The race to the bottom on cutting company tax rates has failed

For the first time in around 40 years something weird is happening to the debate about tax – and it is one that makes calls for ever-lower company tax rates look decidedly out of step.

Since the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, under the thrall of neo-liberalism, cut company tax rates in the UK and US, the mantra on company tax has been to cut and reap the benefits.

The logic goes like this: cut company tax rates; multinational firms come to the country; economy booms.

It’s the type of policy that always worked better in theory than reality.

But cutting taxes is easier for governments to sell as doing something to spur investment than long-term measures such as education or infrastructure.

It also seemed more proactive than acknowledging that when you have a heck of a lot of iron ore in a country with a stable and relatively corruption-free system of government then companies will come regardless of the tax rate.

Twenty years ago Australia’s company tax rate of 34% was slightly above the OECD median rate of 32.5%; now our rate of 30% is one of the highest and well above the 23.5% median rate.

The problem with the tax-cut mantra was that anything one country could do, another could do more so. And they did – producing the inevitable race to the bottom as countries cut company taxes evermore.

Once the rate went below 25% the benefits were negligible, and yet countries kept cutting.

But now the push is going the other way.

The UK Conservative government has just moved to increase their company tax rate from 19% to 25% in April 2023, and US president Joe Biden has pledged to increase the US tax rate from 21% to 28%. That won’t undo all of Donald Trump’s cut from 35% but it is a significant reversal of direction.

The reason for the reversal is the logic no longer works, even in theory.

The Trump tax cuts did not lead to more investment; just companies having greater after-tax profits, and the US government having less revenue.

And in our globally fluid financial system, companies have become experts at shifting profits to locations with lower tax rates, while not shifting production.

So now a change has come.

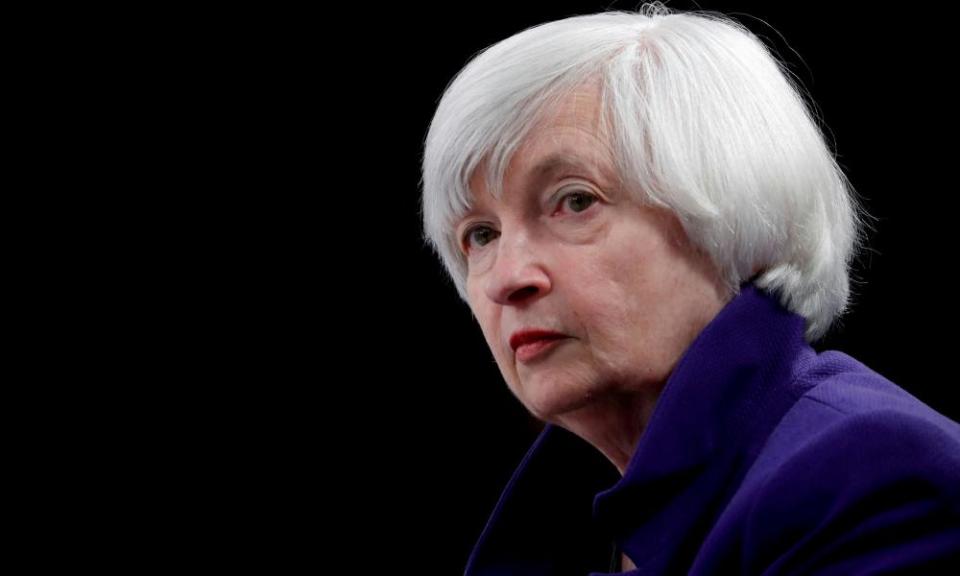

We have US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen leading the push from the OECD for a minimum global company tax rate and new rules to prevent profit shifting.

The move has generally been met with support.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has said that Australia “welcomes” the discussions “to agree a globally consistent approach to the tax challenges posed by the digitalisation of the economy.”

Labor’s Andrew Leigh, who has long been campaigning for greater efforts to prevent multi-national company tax avoidance, told Guardian Australia that with end to the “global race to the bottom in company taxes ... those elements in the Liberal party still pushing for Australia to cut company taxes are looking as old-fashioned as the climate change deniers.”

Leigh cited the OECD’s “Pillar Two” tax proposal which suggested that a global minimum tax rate “could add US$42-70bn to global tax revenues” and that “Australia should be an active participant in these discussions.”

He also notes that “part of ensuring that firms pay their fair share of tax is cracking down on tax havens. Two-fifths of multinational profits now flow through tax havens, which undermine the company tax base of advanced countries like Australia.”

But the problem is not just tax harbours or rates.

The exemptions and deductions in taxation legislation also enable companies to find ways to avoid paying. As the Guardian’s Ben Butler reported this week, Shell expects to pay Australia no resource tax on gas drawn from the Gorgon project.

And the demand for lower taxes is not completely gone. The OECD this week even suggested Australia should reduce the large-business tax rate of 30% to the lower rate of 25% that exists for small-median business in order to remove distortions.

But the race to the bottom has clearly failed, and the sensible policy work is now about undoing the errors of the past 40 years.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies