Peter Brook’s legacy is everywhere in today’s theatre

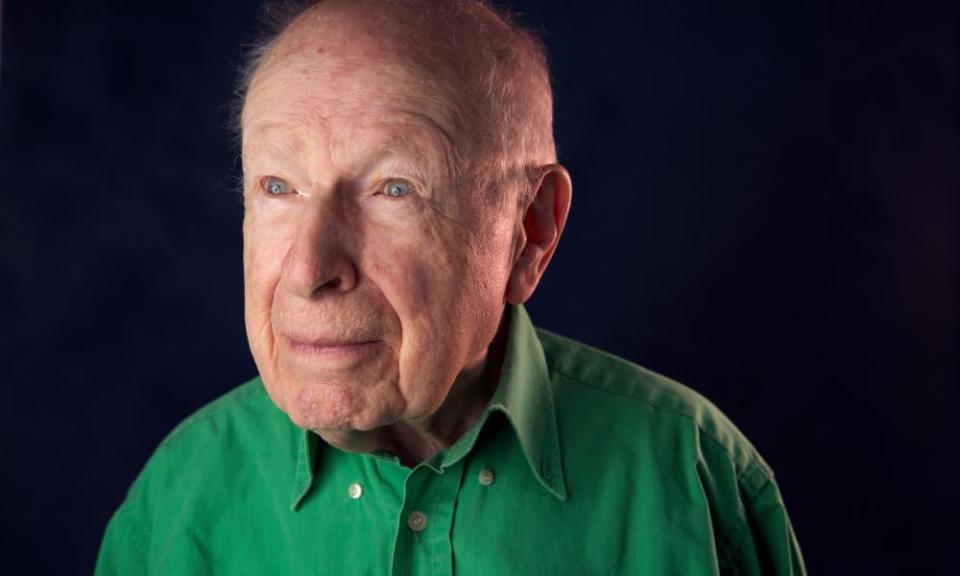

Never meet your heroes, the saying goes. When I first encountered Peter Brook, in 2010, he was not so much hero as legend: guru, shaman, magus, maestro. He was frail – tiny, too, shuffling into the theatre in enormous, thick-soled white shoes. But the moment he trained his famous ice-water-blue gaze on you, it was clear his mind was made of steel.

Reputation does funny things to people; especially in theatre, an artform given to myth-making, where stories about famous shows you didn’t happen to see expand with the telling. I’m decades too young, for instance, to have witnessed seen any of Brook’s early or middle-period work, the sprawling spectacles of La Conférence des Oiseaux or The Mahabharata. The director I encountered was the late minimalist, the polisher of parable-like pieces that gleamed like pebbles beneath the surface of a river. Often they were cryptic, sometimes downright puzzling. But Brook’s ability to conjure a gleaming theatrical image – collaborating since the mid-1970s with his trusted lieutenant, Marie-Hélène Estienne – was unparalleled. I recall the actor William Nadylam in The Suit whisking a handkerchief from a pocket and turning it into a tablecloth, voilà, just like that. Then there was an evening of Beckett shorts with Marcello Magni, Khalifa Natour and Kathryn Hunter. I’m able not just to picture it in my mind but to almost replay it, so piercing was its clarity.

Brook was also – and this is rarer than one would think – an intensely musical director. His cut-to-the-quick Magic Flute with piano and a cast of nine, which I saw in 2011, caught the gossamer lightness of Mozart’s writing and exuded impish joie de vivre. Brook displayed a similarly restless creativity that was fully Mozartian, as well as the skill of switching from ebullience to grave seriousness in a flash. Brook also had the peculiar showman’s art that made it all seem artless. When I interviewed Estienne in 2015, she told me his actors – usually in their 30s and 40s – found the demands of endless rehearsal exhausting, but Brook himself never did.

Battlefield (2015), based on The Mahabharata, flickered in focus for me: at times thrillingly clear, at times gnomic to the point of obscurity. The Prisoner, which came to London in 2018, was purportedly based on an encounter from Brook’s own life four decades before, it felt both out of time and out of joint, particularly in its portrayal of themes such as incestuous rape and colonialism. But for anyone to maintain a 70-year-plus career in the theatre, let alone one that changed directions as often as Brook’s did, is astonishing. Brook seemed to have hung on to his youth partly via his involvement with younger theatre-makers. As well as being a generous collaborator, he welcomed a steady stream of acolytes to tthe Bouffes du Nord and in his later years became a visiting elder statesman at London’s Young Vic. Dog-eared copies of his book The Empty Space may no longer be a must-have accessory for wannabe directors (and thank goodness for that, Brook might have said), but his influence is all around: in the hectic inventiveness of Complicité, the stripped-back essentialism of Cheek by Jowl, as well as in the styles of theatre-makers as varied as Marianne Elliott, Robert Icke, Emma Rice and Ivo van Hove.

Related: 'I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage': 10 of the best Peter Brook quotes

Watch companies such as 1927 or Frantic Assembly, or the boundary and border-crossing experimentalism of directors such as Yaël Farber, Kwame Kwei-Armah and Tim Supple, and you are seeing Brook’s influence, often from work done more than a generation ago. His most important legacy might be making mainstream drama properly multicultural. His projects with artists from across the globe, of many cultural backgrounds and ethnicities, have their critics, but they were genuinely pioneering. They helped change the face – and faces – of theatre for good, and infuse inward-facing British theatre with a sense of continental elan.

One of my last encounters with Brook came in 2015, at the Bouffes’. The cast had taken their bows, the audience begun to scatter. I was up in the gods when I spotted Brook far below. He’d been hanging back in the shadows; I was told later that he wasn’t meant to be in that night. But he couldn’t resist popping by to see how the show was getting on. I watched him being guided gently through the proscenium arch to give the actors notes. A few soft words of advice and he’d be gone.

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies