'A post-retirement sweetener for military brass'? Pentagon defends mentor program amid fresh scrutiny

WASHINGTON – A lucrative Pentagon contracting program in which retired officers serve as "senior mentors" is under fresh scrutiny, despite reforms that required retired generals and admirals to disclose possible conflicts of interest.

The Pentagon employs about 80 retired generals and admirals, at around $90 an hour, to advise current commanders involved war games and other military activities. USA TODAY reviewed the financial disclosure forms of 77 senior mentors and found only a few working for defense contractors – a problem that had plagued the program when it was loosely regulated and conflicts of interest abounded.

But the revamped senior mentor program appears to be staffed almost entirely by men, the vast majority of them white, even as the Pentagon for several years has sought to develop leaders who reflect the diversity of the armed forces and the nation.

Another flashpoint: the conduct and hiring of two mentors. One of the retired officers, Lt. Gen. Gary Volesky, was suspended after mocking first lady Jill Biden on Twitter. A second mentor, Lt. Gen. David Huntoon, inappropriately used his aides to staff private charity events, feed a friend's cats and provide driver's lessons, according to a 2012 investigation by the Pentagon's watchdog.

Huntoon paid them with Starbucks gift cards. Admonished by the inspector general and the Army, he agreed to reimburse the employees more than $1,800.

“This is the crux of the problem with many in our military: They refuse to play by the rules and are allowed to get away with it,” said Rep. Jackie Speier, who chairs the House Armed Services Military Personnel subcommittee. “I expect to be briefed on the so-called mentor-mentee program. If it is a post-retirement sweetener for military brass, it not only offends me and the American taxpayer, it suggests a culture that continues the good ol’ boy network of feathering the nest of the elite officers no matter what."

More: Retired 3-star general suspended from Army contract after tweet that appeared to mock Jill Biden

The original senior mentor program had virtually disappeared after an investigation in 2009 by USA TODAY found that retired officers were being paid as much as $330 an hour to advise military services. Most of the mentors were also working for defense firms seeking to sell products to the Pentagon.

Because the retired officers were hired as contractors, few ethics rules applied. In some cases, mentors were paid by the military to run war games involving weapons systems made by their consulting clients.

Then-Defense Secretary Robert Gates and Congress intervened, requiring the mentors to be hired as government employees, subject to pay caps and required to file public financial disclosure forms. Virtually all of the mentors quit after those mandates took effect.

In 2011, the Pentagon inspector general found that only four of 194 senior mentors surveyed from 2010 continued in the program. The bottom line reasons that retired generals and admirals quit, according to the inspector general's report: a reluctance to disclose ties to defense contractors and the promise of greater riches in the private sector.

At U.S. Joint Forces Command, then commanded by Marine Gen. James Mattis, retired officers said they quit the senior mentors program because "conflicts of interest could limit a (mentor's) employment opportunities in the private sector," according to the inspector general's report.

Mattis, in an interview in 2009, dismissed the need for greater oversight of the program, citing the need to trust the retired senior officers. He acknowledged that mentors who worked for defense clients picked up information that benefits their private employers, but added that was the only way to ensure that top experts are teaching officers.

"If your concern is that we're exposing them to things that would allow them to have an advantage for their company, I doubt if that can be refuted," Mattis said. "I believe that's a reality. The only way to not have that would be to have either amateurs on their boards of directors, or amateurs in our (program)."

Imposing "an assumption of distrust and firewalls" could sour retired generals on the mentor program, Mattis said. "Ultimately, it comes down to trust."

But good-government advocates say the reforms were crucial.

"The reforms were intended to prevent this mentorship program from being a backdoor path for defense contractors to improperly influence Pentagon policy," said Danielle Brian, executive director of the Project on Government Oversight, a nonpartisan watchdog. "The only way to prevent corruption is through the transparency created by Congress a decade ago."

'Invaluable' perspective: Supporters defend current program

Since the IG's 2011 report, the program has rebounded and now boasts about 80 mentors.

Each of the services and the Joint Chiefs of Staff hire retired generals and admirals as "highly qualified experts," government employees with the rare skill and experience to advise senior officers on waging war. Ethics lawyers at the Pentagon review their finances and vouch for their eligibility to become senior mentors.

Army Maj. Gen. Mark Quantock, who retired as a top intelligence officer and is a mentor, said his colleagues did not join the program to make money. There's more to be made in private industry, he said, where he works for Babel Street, a data discovery and analytics software company.

"Having retired general officers providing perspective on what's worked and – more importantly – what hasn't worked to senior leadership is invaluable," said Quantock, who resigned from the mentor program in April.

The Army is the top employer of mentors, with 53. Many of them advise commanders in war games run through the Mission Command Training Center at Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas.

Some mentors have commanded at the corps level, where they led about 40,000 soldiers. They provide firsthand experience and insights to the Army's current commanding officers, said Myron Reineke, the top civilian official at the center.

Mentors allow the Army to "maximize training effectiveness, enhance unit readiness, and then implement lessons learned to ensure that these commanders the staffs are best prepared for future conflict," Reineke said.

There are only two women among the Army's 53 mentors, according to Cynthia Smith, an Army spokeswoman. Mentors are not required to disclose race or national origin, but Reineke said the mentors at Ft. Leavenworth are "overwhelmingly Caucasian."

"They are a reflection of the Army that they joined 30, 35 years ago," he said, referring to the decades it takes to ascend the ranks and become a general. "We strive to reflect what the diversity of the Army is, and again, that will continue to evolve over time."

The Army has struggled to diversify its ranks, particularly with Black officers. In 2020, Black people made up 22.7% of enlisted soldiers, 16.5% of warrant officers and 11% of officers on active duty.

Role models? Volesky and Huntoon's participation raises eyebrows

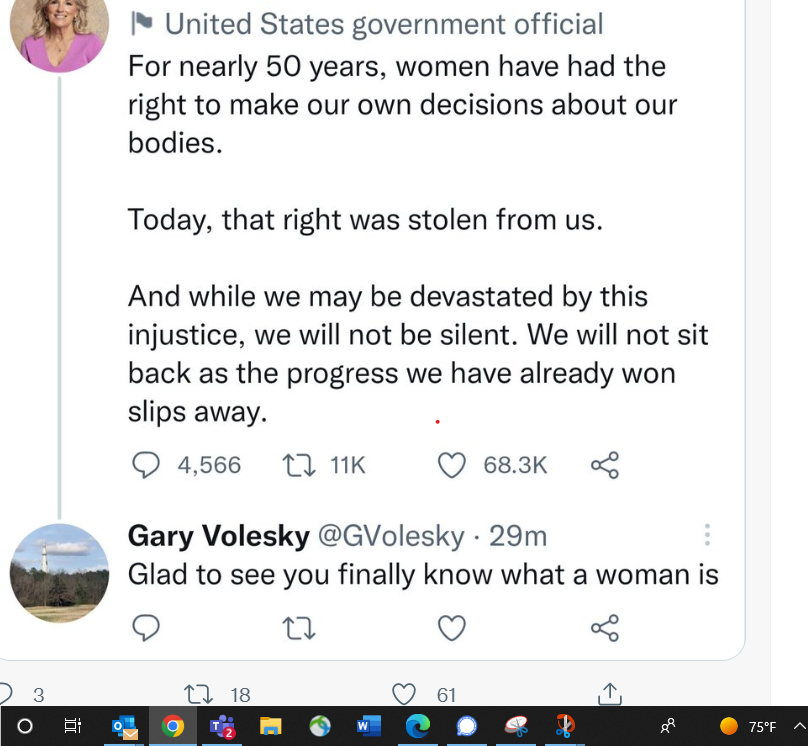

The Army suspended Volesky after he responded on Twitter to a post by first lady Jill Biden criticizing the Supreme Court's decision overturning the right to abortion.

"For nearly 50 years, women have had the right to make our own decisions about our bodies," Biden tweeted. "Today, that right was stolen."

Volesky tweeted in response: "Glad to see you finally know what a woman is."

Experts on military-civilian relations called his tweet a breach of decorum that strayed into partisan politics by an official on the payroll of the Pentagon, which is supposed to steer clear of such matters. His tweet was later deleted.

Huntoon's ethical lapse occurred more than a decade ago when he was superintendent at West Point. The Pentagon inspector general found Huntoon had improperly leaned on his staff to work at private events, including a "War College Ladies Luncheon" and "West Point Women's Club Viva! Las Vegas Night."

The report was released just prior to his retirement, and the Army announced that a letter was placed in his file admonishing Huntoon. Heavily redacted, the report notes that officers cannot use enlisted soldiers as "servants."

Huntoon, according to the report, accepted full responsibility for his actions.

Speier, the California Democrat, said Huntoon's actions are symptomatic of the military's inability to police its own even after Huntoon had admitted to abusing his "authority and office for personal gain," she said.

"Leadership has been reluctant to hold their own accountable who fall short of the high standards that Americans expect from the military," Speier said.

More:

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Pentagon's mentor program under fire for conduct, lack of diversity

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies