Rapid Covid testing in England may be scaled back over false positives

Senior government officials have raised “urgent” concerns about the mass expansion of rapid coronavirus testing, estimating that as few as 2% to 10% of positive results may be accurate in places with low Covid rates, such as London.

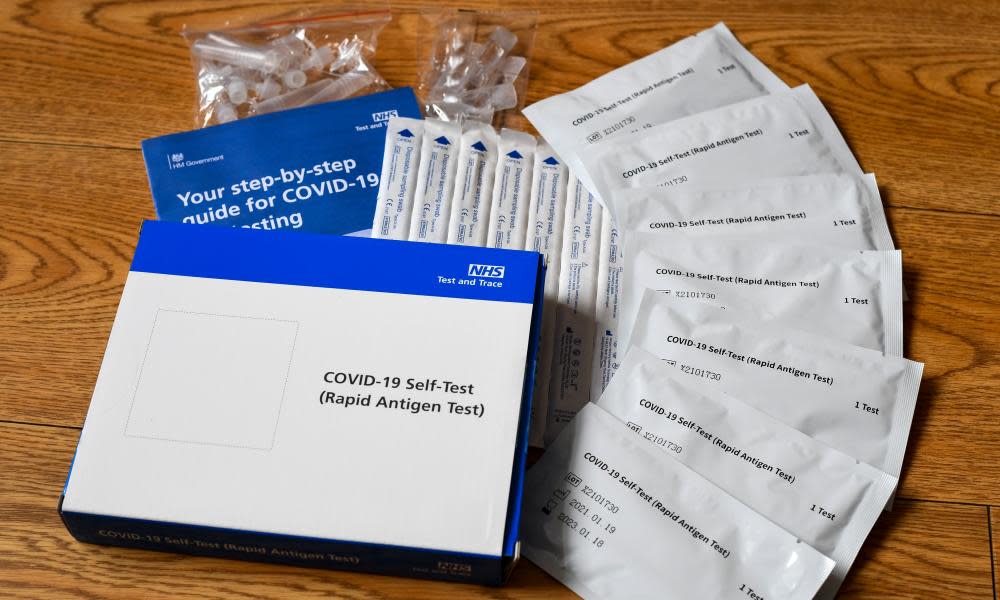

Boris Johnson last week urged everyone in England to take two rapid-turnaround tests a week in the biggest expansion of the multibillion-pound testing programme to date.

However, leaked emails seen by the Guardian show that senior officials are now considering scaling back the widespread testing of people without symptoms, due to a growing number of false positives.

In one email, Ben Dyson, an executive director of strategy at the health department and one of Matt Hancock’s advisers, stressed the “fairly urgent need for decisions” on “the point at which we stop offering asymptomatic testing”.

On 9 April, the day everyone in England was able to order twice-weekly lateral flow device (LFD) tests, Dyson wrote: “As of today, someone who gets a positive LFD result in (say) London has at best a 25% chance of it being a true positive, but if it is a self-reported test potentially as low as 10% (on an optimistic assumption about specificity) or as low as 2% (on a more pessimistic assumption).”

Watch: Could rapid Covid testing help entertainment venues reopen?

Related: What is a lateral flow Covid test and how accurate is it?

He added that the department’s executive committee, which includes Hancock and the NHS test and trace chief, Dido Harding, would soon need to decide whether requiring people to self-isolate before a confirmatory PCR test “ceases to be reasonable” in low infection areas where there is a high likelihood of a positive result being wrong.

The accuracy of rapid coronavirus tests and how they should be deployed have been the focus of months of debate in the UK. The proportion of false positives – people incorrectly told they have the virus – increases when the prevalence of the disease falls. This happens because although the number of true positives is falling, the tests produce roughly the same number of false positives – meaning the proportion of incorrect results becomes greater.

It means thousands of people could be wrongly told to self-isolate and miss out on earnings or education due to inaccurate results. The government has advised anyone who tests positive with a rapid test to take a follow-up PCR test and self-isolate until they receive a negative result – but some experts have said this process is too slow and that a second lateral flow test would be as likely to produce the correct result.

Figures produced by government officials estimate that currently only one in 10 positive results are likely to be accurate in London and south-east and south-west England, where there is less Covid-19 in circulation. In England as a whole, they estimate that only 38% of self-reported tests are thought to be accurate based on the current prevalence of the disease.The Guardian has also learned that Public Health England (PHE) raised concerns about the plan for mass testing, days before it was announced on 5 April.

Prof John Simpson, head of PHE’s public health advice, guidance and expertise pillar, told officials in Hancock’s department that the strategy did not appear to be backed by evidence.

He wrote: “We are a little concerned that this proposal does not provide the evidence needed to justify the extension of testing in the way proposed, does not consider alternative approaches to achieving the over-arching aim (of reducing community transmission) and does not provide a framework for evaluation that would make it possible to determine if the approach actually achieves what it intends.”

Mass testing has been at the centre of the government’s plan to release the UK from lockdown, alongside the vaccination programme. The government has bought millions of the lateral flow tests as part of the £37bn budget for NHS Test and Trace.

The Department of Health and Social Care said that all testing policy was kept under continuous evaluation but that there are “no plans to halt the universal programme”. It added: “With around one in three people not showing symptoms of Covid-19, regular, rapid testing is an essential tool to control the spread of the virus as restrictions ease by picking up cases that would not otherwise have been detected.

“Everyone in England can now access rapid testing twice a week, in line with clinical guidance. Rapid testing detects cases quickly, meaning positive cases can isolate immediately, and figures show that for every 1,000 lateral flow tests carried out, there is fewer than one false positive result.”

Ministers have defended concerns about the accuracy of the Innova lateral flow tests by saying that only one in 1,000 tests will produce a false positive. The government’s enthusiasm for rapid-turnaround tests has divided experts. They are cheaper and quicker than the gold-standard PCR tests and are good at finding the most infectious cases and those that may not otherwise be found – but they are more likely to produce erroneous results.

Watch: What is long COVID?

Data obtained by the BBC from 26m lateral flow tests in March found that, among 30,904 positive results, 82% were correct and 18% were false positives. Coronavirus levels were higher in March and have since fallen, meaning the proportion of false positives will have increased since then, however.

The vast majority of those tests also took place under supervision in schools, where prevalence of the disease was higher last month. The proportion of false positives would be expected to rise as the general population self-administer regular bi-weekly tests at home.

A recent Cochrane review – an analysis of 64 studies – found that rapid tests correctly identify on average 72% of people who are infected with the virus and have symptoms, and 78% within the first week of becoming ill. But in people with no symptoms, that drops to 58%.

Jon Deeks, professor of biostatistics at the University of Birmingham and one of the authors of that review, said the government figures suggested that false positives would outnumber true positives in parts of the country where less than one in 1,000 people have the virus, or 0.1% of the population.

As of last week, according to government figures, England’s prevalence was 0.12% while it was 0.04% in London, 0.02% in the south-east and south-west, and 0.08% in the north-east of England. Deeks said: “When disease is this rare, this is a real waste of resources which could be better used by improving our test, trace and isolate programme.”

Based on the government’s analysis, he said, it would take more than 16,000 tests to find one infected person in London: “If these tests cost £10 each that’s £160,000 to find one person. It shows that this is a complete waste of money at this point.”

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies