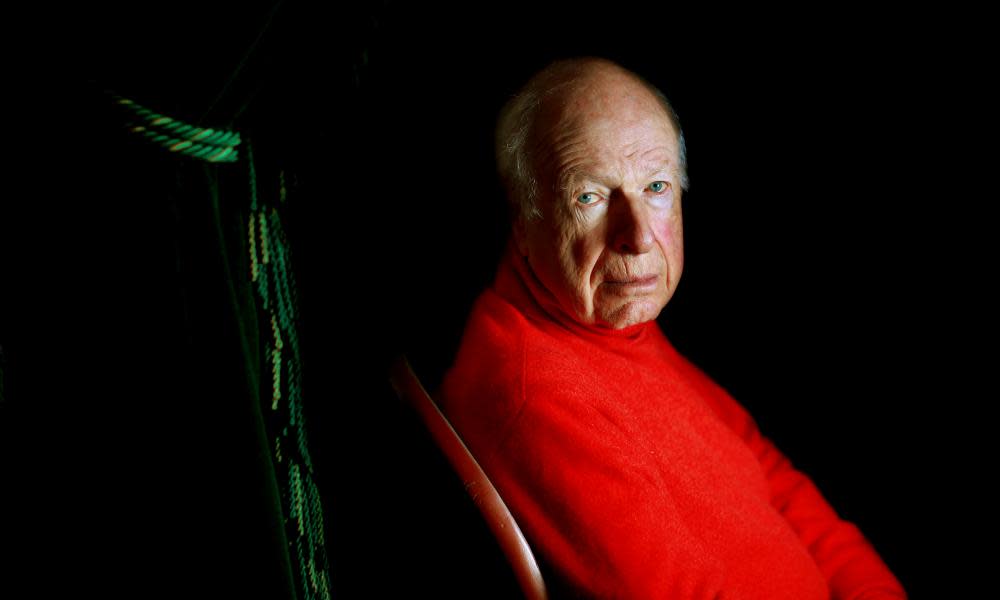

Peter Brook obituary

Peter Brook, one of the most original and influential theatre directors of the 20th century, who has died aged 97, was a questioner all his life. He disliked being called a guru, because the term implied lazy pupils and received solutions. He did not consider himself an artist, or an ideologue; but he was certainly a teacher, and for many an exemplar. He explored the interior world of the self and the nature of reality in dramas of every description – Shakespeare, opera, Asian epic and invented language – on stages and spaces all over the Earth. Literally the earth on many occasions: in a thyme-scented quarry south of Avignon in France, in the villages of west Africa and the deserts of Iran.

His own guide into that interior world of reality was the early 20th-century mystic George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, and his chosen medium of transmission the ancient temple of entertainment, civic healing and personal truthfulness: the theatre. How the pilgrimage and the medium came together, at a time when theatre was commonly seen to be retreating on all fronts, was the story of Brook’s life. No one did more to take drama out of the conventional auditorium and kindle it wherever performers and spectators could meet to share an “empty space” – the title of his most influential book, published in 1968.

Brook was both shaman and showman, a seductive mixture of spirituality, worldliness and mischief. He was held in great affection in the profession and one of many Brook stories has him falling on a copy of Variety on the plains of Persepolis to check his Broadway takings from the previous week. To those who asked him how to recover the theatre’s lost audience he had one favourite answer: “Cheap seats.”

It would be pompous to see any contradiction in this, for Brook’s spiritual strength was rooted in an unblinking perception of the material world. He worked brilliantly for 15 years in the commercial theatre of London, Paris and New York before seeking time for research from the culture of public funding. Classics, new plays, musicals, operas, scandals, flops and hits: the breadth of his early training taught Brook never to bore audiences if you were bored yourself. His 1958 production of the musical Irma la Douce ran for more than 1,500 performances, and every kind of theatregoer adored it. The Little Hut (1950), a French farce thought very saucy at the time, ran almost as long. “I’ve never believed in a single truth,” he wrote in The Shifting Point (1988), a collection of articles, interviews and anecdotes. Changing one’s mind, he insisted, was the only way to arrive at a firm decision.

Born in London, Peter was the son of loving, gifted, but quarrelsome Russian Jewish parents, Ida (nee Jansen) and Simon Brook, whose pharmaceutical company developed the laxative Brooklax. Educated at Westminster school and Gresham’s school, in Norfolk, he grew up with an equal passion for cinema and theatre. Ill health kept him out of the army, and at Magdalen College in wartime Oxford he began to make films with friends. After being nearly sent down for watching rushes in mixed company out of hours, and ejected from Wardour Street for shooting a Rinso ad in the style of Citizen Kane, he had no choice but to opt for the proscenium arch of the London West End stage.

Looking back from the heights of his well-funded, hard-won Parnassus in Paris nearly half a century later, Brook was funny, but generous, about this essential English apprenticeship. “The theatre world to which I was now drawn,” he wrote in the memoir Threads of Time (1998), “was dominated by men with fastidiously draped muslin curtains at their windows.”

Impresarios such as Barry Jackson and Binkie Beaumont allowed him to cut his teeth on plays including George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman (1945), Romeo and Juliet (1947) and Jean Anouilh’s Ring Round the Moon (a huge success with Paul Scofield and Margaret Rutherford, in 1950). When he and his beautiful young wife, Natasha Parry, kept house in London for much of the 1950s, they too lived in a tiny, charming, overfurnished home and received fastidiously draped friends from behind muslin curtains.

The young Brook directed for Beaumont in the West End, and for Jackson in Birmingham and Stratford. Quite how he became Covent Garden’s first director of productions at the age of 22 has never been fully explained, except that he wrote asking for a job and David Webster, the canny Liverpudlian who ran the house, was a talent spotter and liked to shake things up a bit. But only a bit. In 1949, a “scandalous” Salome, designed by Salvador Dalí, confirmed Brook as the bad boy of the business, and got him the sack the next morning.

Like other great theatre directors – Peter Stein and Ingmar Bergman come to mind – Brook believed that the actor was the beginning and end of the play and that “total theatre” could be created by the resources of the human body alone. It was the director’s job to find the source of the actors’ energy, bring their performing and offstage selves into harmony, and make sure that this wholeness informed every move they made and every word they spoke (and then to make it look easy).

His first actor-companion in the lifelong pursuit of quality and truthfulness was not Laurence Olivier – whose speed of thought Brook believed to be an illusion, protected by a mask – but John Gielgud, in productions of Measure for Measure (1950), Venice Preserved (1953), The Tempest (1957) and Seneca’s Oedipus (1968). Gielgud’s apparent indecisiveness concealed a tenacious fine-tuning much like Brook’s own. Scofield succeeded him, with a West End season of Hamlet (1955), TS Eliot’s Family Reunion (1956) and Graham Greene’s Power and the Glory (1956). Later, in 1962, Scofield would be Brook’s magnificent, sardonic Lear – rarely equalled, and never surpassed, since.

At his best, Brook liberated actors. Without his acute sensitivity to each actor’s energy and impulse, it is unlikely that either the introspective Scofield or the angular Glenda Jackson would have become the stars they did. Later, he would speak of the instinctive, “invisible” acting perfected by African and American performers at his International Centre for Theatre Research in Paris, but he could also free space for the biggest West End stars to achieve invisibility of a more artful kind. When he directed Christopher Fry’s The Dark Is Light Enough (1954), a preposterous Habsburg melodrama was redeemed by the translucence of Dame Edith Evans, who died eight times a week with breathtaking invisibility from the depths of a very large chair.

Even Olivier dropped his mask and gave one of his greatest performances on the single occasion he worked in the theatre with Brook. Those who saw him in Titus Andronicus (Stratford, 1955), when Brook imposed a fierce, ritualised discipline on one of Shakespeare’s most violent plays, would remember his grief for the rest of their lives. Brook was the first theatre director to see that the horrors of history itself had caught up with Titus, and gave it a production that foreshadowed the nightmares he was to address in the next decade.

Throughout his career he made films, latterly of his theatre work, and, as late as The Lord of the Flies (1963), he still wanted to be a movie director. He used 83 miles of film for William Golding’s fable of lost innocence, and took two years to edit it. Perhaps it is not surprising that the result, despite fine camerawork and a schoolboy cast, lacks spontaneity. More fun, if virtually forgotten, is a paintbox-bright studio version of The Beggar’s Opera (1952), for Herbert Wilcox, designed by Georges Wakhévitch with a cast led by Olivier, Stanley Holloway, Dorothy Tutin and Athene Seyler – a colour postcard from Binkie’s British theatre.

Posterity may decide that his best is the wonderful Moderato Cantabile (1960), a windswept winter’s tale of uncommitted adultery in a shabby, sad port on the Gironde. Based on a novel by Marguerite Duras, this is Brook’s engagement with the French nouvelle vague, spellbindingly told through two of its most luminous icons – Jeanne Moreau and Jean-Paul Belmondo. Brook was a superb storyteller in the theatre, but only in Moderato Cantabile does he find a comparable narrative assurance for the cinema – lyrical, shocking, cantabile indeed.

Nineteen sixty-two was the turning point, after which, for Brook, theatre would always take precedence. He came to believe that cinema had acquired a spurious reputation for “reality”, when in fact its images are frozen in time. Theatre always asserted itself in the present. It was more real, more risky, dangerous and disturbing. This was the year when his Theatre of Cruelty group, based on the writings of Antonin Artaud and set up with Charles Marowitz at Peter Hall’s new Royal Shakespeare Company, inspired the uncompromisingly harsh King Lear, the first of three historic RSC Brook productions that examined the compulsiveness of human cruelty and help, to this day, to define cultural London in the 60s.

Lear was followed by Marat/Sade (1964), Peter Weiss’s virtuoso take on the terror in revolutionary France, and US (1966), a company-devised show in reaction to the Vietnam war. Marat/Sade, in which the unknown Glenda Jackson burst on the world as the inspired rustic assassin Charlotte Corday, proposed the sanity of madness in the aftermath of unreason’s tenure of power; the production was adapted for a film version in 1967, with many of the original cast. US rudely broke the silence beneath which the British government condoned the escalation of conflict in Vietnam. It was the most overtly political work Brook ever did; anticipating, as Hall has pointed out, the confrontations of 1968. Although sometimes mocked for its naivety, it asked a lot of embarrassing questions, marked a rare moment of global actuality in British theatre, and made clear to Brook one theatrical road down which he would not go.

Lear, Marat/Sade and US established the Brook legend in Britain. Success became triumph with the radical and witty RSC A Midsummer Night’s Dream of 1970, in which the wood near Athens became a bare white box, Puck walked on stilts, Oberon commanded the action from a swing and Titania rose imperiously on a scarlet feather boa. Inspired partly by Jerome Robbins’s ballet masterpiece, Dances at a Gathering, admired in the west for its clarity and in the Soviet bloc for its subversiveness, “Brook’s Dream” became even more famous than Bottom’s, ran on Broadway, and marked his departure from both the anglophone theatre and the proscenium stage.

In 1964, he had directed a production of Genet’s The Screens at the RSC’s Donmar Warehouse in Covent Garden, then literally a warehouse, and it launched the adventure that was to inform the rest of his career. He had begun the charge through the proscenium arch and into the auditorium so that audiences and actors could share the same “field of life”. He was not the only director to take theatre out of the theatres, in Britain or in Europe, but he was the most effective. The charge became a stampede, and by the end of the century at least two generations of younger theatregoers had grown up for whom the proscenium arch itself was an alienating presence - the exception, not the norm.

In The Empty Space, adapted from his four Granada lectures of 1968, Brook declared that you can take any space and make it a bare stage – “You don’t need red curtains, spotlights and tip-up seats” – and he divided theatre into four kinds: the deadly, in which nothing happens; the rough, which is real but lacks vision or head; the holy, in which narrative, performance, spectators and place come together; and the immediate, which changes all the time.

In hindsight, these lectures read like Brook’s farewell to Britain. There was no money – and no will – to fund a Peter Brook company whose prime purpose was not performance but experiment and research. French cultural policies were both more cosmopolitan and more open to risk-investment in the individual artist. Over the previous decade, Brook had directed the French premieres of several key plays of the time so, in 1970, when French faith was backed by funding from the French government and from the Ford, Robert Anderson and Gulbenkian foundations, Brook moved to Paris. He was 45, in mid-career, and at the height of his powers.

There, he founded the International Centre of Theatre Research (ICTR). Its vision was a form of theatre comprehensible to all, dealing with universal emotions. The first actors were recruited from France, Britain, America, Romania, Poland, Italy, Mali, Nigeria, India and Morocco. Brook chose – in his own words – “people who had been marked by life, but not too drastically”. The aim was to see if there was a “form of theatre which acts like music”, and appeals to audiences of many kinds.

From 1971 to 1973 the ICTR troupe travelled, played and improvised on carpets in deserts, bush, immigrant hostels, tribal villages and refugee camps across the developing world. The experience was a refining one, but also instructive. “We went wherever there was nothing to rely on,” wrote Brook, “no security, no starting point. In this way we were able to investigate the infinite number of factors that help or hinder performance. We could learn about … distances, seating arrangements, about what works better indoors and what is gained by playing outside … about parts of the body, the place of music, the weight of the world, of a syllable, of a hand or foot, all of which years later would feed our work when, inevitably, we returned to a theatre, tickets and a paying audience.”

The birth of the ICTR coincided with a brief flowering of the international arts in late-imperial Iran. One of the earliest and most extraordinary experiments for Brook’s company of actors with no common language was Orghast, a drama of archetypes staged in 1971 for the Shiraz festival in the ruins of Persepolis and on the bare plain of tombs where the dead kings of Persia lie. They spoke three archaic languages – Greek, Latin and ritual Persian Avesta – and a fourth, “Orghast”, invented by Ted Hughes. The archetypes included blind kings, rebellious servants, quarrelling fathers and sons. Extracts from, or allusions to, Aeschylus (Prometheus Bound, The Persians), Calderón (Life Is a Dream) and Shakespeare (The Tempest) deepened the epic synthesis.

In Paris, Brook was kept above the swift stream of French cultural politics by his general manager, Micheline Rozan. In 1974, he and Rozan found the centre a permanent home for research and performance, in the derelict, mosque-like Bouffes du Nord, an old variety house near the Gare du Nord. Brook levelled the stage to the stalls to form a large, rough acting floor; the audience usually sat round the back of the stalls and upstairs, but the configuration would vary. This was a place rescued from obsolescence and, like the actors, “marked by life”. The pipes of defunct services were laid bare, the belle époque decor was partly left in place, partly “distressed” in great sweeps of terracotta and ochre paint by Wakhévitch, Brook’s designer at Covent Garden a quarter of a century before. The ICTR is still there.

In this enfolding space – primed with expectation, haunted by old songs and dead gags, layered with memory like the ruins of Pompeii – Brook staged a rep that ran from devised African pieces (Les Ik, 1975; The Conference of the Birds, 1980) to Timon of Athens, The Cherry Orchard and Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. About two-thirds of the way through rehearsals, each show was taken before a demanding audience, usually schoolchildren on their own ground. In 1979 the centre went to Afghanistan to film Gurdjieff’s early memoir Meetings with Remarkable Men. The result now looks both sophisticated and naive, but declares two of Brook’s most firmly held beliefs. Knowledge and learning are not the same thing. Curiosity, not explanation, is the motor of human existence.

The ICTR was never designed to produce a masterpiece, but in 1985, it did. All the research, travelling, absorbing and discarding bore glorious fruit in Jean-Claude Carrière’s trilogy based on the Indian epic cycle of the Mahabharata. It was as though Brook’s whole journey had led to this spectacle of celebration, sensuality, fighting, healing and love. It enlightened the last years of a century over which the dark age of Kali had lengthened its shadow of destruction.

The Mahabharata married east and west with the elements of earth, water and (most thrillingly) fire; the adventures of gods and mortals rang with echoes of Homer, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Shakespeare and Wagner. Arjuna, the great archer, spoke for all heroes in all epics when he stood between two armies on the eve of Armageddon and cried, “Why should we fight?” Both he and the blind king Dhritarashtra had their roots in Brooks’s Titus, Lear and Vietnam. The Mahabharata even promised immortality as a gilt-edged cert, as the dead reassembled blissfully in the final moments at a place of feasting, music and resolution. A nine-hour French-language production in three parts, it was performed by an outstanding ensemble of actors, and when you left, you walked off the ground.

Some critics – in India and America – dismissed it as “orientalist”, but audiences disagreed and wherever it played, it was both communal and transformative. As a theatre critic, I saw the cycle four times in three years – in the Rhone quarry outside Avignon where it began; at the Bouffes du Nord; in Brooklyn, where, translated into English, it drew le tout Manhattan; and finally in Glasgow, when it enabled the conversion of the former Museum of Transport into the Tramway arts space. In Brooklyn, as in Glasgow, The Mahabharata inspired an exceptional new venue: the abandoned Majestic vaudeville house became New York’s Bouffes du Nord. In cities across Europe – Frankfurt, Hamburg, Zurich, Brussels, Barcelona and Copenhagen – similar “found” spaces for theatre owed their existence to Brook.

Watching the Brook phenomenon at work in France – where he was French theatre’s star of stars – was to observe the rites of a working marriage that always remained a love affair. “Bravo Brook!” cried a voice in ringing tones from the back of the house as he took his seat just before the overture to Don Giovanni at Aix (1998), and Brook sat down demurely as though he had not heard a thing. “The French press is naturally analytical,” he explained to an English critic at lunch on another occasion, having sat like a wise bird before a group of Parisian scribblers who smothered their questions with a lot of guff about the circle of religion and the spiral of dialectic in The Mahabharata. The only sign that his sweet patience might be under any kind of strain was when his eyes gazed over their heads to the back stalls and turned an even more intimidating shade of pale blue. (“Twinkling ice-picks,” thought Kenneth Tynan, who first met Brook at Oxford.) One remembered that, by his own account, boredom was his greatest enemy.

Brook’s most original and moving work in the 90s was L’Homme Qui (The Man Who, 1993). Based on the neurological cases in Oliver Sacks’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat, this was, Brook insisted, not a play but a piece of theatrical research into the real fabric of living experience. He described it as the most collaborative work he had ever done, involving five years of experiment and research with Sacks (initially), a dramaturg, a composer, four actors, and patients and doctors in Paris.

The result was an odyssey of inner adventures that exemplified Sacks’s own view that the broken-minded are the new heroes, standing on the frontier of the modern age. A quartet of superb performers – David Bennent, Yoshi Oida, Bruce Myers and Sotigui Kouyaté – invested the experiment with a humanity further enriched by Brook’s use of video cameras and screens.

Some of the quartet continued into Qui Est Là (1995), a meditation on Hamlet – the title strips the question-mark from the first sentence of the play – and on acting, directing and theatre in the 20th century. Scenes of the Prince, Ghost and Player King were stitched in and out of writings by the men who created modern theatre and influenced all those who came after them: Artaud, Brecht, Stanislavsky, Meyerhold and Gordon Craig, plus the Noh master Zeami. The result was a little dry, but memorable for the transcending simplicity of performers who had, by then, been working with Brook since the early years of the ICTR – above all, the tall Malian actor Kouyaté.

Kouyaté exemplified the principle behind much of Brook’s later work: complex thoughts must always be expressed in the simplest form. When it worked, the search for simplicity revealed the core of truth. In La Tragédie de Carmen (1981), Brook had cut Bizet’s sprawling opera comique to the terse shape of a Greek tragedy, with no chorus and only a small band. Nothing diminished the speed of tragic intensity with which the tale unspooled.

When the search for simplicity failed, either the performance had not succeeded in shedding the old conventions sufficiently or its impact was lessened by what looked like under-casting in the metropolitan venues where Brook’s late work mostly played. When Brook returned to the RSC in 1978 to direct Antony and Cleopatra with Jackson and Alan Howard, he did not carry his (by then) highly mannered stars with him, nor did he take all his singers on the journey through Don Giovanni at Aix-en-Provence in 1998; although much admired in the French press, this production seemed to some perversely asexual. Similarly, A Magic Flute (2011) discarded far more than it retained. The magic was still there, but the mystery had gone.

No Brook project was ever “definitively” completed, and during the first two decades of the new century he revisited and refined, often in intimate form, earlier sources and inspirations: Shakespeare (a successful, substantially cut Hamlet with Adrian Lester, 2000); Russian literature (Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, 2005); Chekhov’s correspondence with the actress who became his wife (Ta Main Dans la Mienne, 2003); Indian epic (Battlefield, 2015); the revolutionary theatre of Vsevolod Meyerhold (Why?, 2019) and, most rewardingly, the conflicting sacred worlds of modern Africa.

Tierno Bokar (2004, adapted in Britain as 11 and 12 in 2010) laid out the painful pathways between violence, forgiveness and faith. Its provenance was typically Brookian: a timeless drama illuminating today, played by actors from four continents, based on the life of the Koranic sufi Bokar by the Malian ethnographer Amadou Hampâté Bâ, and turned into a play by Brook’s closest collaborator of the last 40 years, Marie-Hélène Estienne. The embattled Bokar walked to his death as to a great feast – another echo of The Mahabharata.

Brook’s epic masterpiece was never seen in London – neither money nor will were enough to fund the conversion of a venue – and when his later work was shown here it never visited for long. His dazzling British career ended nearly half a century ago, but is no less significant for the effect it had on audiences, actors and theatre companies, at the time and for many years after. Fluent late writings on Shakespeare (The Quality of Mercy, 2013) and on music and sound (Playing By Ear, 2019) will further ensure that his particular wisdom and plain common sense are cherished. He never stopped working.

Public challenges to his reputation were rare, but seismic tremors were felt at the Hay festival in 2002 when David Hare contrasted the overtly political theatre of John Osborne with Brook’s “universal hippie babbling, which presents nothing but fright of commitment”. In the ensuing private correspondence, which explored the intransigently different virtues of French and British culture, the two men eventually found more in common than otherwise. But Brook pointed out that, without ever announcing the fact, the ICTR had, from the start, tackled one major political issue of the modern age head on: racism. Slowly and patiently he had created a true theatre of the world.

Brook was appointed CBE in 1965, and Companion of Honour in 1998. He received honorary doctorates from Oxford, Birmingham and Strathclyde universities. In 1973 he received the Hamburg Shakespeare prize, and in 2008 became the first winner of Norway’s International Ibsen prize. In France he was a commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and a commander of the Légion d’honneur. He received the Padma Shri from India in 2021.

Natasha died in 2015. He is survived by their children, Irina and Simon.

• Peter Stephen Paul Brook, theatre director, born 21 March 1925; died 2 July 2022

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies