Philip Larkin’s profound and beautiful poetry sent me back to the classroom

It must be possible to believe that a curriculum should not be preserved for all eternity in aspic – that some measure of change can only be a good thing – and yet still to grieve on hearing the news that OCR, one of the three main exam boards, has removed work by Thomas Hardy, John Keats, Philip Larkin and Wilfred Owen from its syllabus.

Such mournfulness seems natural to me, born as it is as much of what we love as of where we might stand in the culture wars. If the young don’t yet have their favourite verses, the rest of us wander around with certain lines engraved forever on our hearts, the only truly lovely remnants we may have of our long-ago school days.

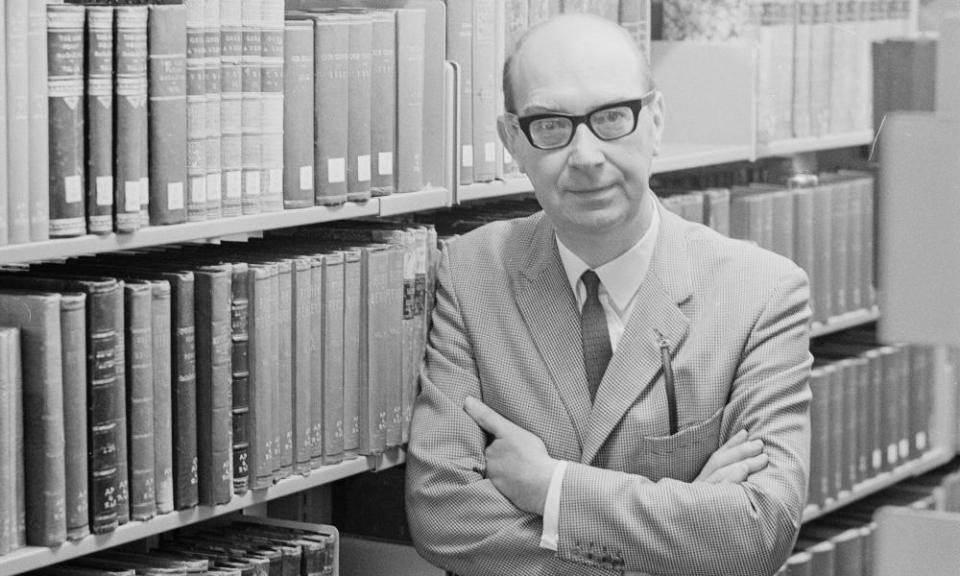

Larkin has always been my man and I hate the thought that others might not find him as I did. At 16, I was an educational disaster. Teachers’ strikes had made it easy to wag it and quite soon I was pretty much a full-time truant, a state of affairs that endured for more than a year. Only when I happened to open The Whitsun Weddings did some spark of interest finally stir deep inside the lazy, truculent refusenik I’d become. Larkin’s poems – this is hardly news – are extraordinarily beautiful, extremely profound and, above all, amazingly easy to read. He was, I’ve always felt, my unlikely saviour, his existential despair serving somehow to rouse me from my Nescafé and Neighbours stupor; his famous and ineffably lovely arrow-shower refreshing parts of the teenage me no other poet could possibly reach.

Treasures lost

At the Courtauld Gallery to see its Edvard Munch exhibition, I wandered into a side room and found a heart-stopping collection of photographs of Iraqi Kurdistan. Taken in the 1940s by Anthony Kersting (1916-2008), they depict many buildings that have since been destroyed by IS, as well as the people – the Yazidis, in particular – for whom they were sacred. What treasure! And yet, how melancholic. I stared for a long time at the disappeared Mosque of Nebi Yunis near the site of ancient Nineveh, which was blown up in 2014. Having replaced an Assyrian church, it was reputed not only to be the burial place of Jonah, but also of the whale that swallowed him, of which a large tooth remained by way of evidence. The Courtauld holds 42,000 prints by Kersting, images it’s in the process of digitising thanks to a volunteer army that has so far donated 32,000 hours of its members’ free time.

In search of Scargill

Everyone I know is watching James Graham’s series Sherwood, a drama set in a Nottinghamshire village still scarred by the divisions of the miners’ strike. But if we’re gripped by its plot, we’re also spooked by its timing. Last week, it was almost as if Graham had conjured a ghost, episode four having been broadcast on the same day that Arthur Scargill, the former leader of the National Union of Mineworkers, was seen joining a picket line in support of the rail strike.

Thanks to my Sheffield roots – in the early 1980s, the NUM built a huge HQ in the city, its central section designed to resemble a pithead; it was known locally as King Arthur’s Castle – I will never stop being fascinated by Scargill, nor writing to him asking for an interview (he never replies). Following his reappearance, I wasted an age on the NUM’s eerily quaint website, where I read, mouth wide open, of Low Hall in Scalby, near Whitby: a 31-bedroom house that comes with a library and crown green bowling and which is otherwise known as the Yorkshire Area Miners Holiday Home.

• Rachel Cooke is an Observer journalist

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies