Poem of the week: Norfolk Sprung Thee … by Henry Howard

Norfolk Sprung Thee, Lambeth Holds Thee Dead

Norfolk sprung thee, Lambeth holds thee dead;

Clere, of the Count of Cleremont, thou hight!

Within the womb of Ormond’s race thou bred

And saw’st thy cousin crowned in thy sight.

Shelton for love, Surrey for lord thou chase;

(Aye, me! whilst life did last, that league was tender)

Tracing whose steps thou sawest Kelsal blaze,

Landrecy burnt, and battered Boulogne render.

At Montreuil gates, hopeless of all recure,

Thine Earl, half dead, gave in thy hand his will;

Which cause did thee this pining death procure,

Ere summers four times seven, thou coulds’t fulfil.

Ah! Clere! If love had booted care or cost,

Heaven had not won, nor earth so timely lost.

Glossary:

Thou hight – thou art called

Chase – did choose

League – bond

Kelsal – town in Scotland, burned by British forces in 1542

Landrecy – town in France, besieged by English and Spanish forces in 1543, not captured, but set alight by mortars

Render - surrender

Recure – rescue

Booted - valued

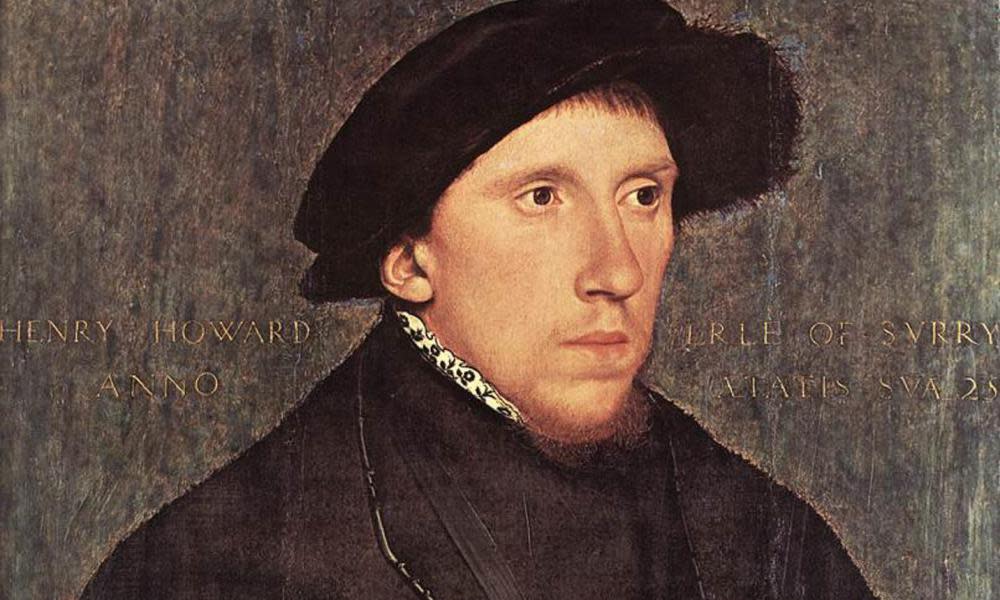

Poem of the week paid a previous visit to Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey (c 1517-1547) when we looked at the sonnet Brittle Beauty - formally inventive but autobiographically reticent, and so, rather ironically, well-named. This time, though still in sonnet land, we’re in a distinctly different part of the wood. In Norfolk Sprung Thee, Lambeth Holds Thee Dead, the young earl, writing in 1545, is mourning the recent death of his squire, Thomas Clere, a close friend and fellow poet. The form he has chosen is the soon-to-be-naturalised variant known as the English sonnet. It was to be Shakespeare’s own favoured structure, hence the alternative name, the Shakespearean sonnet.

Whereas the repetition demanded by the Italian sonnet – three quatrains using the same ABAB rhyme pattern – encourages the kind of verbal playfulness exhibited in Brittle Beauty, the English sonnet’s rhyme scheme helps Howard move this time in the opposite direction, towards plain speaking.

Because the rhyme-scheme in the English sonnet varies in each of the three quatrains (ABAB, CDCD, EFEF) it’s technically less of a challenge to writers in the rhyme-poor language of English. But the form exacts a cost. The “turn” after the 12th line can feel over-exposed, being reinforced by the final rhymed couplet. The poet needs a gift for aphorism equal to Shakespeare’s to make the denouement worth its rhetorical buildup. It needs to be snappy but not slick – and not so snappy that it seems to interrupt the previous discourse. It may be emotionally engaging, but the reader certainly doesn’t want to feel the poet has suddenly given up thinking in favour of a lovesick wallow. Howard’s final couplet succeeds admirably in all respects. It resonates with, and beyond, the thought it caps.

The success of Norfolk Sprung Thee … lies in the poet’s having picked a form to match complexity of feeling. It’s both a love poem and an epitaph – and an epitaph more than an elegy. The opening trochaic line gives it the sombre decisiveness of a funeral march. The writer, unencumbered by poetic flourishes, takes pains to present key facts of the addressee’s genealogy, going on to list some of the battles the two men shared. Finally, in the third quatrain, the “story” behind Clere’s death is revealed. This the source of the poem’s emotional intensity.

Thomas Clere was the youngest son of Sir Robert Clere, from Ormesby in Norfolk, and a descendant of Clere of Cleremont in Normandy (in the poem. “Cleremont” needs to be pronounced with three syllables). As the title starkly proclaims, Thomas Clere was buried in Lambeth, London (in the churchyard of St Mary’s, to be precise) some distance from the Norfolk home that “sprung” him, ie gave birth to him. He had died as the result of being wounded while saving Howard’s life. The earl had led an attack on the besieged French city of Montreuil, but the attack failed for want of reinforcements. Clere had saved his friend’s life, but the wound was to be the cause of a slow (“pining”) death.

Related: Poem of the week: Brittle Beauty by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey

Howard’s brief account of Clere’s ancestry includes references to the “cousin crowned in thy sight” (Henry VIII’s second wife, Anne Boleyn, was Clere’s first cousin) and to “Shelton”, Mary Shelton to whom Clere was engaged. The emphasis is increasing on the “league”, the bond between the two men. Perhaps a hint of competition is signalled between Mary Shelton, chosen by Clere “for love” and the poet, who has been chosen (merely?) “for lord”. There may be a suggestion of more-than-brotherly emotion in the word “tender” in the exclamatory line six, and the term “pining” in line 11, often associated with the death of an abandoned or separated lover.

Emotion visibly breaks through the sonnet’s public address in those lines, but not only there. “Thine Earl, half dead, gave in thy hand his will” is probably not a reference to the handing over of the protagonist’s “last will and testament” but the submission of his body to another’s care. His hand is taken by Clere, and he submits. The term “half dead” suggests physical and mental prostration. It’s a familiar expression in modern English, and it marks one of those moments that allow the contemporary reader to bridge the centuries, forget the deep differences between attitudes then and now towards war, imperialism and aristocratic hierarchies. As the poem unfolds, Henry Howard seems to sense his loss more keenly, and the couplet is both confessional and dignified. Henry himself had only a short time left. Two years after writing this lament, he would be executed for supposed treason. He died at the age of 30, the self-sacrificing Thomas Clere at 28.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies