Pride review – a beautiful rainbow patchwork of queer history in the US

Remember Madeleine Tress? The charismatic lawyer born in Brooklyn in 1932? A cross-dressing lesbian who liked to frequent mafia bars, where “with a Smart cigarette hanging out of my mouth, I passed”, who was investigated by the FBI, and who wrote a memoir about her life and love for her partner of 40 years, Jan? No, me neither. Happily, my head is now crowded with such thrilling, courageous and previously obscure(d) figures thanks to Pride (Disney+), a giant mosaic of a mini-series spanning six decades of LGBTQ+ history in the US. The kind of big-hearted, big-moneyed, inherently American show that would probably be condensed into a single late-night hour on BBC Four if it was covering British queer history.

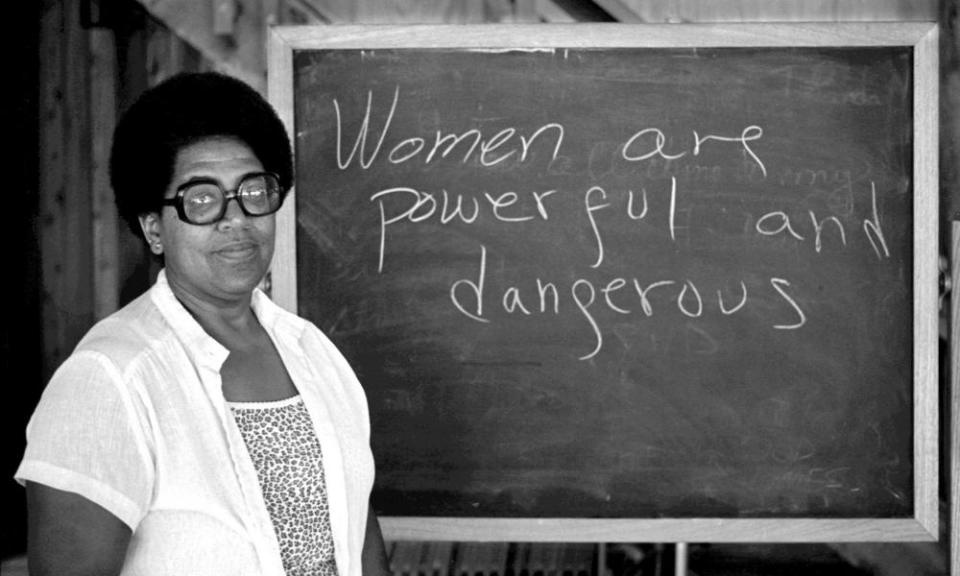

Each episode inhabits a different decade – from the 1950s to the 2000s – and is made by a different queer film-maker. The approaches are various – with mixed, sometimes untidy results, which is precisely what you would expect from a creative patchwork project like this. Andrew Ahn’s film about the 1960s relies mostly on archive footage, which is usually the best part of a historical documentary. Cheryl Dunye’s 1970s episode is a personal love letter to film-maker Barbara Hammer and poet Audre Lorde. The 1980s chapter, directed by Anthony Caronna and Alexander Smith, chronicles the well-documented story of the Aids crisis in New York through lesser-known perspectives: the joyous, intimate home movies of Nelson Sullivan, who spent most of the 80s wandering around downtown with his camcorder and his dog, Blackout. And the life and times of black trans advocate Ceyenne Doroshow, in a touching telling of a history familiar to all of us who fell in love with Pose. Visibility is an overriding theme here. Many films use framing devices (such as Sullivan’s tapes) to reframe familiar queer narratives: a manoeuvre that feels at once radical, overdue, and – to reclaim a loaded word – entirely natural.

The opener, People Had Parties, is directed by Tom Kalin and set in the pre-Stonewall, McCarthy-era 1950s. A time that, as gender theorist Susan Stryker points out, is often reduced to “the deep dark days of the closet”. In fact, as the film proves, “the idea that the closet was nailed shut is historically inaccurate”. Kalin’s film zooms in on the story of Tress, whose father gave her The Well of Loneliness and Psychopathia Sexualis when she was 12. Also Lester Hunt, a Wyoming senator whose son was convicted of soliciting a male undercover officer for sex in Lafayette Park: one of many cases of entrapment in the morally outraged McCarthyite US. A year later, following a sustained homophobic campaign of persecution by politicians set on destroying his career, Hunt killed himself. To this day there has never been a Department of Justice investigation into his death. Both these stories, incidentally, are illuminated through earnest reconstructions by Alia Shawkat and Raymond J Barry. These add nothing, and threaten to detract from the inherent drama of the histories. Then again, I’ve never seen a dramatic reconstruction that didn’t make me cringe.

The archive footage and photos are powerful enough. Kalin’s otherwise conventional documentary is braided with lovely old reels of San Francisco, all trams, streets slick with rain, sailors and everyone in hats. Also beautiful are photos and quivering home movies of dinners, cocktail parties, cruising, all of which shows that queer people in 50s America were, as one contributor puts it, finding ways to be “incredibly bold”. They may not have been out to their friends, families and colleagues but they were visible to one another. One pair of snaps shows two men, hair styled and heads pressed together, posing in a photo booth, displaying their love for one another in private as the public passes by on the other side of the curtain. In the first photo one of the men presses a balled-up hand against the other man’s chest, a gesture “we all recognise”, as the contributor so rightly notes, expressing tension, passion, defiance. In the second photo the men kiss, and the man’s hand is open.

As with the lives it seeks to represent, Pride is a profoundly disparate series. But its sincere commitment to exploring the full spectrum of LGBTQ+ life is sewn through it like a rainbow thread. The fact is, mainstream documentaries about queer history, though they are hardly ubiquitous, have tended to be one-sided affairs, mostly focusing on white gay men. Ironically in the act of historical rescue the lives of lesbians, bisexuals, and, especially, trans people of colour have been marginalised. Pride, at last, changes this. It is wonderful to see.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies