fortunate" as she was when her feet swelled up so badly that she opted to wear flip-flops on the House floor. Even though they are technically against the chamber's dress code, no one said anything.

"Let's say you were a warehouse worker and had to wear closed-toe shoes, your employer's not gonna let you put on flip flops," she continued. "In the broader scope, this bill is really important because it's gonna give pregnant workers the opportunity to ask for simple accommodations for them so that they can have healthy pregnancies."

Axne pointed out that many jobs women take involve standing.

"Whether they're a caretaker or a waitress, they're working in a nursing home, whatever, they're on their feet, all day long, teachers, nurses, all of these folks, these are typical women's professions," she said. "It really is a medical issue that's so necessary for women. And it's time we start looking at it like that."

People of color face more discrimination

Pregnant people of color face the issue more regularly, according to an analysis from the National Partnership for Women and Families, which found that from 2011 to 2015, Black women filed nearly 29% of pregnancy discrimination charges to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Luchok explained "intersectionality" is an issue as these women are more likely to face gender, race and class discrimination.

Often, these women are afraid to ask for accommodations out of fear of retaliation from employers. "The more marginalized you are in society," she explained, "the more likely you're going to put up and shut up."

Sánchez, a member of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, noted women of color are four times more likely to die in childbirth and said it's "because they're not given those kinds of accommodations or often because they work in workplaces where they have to do physically demanding labor while they're pregnant."

According to the National Women's Law Center, Latina, Native-American, and Black women are "overrepresented in low-paid jobs."

Black women make up nearly 10% of the low-paid workforce and Latinas make up 16%, according to the study.

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act is the needed federal policy solution to respond to their needs, according to Sara Alcid, senior campaign director for Pay Equity and Economic Justice at MomsRising, a national organization focused on economic security for women and families.

"Due to the myriad of ways that racism, sexism and xenophobia work in tandem at the structural level in our nation to curb the educational and career opportunities available to women of color, they are overrepresented in low-paying and physically demanding jobs," she said. "It is in these more physically demanding jobs, at manufacturing and food processing plants, for example, that reasonable accommodations are so key to maintaining a safe environment for pregnant workers."

And while a majority of states and the District of Columbia have already passed laws similar to the PWFA, Alcid said, "There are still so many workers not covered. We need a uniform, federal standard."

The coronavirus pandemic also posed higher risks for women: According to the CDC, pregnant women who contract the virus require intensive care compared to women who aren't pregnant, and are also more likely to be placed on a ventilator.

"At this time, where the economic fallout from the pandemic has been nothing short of catastrophic for women, it is the perfect timing to start working on these systemic problems that have created barriers to success for women, being able to provide for their families and continue to work," Assistant Speaker of the House Rep. Katherine Clark, D-Mass., told USA TODAY.

The legislation has passed the House. What about the Senate?

The Pregnant Workers Fairness Act passed on a bipartisan vote last year in the 116th Congress, 329-73, but was never voted on in the Senate.

This year, a group of bipartisan senators have already introduced the legislation in the Senate, with Republican Sens. Shelly Moore Capito of West Virginia, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska joining Democratic Sens. Bob Casey of Pennsylvania, Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire and Tina Smith of Minnesota as original cosponsors.

“The astonishing truth is that many women are still denied the basic, commonsense accommodations they need at work to ensure a healthy pregnancy and a healthy baby,” said Murkowski in a statement. “This is not acceptable. No employee should have to choose between keeping a job and their health or the health of their baby — it’s as simple as that.”

Though there is bipartisan support, the bill would need to clear a 60-vote threshold to overcome a legislative hurdle called the filibuster to get it to a final vote.

The White House released on May 11 a statement of support for the legislation, saying, "No worker should be forced to choose between a paycheck and a healthy pregnancy."

The bill does have opponents.

Rep. Virginia Foxx, R-N.C., told USA TODAY in a statement she would not support the PWFA due to a lack of provisions to protect religious organizations if a pregnant woman were to use the accommodations to acquire an abortion or became pregnant out of wedlock.

Foxx, the top Republican on the Education and Labor Committee, said, “Our job in the People’s House is not to defy the Constitution, but to uphold it. Employers shouldn’t have to choose between abiding by the law and adhering to their religious beliefs.”

However most of the female lawmakers USA TODAY spoke with emphasized protecting mothers should be a nonpartisan issue.

"If we're gonna recommend people be pro-life, then we need to make sure that those policies aren't just about abortion," said Herrera Buetler, a conservative who is pro-life. "It goes into making sure that there's a whole system that we're encouraging that allows women to live out that dream of having a family."

She continued that for many of her older, male colleagues, while generational divides are often present, they may see their children — where often times both the man and wife must now work to support a household — and "understand more to that, maybe their daughter needs to work up until she gives birth like I did with my pregnancies."

Axne said women are saying, "It has really been a struggle for women. So, across the board, women are saying it's about time."

"Probably, if a man had to deal with this, the law would have been written a long time ago," she said. "We've got more women in Congress now, and these things are becoming a big priority because we do represent half this country as women. And we represent all of the country as mothers and community members."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Congresswomen push bipartisan bill to protect pregnant employees

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies