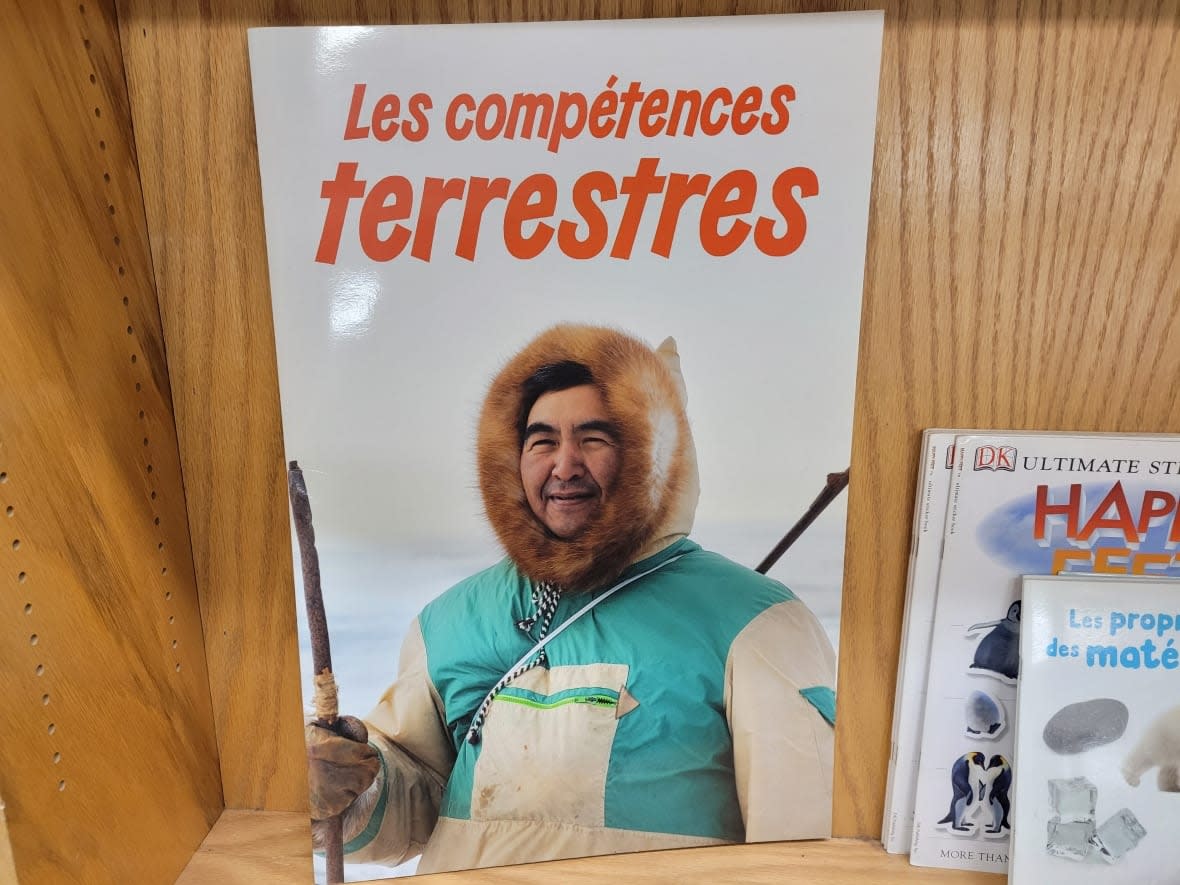

How a photo of an Igloolik man ended up on the cover of a book without his consent

Teman Avingaq first saw the book with his picture on the cover when his daughter stumbled on a copy a few years ago.

Avingaq is smiling in the photo, wearing a fur-trimmed parka. It was taken during a narwhal hunt near Arctic Bay. But the Igloolik man had no idea the book — titled Les compétences terrestres — even existed.

He'd consented at the time to having a photographer take his picture, but hadn't consented to the photo being sold online to publishers looking for images for magazines and books.

He didn't often think about the book, but it started bothering him after people he didn't know began recognizing him.

He thought about suing the publisher, Inhabit Media, but didn't think that would go anywhere.

"I just want a fair deal, and maybe a bit more for the misappropriation of [my photo]," he said.

How did it happen?

Avingaq's image is on the front of Les compétences terrestres, or, Land Skills. There are French, English and Inuktitut versions of the book.

Inhabit Media cofounder Louise Flaherty told CBC the Inuit-owned company uses consent forms when it puts a call out for photos. But when the company can't find a photographer, it goes online to find images.

"An example is, if I was looking for an Inuk woman with an amauti, I would type that in and hundreds of photos would show up," she explained.

The company would then purchase the photo from the photographer, taking it on faith that the photographer got the subject to sign a consent form.

"When that purchase [of Avingaq's image] was made, we as the business assumed that a consent form had been signed," she said.

"This became a learning curve for us, because we are few in number as Inuit — there's only so many of us and in most cases we know each other. The learning curve that I had was, OK, we cannot assume a consent form was signed if a photo was purchased off the internet."

Flaherty suggests other Inuit should explore what photos of themselves might exist online so they know what's out there and whether their images have been used as Avingaq's has.

"By fluke, when I looked up 'Inuit women' for example, some [photos] of my friends and acquaintances are also for sale on the Internet. And it makes me wonder if a consent form had been signed," she said.

"So if you're an Inuk and curious about whether your identity or image is being sold on the Internet, just explore, because people might be making money off the Internet without your consent."

What now?

In most of Canada, people don't own the rights to their image.

Avingaq spoke with a civil lawyer about his options.

"She said I can only ask for $70, plus maybe 10 per cent royalties from whatever money they made," Avingaq said. The purchase price of the photo was $70.

Flaherty said Inhabit Media doesn't pay royalties for the purchase of photos — only to authors.

She said anyone who finds themselves in Avingaq's situation should contact the publisher to get recognition in the book.

As for Inhabit Media, she said it's clear they need to start making sure the photos they purchase include consent from the subject — and says getting consent is a lesson photographers should take away from this, too.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies