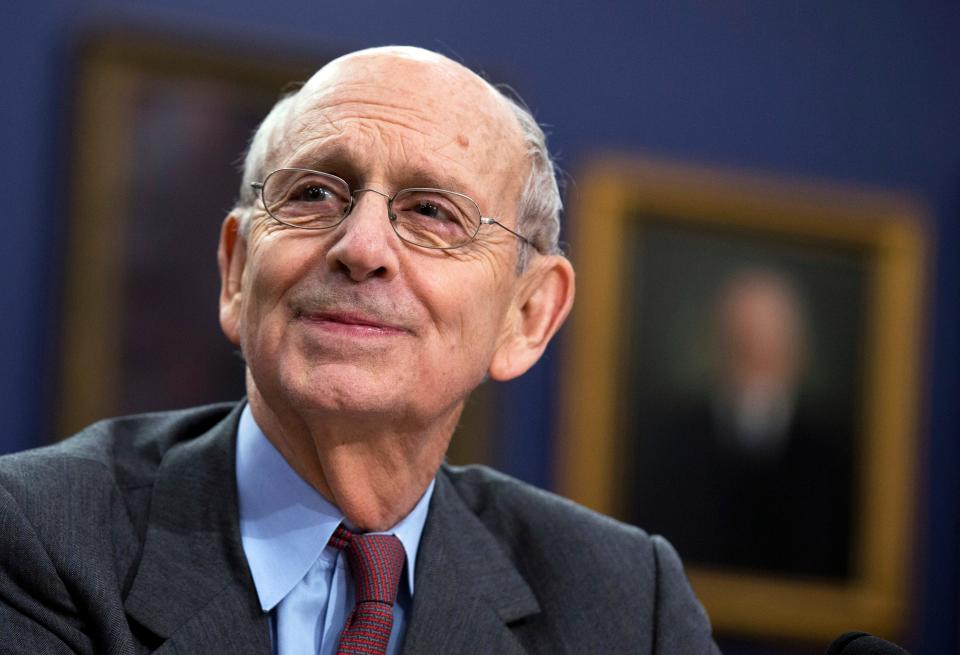

Pragmatist. Institutionalist. Optimist. How Justice Stephen Breyer changed the Supreme Court

WASHINGTON – Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, who plans to step down this year after nearly three decades on the high court, has made his mark as a pragmatist who helped forge compromises between liberals and conservatives at a time when the nation grew more polarized.

Less doctrinaire than Associate Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, Breyer nonetheless has been a reliable liberal vote on the court and an ardent opponent of originalism, the conservative approach of interpreting the Constitution based on its original meaning. Instead, Breyer believes in a "living" document that adapted to the times.

A philosophy major who clerked at the Supreme Court at the height of its push to expand civil rights under Chief Justice Earl Warren, Breyer is often described as an "optimist" and an "institutionalist" committed to the notion that the government is generally working in the best interest of the governed. He will end his tenure as the court has lurched to the right, with a majority distancing itself from those views.

"Justice Breyer wrote important opinions on topics ranging from abortion to the death penalty to school integration efforts, but I think his legacy will be defined as much by his big picture ideas about our system of government as his opinions in individual cases," said Brianne Gorod, chief counsel at Constitutional Accountability Center who clerked for Breyer in the 2008 term.

Breyer is a "unapologetic pragmatist," Kevin Russell, a former Breyer law clerk and frequent litigant at the court, told USA TODAY. "He always thought of the court as working in tandem with the other branches to ensure that we have a government that works well for real people in the real world."

Biden's chance to make his mark: Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer to step down

Affirmative action: Supreme Court to consider use of race in college admissions

As the court moved further to the right and conservatives embraced the idea of originalism espoused by the late Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, Breyer wrote a book in 2005 offering an alternative vision. In "Active Liberty,” he asserted judges should consider the framers' intentions as well as the practical consequences of their decisions. A prolific writer, he published "The Court and the World" in 2015, writing that foreign laws and treaties can guide judicial decisions in the United States.

A worldly lawyer, who married a member of the British aristocracy and can conduct interviews in fluent French, Breyer, 83, showed up frequently on the public speaking circuit to explain his line of work.

“I feel there’s a tremendous thirst for knowledge about the court,” he told USA TODAY in a 2015 interview. “My book is not just for lawyers and judges. It is for people interested in how their lives are being changed by what’s happening in today’s world.”

Breyer was President Bill Clinton's second appointment – his first was the late Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg – and enjoyed support from centrist Republicans and Democrats. He decried political portrayals of the court, dismissing the idea that justices decide cases based on the party of the president who nominated them.

'Think long and hard': Justice Breyer pushes back on 'court-packing'

"He has a real faith in government," said Risa Goluboff, dean of the University of Virginia law school who clerked for Breyer during the 2001 term. "That's where he sometimes departs from folks to his left and some folks to his right."

But Breyer in recent months has frequently found himself in dissent on a court where conservatives hold a 6-3 majority. Those divisions were put on display in a blockbuster case last year that undermined the Voting Rights Act and in decisions this year that allowed Texas' ban on abortions after six weeks of pregnancy to remain in place and to block President Joe Biden's vaccine-or-testing mandate for large employers.

Breyer is planning to step down by the end of the term this summer, a source with knowledge of his plans told USA TODAY on the condition of anonymity. Breyer, through the court, did not respond to a request for comment.

U.S. District Judge Vince Chhabria, a former Breyer clerk, said "pragmatist" fits in one sense but not inasmuch as it connotes someone who compromises principles.

"Justice Breyer is definitely not a pragmatist in that sense," Chhabria said. "He cares so deeply about these cases, and he works so hard to get the court to reach the right result. Whether he fails or succeeds, he really, really feels it. I’ve never met anyone who cared more about their work, and about our democracy, than Justice Breyer."

'A great teacher'

Professorial and convivial, Breyer often sprinkles his public speeches with references to history, foreign affairs and the classics. During a speech on international law at the Brookings Institution in 2014, he cited James Madison, Louis XIV, Cicero, the Magna Carta, Camus, Napoleon, the Nazis, Burkina Faso, Immanuel Kant and Alexander Hamilton.

Breyer’s flexible view of the law was illustrated in 2015, when he dissented in a case about lethal injection and said it was time to reconsider whether the death penalty itself is unconstitutional because of its slow, haphazard and sometimes mistaken application. It remains among Breyer's most widely cited dissents.

"Rather than try to patch up the death penalty's legal wounds one at a time, I would ask for full briefing on a more basic question: whether the death penalty violates the Constitution," Breyer said.

Texas death row case: Supreme Court wrestles with religious freedom in the execution chamber

Yet he has sided with the court’s conservatives in some major rulings – particularly involving Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable searches. Breyer upheld the ability of police to take DNA swabs from suspects after their arrest to enter into an unsolved crimes database, for instance. In a 1995 case, he voted with a 6-2 majority to uphold random drug tests for student athletes.

His deference to law enforcement extended to Congress as well. Breyer, an expert on administrative law who worked in the executive and legislative branches, was perhaps least inclined among his colleagues to strike down legislative actions.

On the other hand, he has been a critic of executive over-regulation.

Breyer sided with the court’s conservatives in a 2014 case upholding Michigan’s constitutional amendment banning affirmative action in university admissions. While approving of the use of racial preferences at colleges that allow it, Breyer said the decision can be left up to voters. He laid out a passionate dissent in 2007 when the court struck down an effort in Seattle to use race as one factor in deciding which schools students would attend to promote racial diversity.

"What of the hope and promise of Brown?" Breyer wrote, referencing the court's 1954 landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education. "In this court’s finest hour, Brown v. Board of Education challenged this history and helped to change it. ... The plurality’s position, I fear, would break that promise. This is a decision that the court and the nation will come to regret."

Biting dissents

Having served most of his tenure on a court that leaned right, Breyer long ago grew accustomed to small victories and became known for several important and eloquent dissents. One of his most noteworthy majority opinions in 2000 struck down Nebraska’s prohibition on late-term abortions. Three years later Congress banned the practice, and the court in 2007 upheld that law.

Despite the plaudits from the legal community, Breyer spent many years on the high court in relative obscurity with the public. He labored as the junior justice – responsible for taking notes and answering the door during the court’s private conferences – for 12 years before Associate Justice Samuel Alito was confirmed in 2006.

He was the least known of all nine members of the bench, recognized by just 2% of Americans in a 2018 poll conducted by C-SPAN. That poll also found that more than half of Americans couldn't name a single member of the Supreme Court.

During oral arguments, Breyer is often demonstrative, waving his arms for emphasis. His penchant for long, rhetorical questions often ended abruptly with statements like “Now, why am I wrong?" or "What do I do with that?" The exchanges bolstered the image of Breyer as an absent-minded, if brilliant professor.

Breyer’s life took him from one liberal bastion where he was born, San Francisco, to another where he spent the bulk of his career, Boston. He graduated from Stanford University and Harvard Law School, studying in between at Oxford University in England.

He spent much of his early career in Washington, working as a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, at the Justice Department and U.S. Sentencing Commission, and as counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee under Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass. There he earned a reputation for bipartisanship, helping to craft legislation deregulating the airline industry. He served briefly as a prosecutor on the Watergate Special Prosecution Force in 1973.

His reputation as a pragmatist helped advance his career. In 1980, just before leaving office, President Jimmy Carter named him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit in Boston. Republicans could have let the nomination languish following President Ronald Reagan’s election, but they allowed Breyer to be confirmed.

He served 14 years there, the last four as chief judge.

Along the way, Breyer, who is Jewish, married Joanna Hare, a member of the British aristocracy. They had three children, including a daughter who is an Episcopal priest.

Reading and riding

While working as a legal intern at an American law firm in Paris, Breyer became fluent in French, spending evenings reading Marcel Proust and jotting down words that were new to him on index cards. He recalled that process during a 2013 interview conducted entirely in French.

Breyer was a bike-riding enthusiast who had three major accidents – most recently in 2013, when he required reverse shoulder replacement surgery following a fall in the nation’s capital. When he first met with Clinton for a spot on the court in 1993 the thin and athletic judge was still recovering from a bad spill and was reportedly in pain and out of breath in the Oval Office.

The meeting did not go well, prompting Clinton to nominate Ginsburg instead.

An eternal optimist, he also faced his share of adversity: In 2012, he was robbed twice – on the Caribbean island of Nevis while vacationing with his wife, and at his Washington, D.C., home.

Those setbacks didn’t diminish Breyer’s joie de vivre. He continued his annual lunches with the nearly 40 law clerks who come and then go each year, as well as his off-the-record lunches with reporters.

Breyer, an Eagle Scout, insisted on hand signing postcards of congratulations to every Eagle Scout in the nation, a former clerk recalled. Breyer’s secretaries would entreat him to use an auto-pen for the job, but he scoffed at the idea and continued to sign.

"His sense of humanity is also something that is really core to who he is both as a person and as a judge," Goluboff said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Justice Stephen Breyer retires after nearly 30 years on Supreme Court

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies