Paul Gambaccini: ‘I’d be happy to see the BBC go’

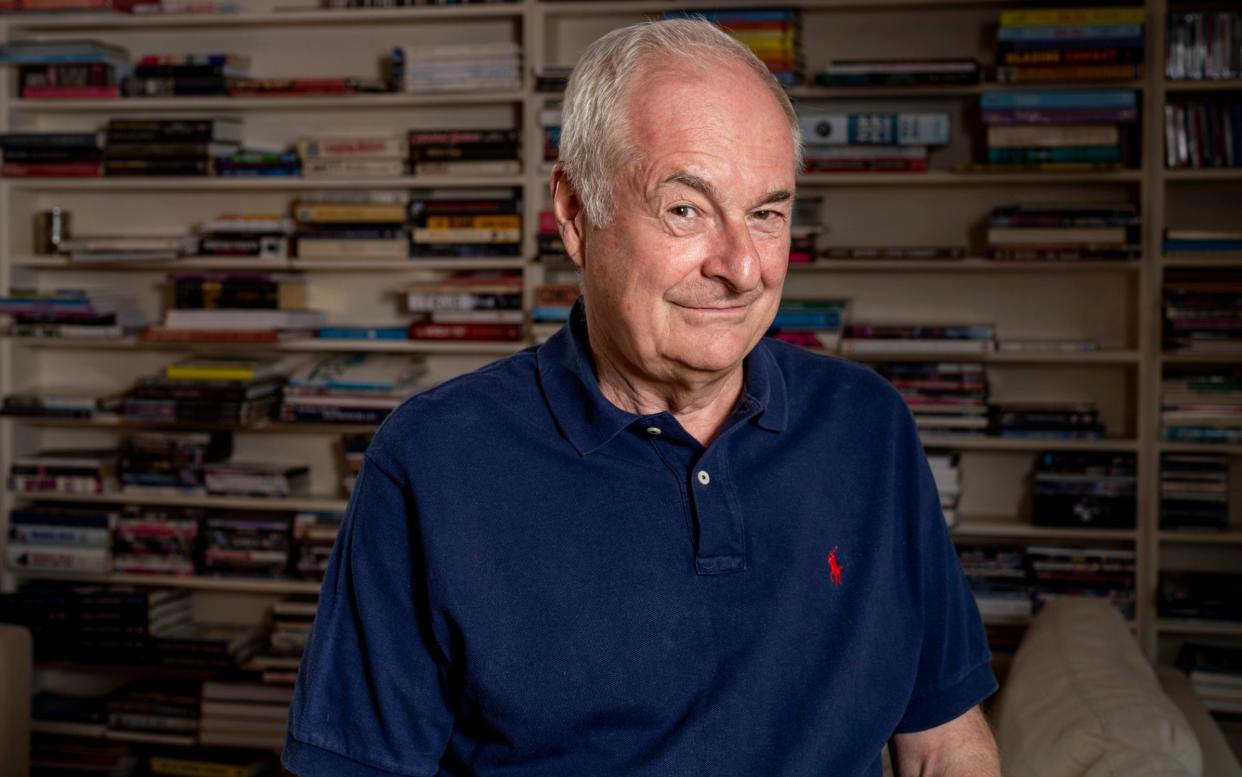

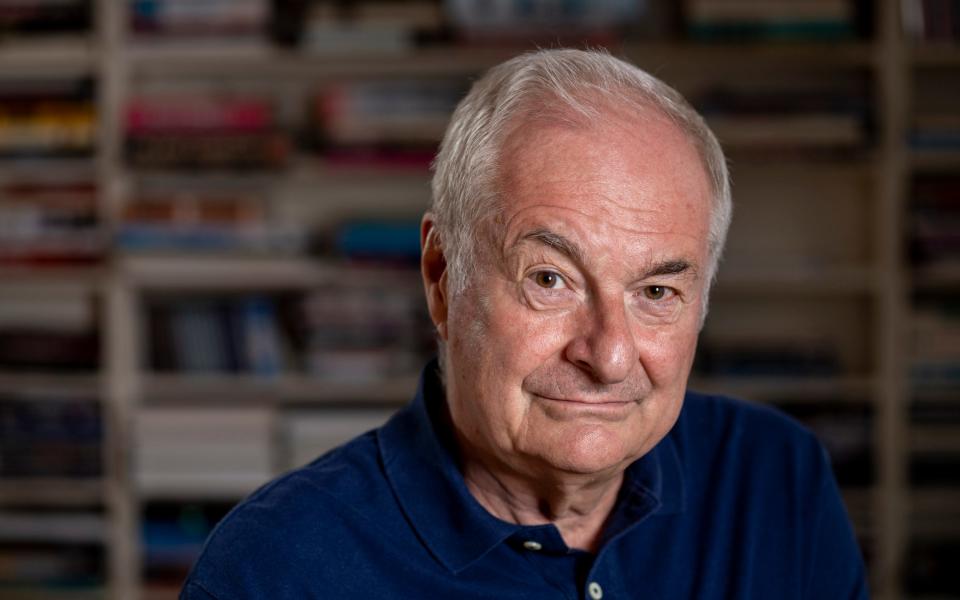

Paul Gambaccini is wound up. The 73-year-old disc jockey – aka The Great Gambo, aka The Professor of Pop – has a lot on his plate.

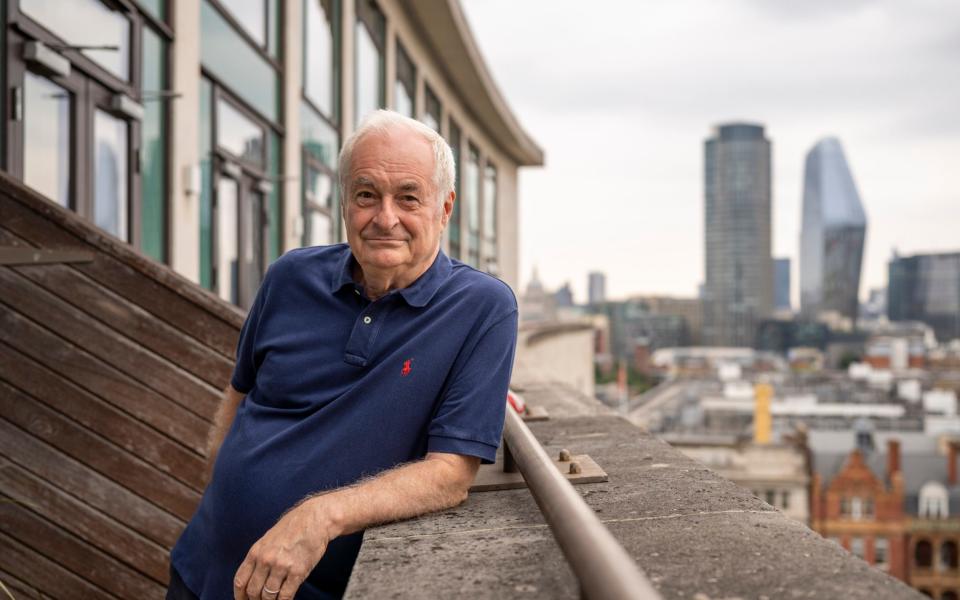

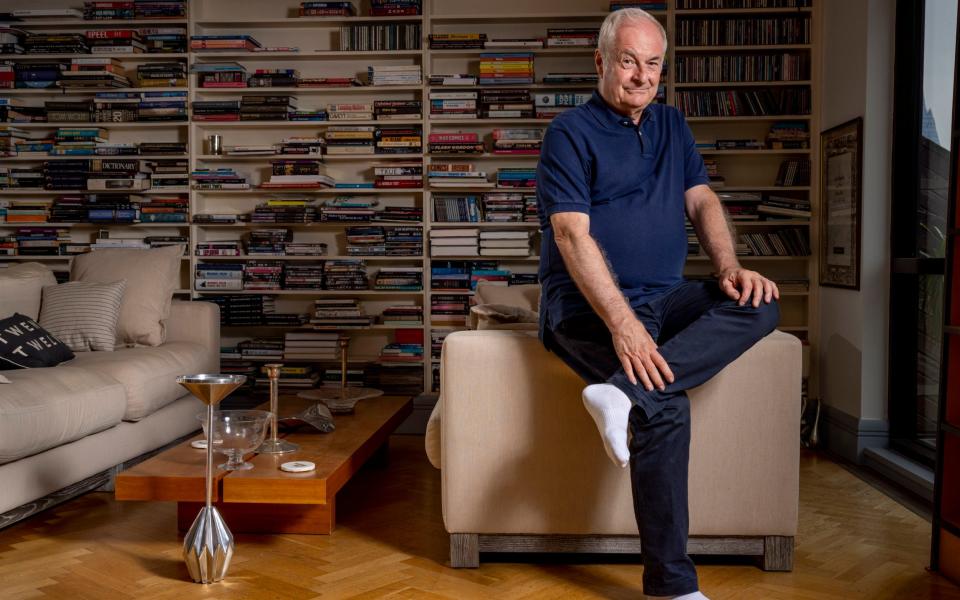

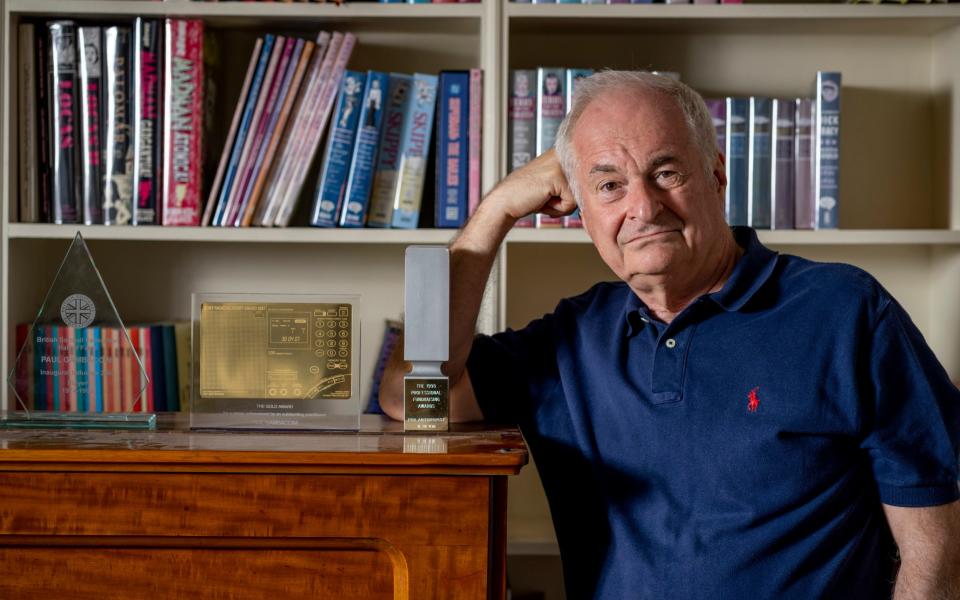

There is, for starters, moving house. Two decades’ accumulation of records, CDs, award statuettes and books (including several volumes of his own highly successful Guinness Book of British Hit Singles) are in the process of being taken down from their carefully ordered shelves in the roof-top riverside apartment on London’s South Bank that he shares with his actor husband, Christopher Sherwood.

Then there are his regular gigs on Saturdays on Radio 2’s Pick of the Pops (which has 2.2 million regular listeners) as well as quizmaster on Radio 4’s Counterpoint. And, most stressfully, next week he will return to an unhappy and scarring chapter in his life when he appears as one of three household names (alongside his professional peers Sir Cliff Richard and DJ Neil Fox) in a new Channel 4 documentary, The Accused: National Treasures on Trial.

Broadcast to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the revelation of the full extent of the crimes of serial sex abuser Jimmy Savile, the programme chronicles how, in the wake of Savile, they all faced potentially career-ending accusations of preying on young fans which were splashed all across the media, before eventually being cleared of any wrong-doing.

It inevitably brings up unhappy memories just at a point when Gambaccini is trying to “move on” from the past by relocating nearby to a house with a garden, and explains why the man sitting opposite me at his kitchen table is not his usual on-air self – jovial, laid back and effortlessly articulate.

In his blue polo shirt and matching trousers, he retains the agelessness that has kept him on the mainstream schedules when other DJs of his generation have faded away to BBC local stations or “golden oldies” radio. But the strain is there too in his face from the start as his 37-year-old husband – they met in 2010 on Facebook, married two years later, and recently celebrated their 10th anniversary – makes tea and tries to lighten the mood by chatting about his latest acting jobs before heading off upstairs.

At the heart of much of what weighs on Gambaccini’s mind is a preoccupation with the state of what seems (apart from with Sherwood) to be the most significant and enduring relationship in his life: a love affair with the BBC that began when John Peel gave him his first slot on Radio 1, kept bringing him “home” to the corporation even after flirtations with breakfast TV channel TV-AM in the 1980s and later Capital and Classic FM, but turned sour in November 2013 when BBC bosses took him off air after police arrested him in this flat in a dawn raid after two men accused him of sexually abusing them in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Gambaccini insisted from the outset that the accusations were “ludicrously false” since there was not a shred of evidence to back them up. It took the Metropolitan Police’s Operation Yewtree 11 long months to reach a similar conclusion.

During that time he was on police bail, cooped up in his flat (the new documentary includes, for the first time, video diaries he made at the time that show the depths of his despair at his treatment). He was forbidden even from going bowling with his 15-year-old nephew, and feared that he could no longer live in a country he had made his own since arriving here as a 21-year-old to take up a prestigious Rhodes scholarship at Oxford at the same time as Bill Clinton.

He had initially hoped that he could keep working after his arrest, but he believes BBC top brass made a “public relations decision” rather than doing the right thing and investigating whether the accusations against him were substantial enough to outweigh the corporation’s accumulated knowledge over four decades of just what sort of person he was. They did not stand by their man, as he had stood by them.

“They refused to hold true to the BBC’s historical moral responsibility,” he says, “yet it still claims that it deserves a licence fee.” Not for the only time in our discussion, he moves effortlessly from the personal and particular to make a wider judgement on everything the corporation does. In the process, the gentle, wry smile fades, and the tone in his familiar voice hardens. There is evidently a lot of anger in him.

Like many who go through a painful and sudden divorce, Gambaccini wants to go into forensic, almost obsessional detail about how the BBC has betrayed his trust. “The things I believed in most,” he says, “have become the things that I believe in the least.”

It seems too obvious to point out that he is still working for the BBC. He returned shortly to the airwaves after the Crown Prosecution Service decided not to charge him.

“Our central relationship as broadcasters,” he explains, justifying his decision, “is with our audience. It is not with our managers.” The distinction may be lost on some, but given how he feels, surely it would have been better to swap to a different platform. He seems not to register the suggestion, so – when I can get a word in edgeways – I try another tack.

The BBC has, of late, been actively policing what its big names say in public, causing the likes of Andrew Marr, Emily Maitlis and others to seek new outlets to nurture their relationship with audiences. Yet, curiously, it puts up without protest when Gambaccini bad-mouths it repeatedly.

His most recent outburst last September, a bad-tempered, shouty exchange about the BBC with a very calm Victoria Derbyshire, went viral. In it he accused the corporation of being “on the side of wrongdoers”, giving “free rein” to fantasists to accuse well-known names of paedophilia, and participating in a “witch hunt”. He even singled out the then head of news, Fran Unsworth, and challenged her to a public debate in which he would “dissect her like a frog, without ether”.

“Christopher still can’t bear to watch that,” he confides when I repeat his words back to him. He appears slightly – but only slightly – shamefaced. “I have moved on.” That is not the impression he gives.

It was the only one of his flare-ups that prompted a warning shot across his bows. “I received a visit from a BBC executive three days later. They sat on that sofa there and told me they didn’t mind me talking about the management in the Lord Hall era [Tony Hall, director-general when Gambaccini was taken off air] as long as I didn’t mention serving people at the BBC.”

An odd line to take, but a mild enough rebuke in the circumstances. Might this softly-softly approach just be a sign of collective guilt about how they treated him back in 2013?

“I think they are keeping themselves safe. It is to stop me writing the book. Can you imagine?”

In 2015, he published Love, Paul Gambaccini: My Years Under Yewtree, a hastily-put-together account of how the police operation had left his life in limbo. His friend Elton John – it was his interview with the singer in 1973 that first opened Radio 1’s door to Gambaccini – described this volume of memoir as one that “more than puts the record straight”.

So what else is there to say – or for the BBC to fear? “I haven’t said as much as there is to say. This subject goes so deep and dark it could fill your whole paper.” He is sounding like a conspiracy theorist and it is unclear whether he is actually writing something more at the moment. What is plain is deep and dark is the hurt that is eating away at him – and causing him, uncharacteristically, to lash out.

Is there anything he still values in the BBC that he once loved so passionately? “I prize the great international BBC correspondents. That’s my BBC. But the domestic news department is a travesty.”

Here again the personal becomes the general, his views inevitably shaped by the way that department in particular treated Cliff Richard. The two were friends already when Yewtree blew up, but have supported each other throughout their shared trauma of false accusation. In July 2018, Richard won his High Court case against the BBC and was awarded £210,000 in damages for their news coverage of his case.

Assuming that there must be some residual affection left in Gambaccini for the corporation he has now spent almost 50 years of his life with, I ask if he wants it to survive in the face of the current threat to its licence fee and even its charter.

“No,” he replies adamantly.

He’d really be happy to see it go? “Yes. They refused to give us justice. To me when the current Director General refused to engage with me on this topic, I just thought…”

He stops and puts his head in his hands. Earlier he has described how, when he gets angry, “the red ball at the end of the thermometer is threatening to explode”. His anger is in many ways understandable. In the Channel 4 documentary, some of those involved in Operation Yewtree dismiss the suffering of those it arrested, bailed and never found evidence to charge as “collateral damage”, a price worth paying because they nailed a minority of those captured in their net (including Gary Glitter and Rolf Harris, who were convicted and jailed).

To be described as “collateral damage” must stick in the craw when your hitherto happy life has been completely upended. Gambaccini had met Sherwood in 2010 and the couple married in 2012. An album of photographs of the couple, compiled to mark their 10th wedding anniversary, lies on the table between us.

Yet just a year after they had tied the knot, the police came knocking on their door. “This house has been sullied by memories of the presence in it of police officers.” It is, Gambaccini says, part of the reason they are moving – out and on.

It is not that he doesn’t realise he has a problem with the anger inside him. And if it had escaped his notice, then his husband is on his case. In the documentary, Sherwood does an impression of Gambaccini getting angry.

Yet he hasn’t sought professional help, the DJ says. “During the 70s I had analysis because of what I will call a difficult family background.” Raised as one of three sons in the Bronx by Italian-American parents, he gives no details of what the difficulties were. In an interview, when asked when he came out, he replied he had never been in, and was one of the first well-known broadcasters to speak openly about being gay.

It is his Italian grandma, he remembers, who was the most vivid character in those early years on the other side of the Atlantic. She was deeply Catholic and “spent a fortune” posting letters to world leaders accusing them of turning their back on God and signing herself “the Peacemaker of Christ”. You begin to understand why he stayed on in Britain.

“I learned a lot from analysis,” he reflects, “including how to analyse myself.” For now, then, he is trying to sort himself out.

It begs the question of why agree to be part of the new documentary, with all that goes with it. Part of the reason is practical, he says. The director, Charlie Russell, is the grandson of another old friend, the novelist Beryl Bainbridge. Russell was the one who made the video diaries during Gambaccini’s months on police bail. “So I trust him.”

Yet if he really wants to move on, then keeping quiet might be a better way. He shakes his head. “Peace,” he points out, “is not the same as acceptance”.

To illustrate his point, he recalls an occasion in 1986 when his mother (neither of his parents lived to see him arrested) was over on a visit to London. “I recall it very clearly. We were crossing Shaftesbury Avenue and she turned to me and said, ‘I would hate to be the person to wrong you. You never forget’.”

Was she right about him? “Unless I am provoked, I find now that I can go for a couple of days without thinking about what happened. But there is also a difference between forgiving and forgetting. I’m more into forgetting. No one has asked for my forgiveness so for me it is not a relevant concept.”

Among those he struggles either to forgive or forget are Keir Starmer, who was in his final days as Director of Public Prosecutions in the same month that Gambaccini’s arrest took place. “It was Starmer’s dictum as DPP that with these allegations of sexual abuse police should ‘believe every accuser’. With that, he inverted the basic principle of British law – innocent until proven guilty. It became guilty until proven innocent.”

His long-time support of Labour – he even held celebrity fundraisers in this flat, attended by then leader Ed Miliband shortly before his arrest – is a thing of the past. As soon as he was arrested, the leadership “dropped me like a hot potato”. The prospect of Starmer as Prime Minister “fills me with gloom”.

He describes Bernard Hogan-Howe, Metropolitan Police Commissioner at the time of his arrest, as “the villain of my life” but manages – just about – to turn an encounter with Hogan-Howe’s boss into an anecdote not a rant. As Mayor of London in 2014, Boris Johnson was also the city’s Police and Crime Commissioner.

Gambaccini had been invited to dinner by an old friend, the Tory former cabinet minister Andrew Mitchell, shortly after his police bail ended. Johnson and his second wife, the QC Marina Wheeler, were the other guests. “But what was your case about again?” the mayor turned and asked him.

Whether it was ignorance or evasion, Gambaccini wasn’t impressed (but didn’t, he adds, blow up). “I have since the day I was arrested been in a country where the most powerful figures have been the ones who participated in my persecution or permitted it.”

It is that all-pervading sense of being let down again. That said, holding the powerful to account is a cause many would agree with. And he has had some successes, notably in persuading then Home Secretary Theresa May in 2014 to introduce a 28-day limit on police bail.

“She is one of my heroes,” he says. It is good to know he still has some.

Not so the current Home Secretary, Priti Patel. He met her at a House of Lords event where he and Cliff Richard were promoting their campaign that all those arrested by police should remain anonymous until charged. “She listened, but instead of supporting us she asked me if I would denounce the BBC. She showed no interest in the administration of justice.”

Patel may now be thinking he has done her bidding, even if it wasn’t his intention. It is another of the complications of combining being a much-loved DJ with outspoken campaigning. But not one, it appears, sufficient to stop him trying.

The fight will go on, less angrily, from his new home nearby – “a house with a garden”, he reports cheerfully. He just can’t let it go. “No man,” he insists, “can acquiesce in his own destruction.”

The Accused: National Treasures on Trial, Wednesday 24th August, 9pm, Channel 4 & All 4

Yahoo Movies

Yahoo Movies